Food Addiction: The Science Behind Our Cravings

You’ve just polished off a satisfying dinner, but inexplicably, you find your hand drifting toward a chocolate bar or a bag of chips an hour later. Why is it so hard to resist certain foods, even when we’re not hungry? For many, this might be more than just a lapse in willpower. It could be food addiction, a growing concern that is beginning to attract attention from both medical researchers and the public alike.

Comparable to substance dependence such as alcohol or narcotics, food addiction manifests through a complex interaction between neurobiological mechanisms and biochemical factors. In this context, certain foods, often those high in sugar, fat, and salt, can trigger a pleasure response in the brain that overrides signals of fullness and satisfaction. This creates a cycle of craving that some scientists think are as powerful as the one associated with substance abuse, leading to a pattern of compulsive eating that goes beyond the occasional indulgence. The consequences of food addiction are both immediate and long-lasting, affecting physical health, emotional well-being, and overall quality of life. In this article, we’ll cover everything you need to know about food addiction based on the latest science.

What is Food Addiction?

Food addiction is a term that you might think describes someone who just loves food a lot, but it’s more complex and scientifically nuanced than that. Although there’s no official definition of addiction universally agreed upon, it is generally described as a condition where a person is compelled to seek rewarding behavior even when it has negative consequences (Sussman & Sussman 2011). For instance, someone addicted to gambling might continue to gamble even at the expense of their financial stability and relationships.

