For a while you could hear the words “broken metabolism” everywhere in the online space. Whether it should’ve been termed “Metabolic Damage” (broken metabolism) or “Metabolic Adaptation” (downregulated metabolism), wasn’t clear and had yet to be decided – thankfully, we did begin to change the termanology.

Because people were scared, if we’re being honest. Everyone was saying that years of dieting had “broke” their metabolism and damaged their hormones to an extent that they were now unable to lose weight.

It almost seemed like a ‘Hail Mary’ to anybody who could not understand why they were struggling to lose weight, even though they believed to be in a caloric deficit.

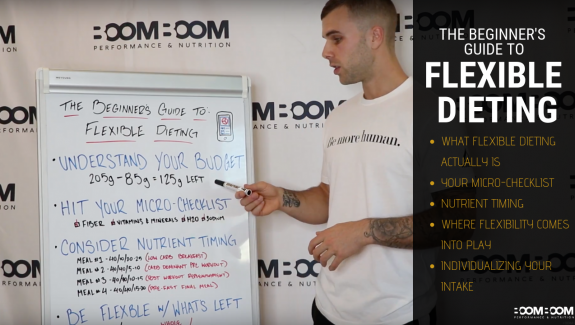

First of all let me say that many people who think they are in a caloric deficit – are not. Most of us underestimate our caloric intake (not logging occasional licks and bites or eating too many processed foods that don’t necessarily have accurate food labels) and overestimate our activity level.

Secondly, the concept of a “broken metabolism” has been debunked as a myth many times over and it has been shown that frequent or sustained periods in a caloric deficit don’t cause your metabolism to “break”, but rather cause it to down-regulate or adapt.

“Broken” would mean it is a permanent adaptation, “down-regulated” means it can be restored.

This is the good news.

The bad news is still that dieting affects your metabolism and if not done in a planned and structured way, a diet might well leave you gaining more fat back afterwards than what you started with…Not ideal!

So knowing why your body adapts to a deficit in the first place, how it tries its absolute best to conserve energy when dieting, how your hormones are affected and what other physical adaptations that leaves you with can help you through the dieting process and more importantly can help you plan out your diet – and your diet after the diet!

So WHY does our metabolism down regulate through dieting?

Think of it from an evolutionary standpoint. Your body is receiving signals that there is a shortage of food (less food/calories going in than before). It understands this as a potential famine and so it wants to protect itself from starvation (little does your body know the next McDonalds is just around the corner…).

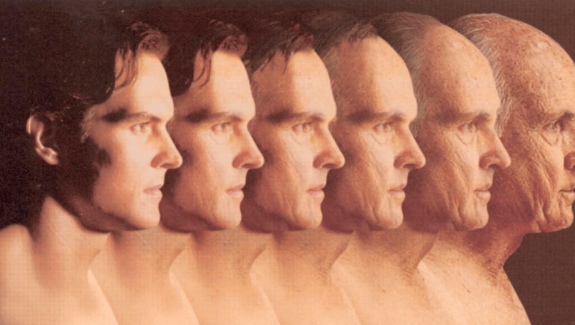

So from an evolutionary perspective this is super helpful, because it means in the future you can survive on less food. For us nowadays, not so convenient, because it means our maintenance calories are lower after a diet than they were before. And if at some point after your diet you would want to lose fat again, you would have to lower your calories even more than you did the first time to see any change at all…But you can only go so low with your calories and then what? Add an extra 3 sessions of cardio? Not sustainable or optimal for longevity…

Thankfully there are strategies you can implement to help you minimise “the damage” (or more like the adaptation in this case) a caloric deficit has left on your body.

We will go over these strategies shortly, but first let’s explore HOW your body actually adapts to the calorie deficit you’re putting it through.

It’s likely that all of our bodily functions are affected in some way by a caloric deficit, but here are some of the main ones:

The body focuses on spending less energy

→ Our mitochondria, the cell’s power houses become MORE EFFICIENT at producing energy from food. “More efficient” usually sounds like a good thing, but when it comes to metabolism we actually want to be inefficient at converting energy from food (fast metabolism), which means we need to eat more to get the same amount of energy as a person with an “efficient”/slow metabolism.

→ Reduced energy availability during training, meaning performance declines or at the very best stays the same.

→ Building or maintaining lean body mass is no longer a focus for the body. LBM is the most “expensive” tissue to maintain for the body, it requires a lot of energy. The body decides it does not need to make this a priority right now – giving the energy to organs, the brain and just generally the vital functions is much more important. This is why building muscle mass is next to impossible during a severe or chronic deficit. Most of us are lucky to maintain muscle mass during a diet.

→ Cognitive function goes down. Less food also means less fuel for the brain. More brain fog, less energy for skill acquisition and execution, less remembering…

→ NEAT, non-exercise activity thermogenesis, drops. Yes, we can try to keep it in check as best as possible by making sure we get the same amount of steps every day etc, but due to the fact that involuntary movements such as fidgeting, sitting up right etc. are all reduced, the overall NEAT is going to be reduced, like it or not.

→ Due to the fact that we are eating a smaller amount of food, the TEF, thermic effect of food, is also reduced (proportionally this is a relatively small contributor).

→ Basal metabolic rate (BMR) is reduced. This is probably the biggest influencer in reducing overall energy output (makes up about 70% of our total daily energy expenditure!!). Less metabolically active tissue, which means lower BMR.

Even when we keep our Exercise Activity Thermogenesis high (for example by increasing training frequency or volume and adding cardio here and there), it is very difficult to make up for the other 90% of your down regulated TDEE.

It’s also important to note that this down-regulation is usually much higher than what we expect, looking at the fat loss or size of our caloric deficit. Adding on to this, these down-regulations usually stay in effect even AFTER the diet. This down-regulation is called “adaptive thermogenesis” and explains to a large extent why we hit weight loss plateaus and why gaining the weight back after the diet is so easy.

“Energy deficits and extremely low levels of body fat present the body with a significant physiological challenge. It has been well documented that weight loss and energy restriction results in a number of homeostatic metabolic adaptations aimed at decreasing energy expenditure, improving metabolic efficiency, and increasing cues for energy intake.” (1)

[Learn More About Periodizing Your Diet, To Avoid Weight Regain, Right Here]

The body wants to prevent starvation in the future

All the processes named above essentially help prevent future starvation, but here are some additional adaptations that may occur:

→ Hormonal adaptations:

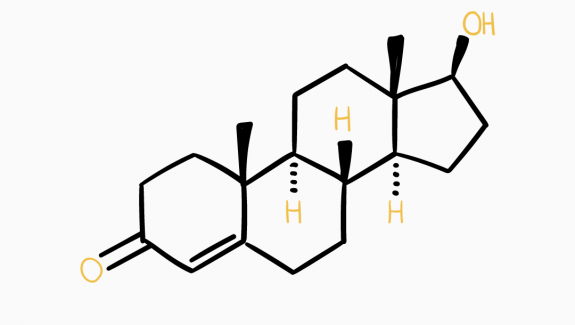

Losing fat means fat cells shrink and with that less leptin is secreted- one of the body’s main hormones regulating hunger and metabolic rate. Ghrelin on the other side, the body’s main hunger stimulating hormone, is increased which makes it more and more difficult to feel satisfied as your diet goes on… The list goes on and on as basically every hormone in our body is affected through dieting in one way or another (for example cortisol goes up, sex hormones go down) and this unfortunately also includes our thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), which also plays part in lowering metabolic rate.

→ Adaptations after the diet:

Research also clearly shows that not only do we become more efficient using energy DURING a diet, but even after a diet our bodies are more likely to store excess energy as fat than it was before. Adding on to this, big refeeds after a diet (aka binges, cheat meals, cheat days etc) may actually increase the production of small fat cells (again, think evolution, and preventing the danger of death by starvation…) which also could be part of the reason why it is easy to gain EVEN MORE weight back AFTER the diet.

Does this mean we should avoid diets/ calorie deficits?

No, absolutely not.

It simply means you should consider that frequency and duration of a caloric deficit have a direct impact on your metabolism and that a structured approach and a specific plan for after the diet are necessary in order to keep these negative effects to a minimum.