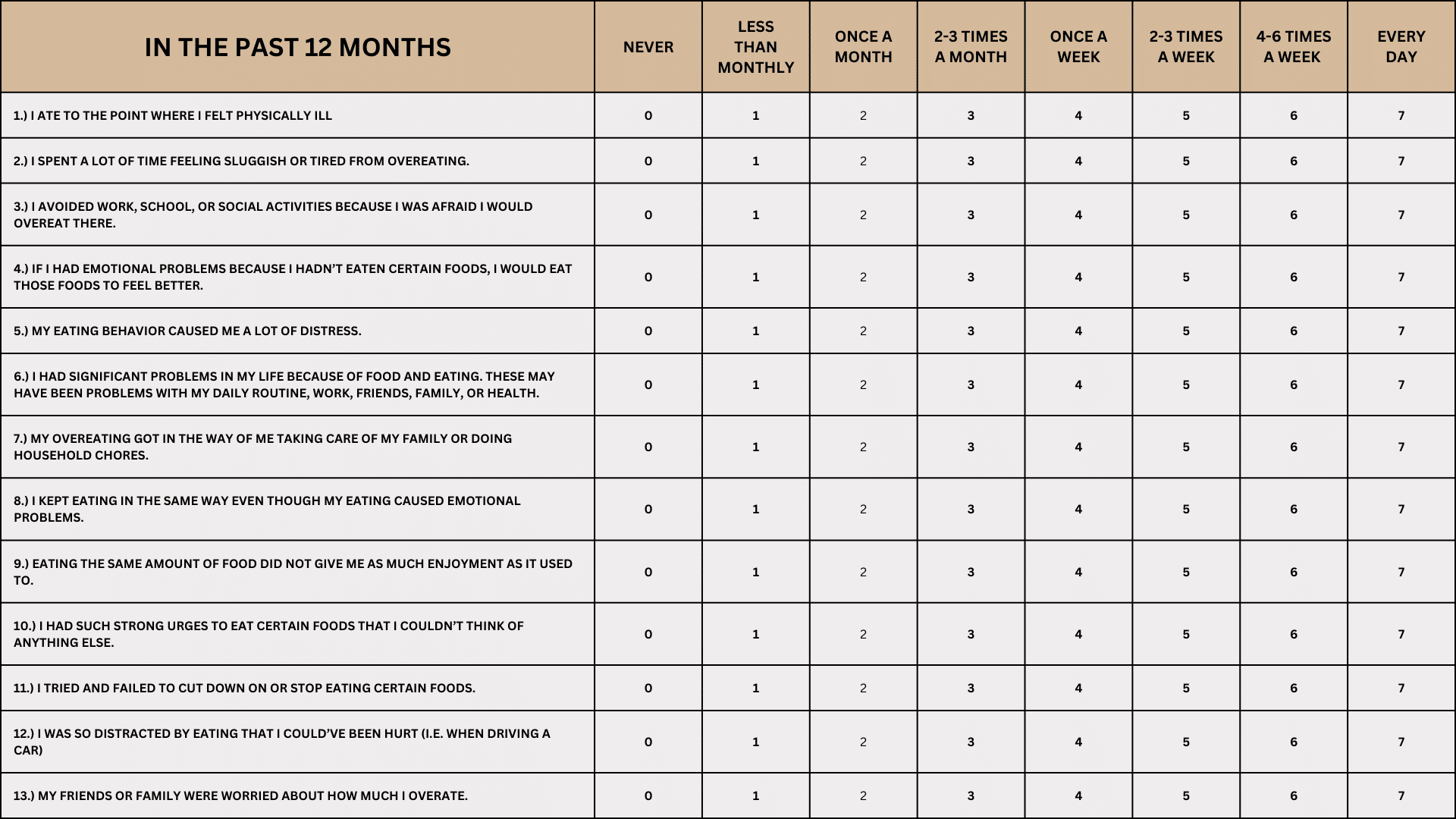

While the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) has yet to recognize food addiction as a clinical diagnosis, researchers have created the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS) as a tool to assess it. The YFAS is a 25-question survey that uses the seven features of addiction (Gearhardt et al 2009). In 2016, a revised version, known as YFAS 2.0, was developed to align with the updated criteria for Substance Use Disorder as outlined in the latest edition of the DSM-5. The YFAS 2.0 evaluates addictive-like eating habits based on 11 specific diagnostic criteria from the DSM-5, aiming to provide a more comprehensive and updated measure.

Below you’ll find a modified version of the YFAS, asking about your eating habits over the past year.

When the following questions ask about “certain foods” please think of ANY foods or beverages similar to those listed in the food or beverage groups above or ANY OTHER foods you have had difficulty with in the past year.

According to this scale, you can be classified as having “food addiction” if you experience at least three of the seven features and have significant distress or impairment because of your eating behaviors. The severity of your scoring, determines the likelihood of a true food addiction being present. Seek nutritional consultation if you find yourself marking multiple symptoms, with a high frequency.

The brain chemistry behind food cravings is remarkably similar to that of substance abuse (Tang et al. 2012). Both activate the release of dopamine, often called the “motivation chemical.” This is especially true for processed foods, which are high in fats and refined carbohydrates, and can, therefore, trigger addiction-like eating behaviors (Schulte et al 2015). So, while the scientific community hasn’t reached a consensus on whether food addiction is a valid medical term, there’s no denying that certain foods can create strong cravings and drive overeating.

The Neurochemistry of Food and Addiction

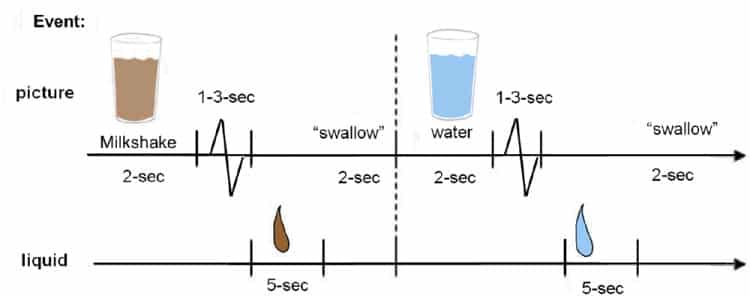

Have you ever wondered if food can be as addictive as substances like alcohol or drugs? Well, a study sought to answer this specific question by examining the brain activity of 48 healthy young women, ranging from lean to obese. Researchers used advanced imaging techniques like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to observe how the brain reacts to receiving and even just anticipating a tasty food item—in this case, a chocolate milkshake. The aim was to see if higher food addiction scores correlate with brain activity patterns typically seen in substance dependence.