How-to keep “damage” or “adaptation” to a minimum:

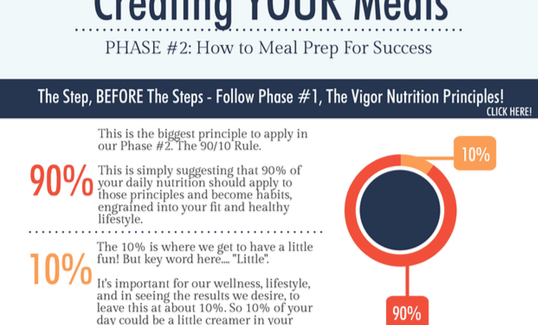

→ Keep the size of your deficit in check. Think minimal effective dose. Don’t start with a 25% calorie deficit if you could be losing weight with 10%. Leave something in the bag for later if necessary and this way you will also be able to retain as much of your muscle mass and performance (in and out of the gym) as possible. It is very likely that the bigger the deficit, the bigger the negative adaptations.

→ Keep up your strength training! Again, it will allow you to maintain as much lean body mass as you can during the deficit and it will keep your exercise activity thermogenesis high!

→ Keep your protein intake high (or actually even higher). Your protein levels should be highest when you are in a deficit. Once again, to maintain as much lean body mass as possible, but also to keep satiety levels high and keep the thermic effect of food as high as possible (since protein is the macronutrient with the highest TEF). In practical terms: set your protein at least at 1g/pound of body weight during the cut, you could even go up to as much as 2g if it increased your satiety and adherence.

→ Keep the time you spend in a deficit in check. We usually recommend not staying in a severe deficit for longer than 8-12 weeks at a time. The duration of a deficit is another factor that directly affects the effects of the adaptations. 8-12 weeks is usually a good amount of time where goals can be achieved and adaptations- physical and mental repercussions- kept to a minimum. After a deficit make sure you spend a good amount of time in a maintenance phase. If going into another cut, you want to make sure your body is absolutely ready for it (biofeedback high and your body is still responding to the deficit).

→ Consider incorporating refeed days or diet breaks. Refeed days (period of 24hrs-48hrs at higher calories, usually around maintenance with higher carb intake), can help to increase leptin for a short amount of time (the hormone that controls hunger and metabolic rate). The effect of refeed days on metabolic adaptation, especially with single refeed days, is still questionable and more research is needed on the topic.

However, often it is the mental aspect of refeed days that shows the biggest benefit. It gives the person dieting a day to look forward to, helping with cravings and replenishing our glycogen storages. However, refeed days are not to be seen as “cheat days”, since we are still controlling our calories rather than just controllably giving in to our increased hunger and cravings. Diet breaks, multiple days around maintenance calories, can be another way to “break up the diet” and help minimize the negative way, similarly to refeed days.

We can take diet breaks according to biofeedback (for example if sleep and performance are declining too much, cravings are getting to high etc), often every 4 weeks, sometimes only every 8 weeks. Just like refeed days, this really comes down to each individual, how your body reacts and more importantly – your personal preference. Some people do not like the idea of weekly refeeds and lower calories during the week, others find they can adhere better to the diet knowing they have regular refeeds coming up.

→ Lastly, and this is crucial, you need to have a plan in place for after the diet. If you don’t have a plan in place, chances are that with your increased hunger levels and your body’s desire to stock up for future “starvation periods” you will most likely overeat (and gain it all back or more). Even if you go back to eating the same exact foods you were eating before the diet, you will most likely gain fat, because of the increased likelihood to store fat now and also because your new maintenance level is not the same as the old.

So what can you do to prevent this? You could either slowly increase your calories until you find your new maintenance level (also known as reverse dieting – listen to our podcast to learn everything needed on Reverse Dieting, Here) or, depending on how big your deficit was, what sort of timeline you are on and if you would possibly even like to go into a gaining phase some time soon, you could increase in bigger increments. Which way you want to go about it highly depends on you and how important it is to you to stay lean throughout the whole process.

The purpose of this post was not to make you scared of dieting. It was simply to show you that certain “symptoms” are completely normal during a cut (for example feeling increasingly hungry), that your entire body is affected by a diet for longer than just the duration of the diet (down to a hormonal level) and why yoyo-dieting is so dangerous and usually leaves you worse off than before.

However, if you approach a diet with all the things we have spoken about in mind (most importantly the periodization of your diet) you can successfully lose fat, maintain lean muscle mass, eat an amount of food that allows you to perform well and feel good and stay healthy overall long term.

Resources:

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3943438/

- Fat Loss Forever, Dr. Layne Norton