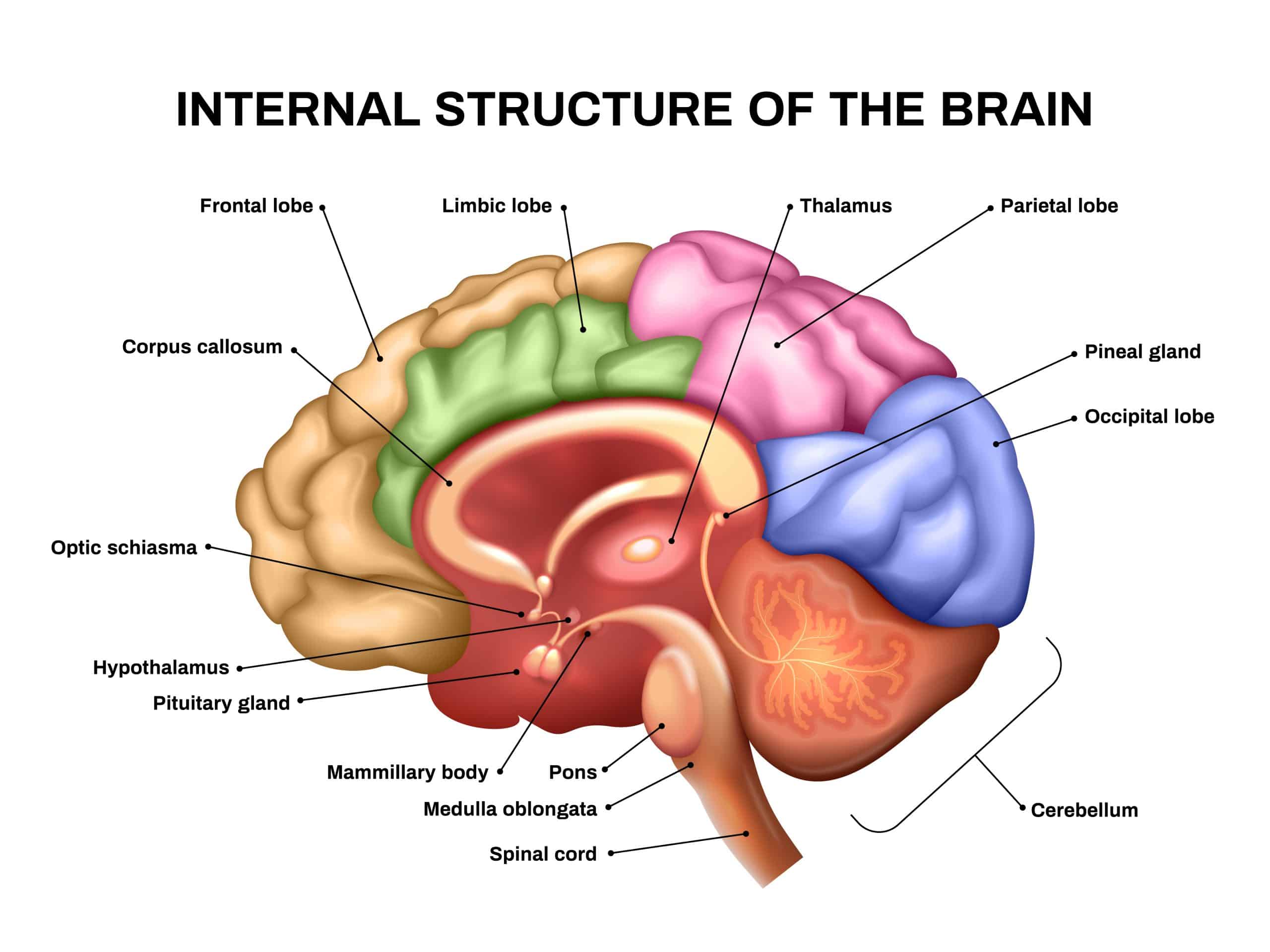

What they found was striking: those with higher food addiction scores displayed more intense activation in certain brain regions, like the anterior cingulate cortex and the medial orbitofrontal cortex, when they anticipated receiving food. These brain areas are known to be linked to reward and emotional processing. Additionally, those with higher scores showed increased activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the caudate, areas associated with decision-making and pleasure, respectively. Interestingly, these participants also showed reduced activity in the lateral orbitofrontal cortex, a region linked with inhibitory control, when they actually received the food. This pattern of brain activity resembled what is typically seen in substance dependence, further bolstering the idea that food can indeed be addictive for some people.

What Makes Some Foods So Hard to Resist?

Before we dive into more science, let’s acknowledge a question that many of us have probably asked ourselves: “Why can’t I stop eating certain foods even when I know they’re bad for me?” It’s not just a lack of willpower; there might be a scientific reason why some foods are incredibly hard to resist.

Now, let’s look at a study that provides eye-opening insights into why some foods may be as addictive as drugs, shedding light on the physiological reasons behind our eating choices.

A study examined the eating behaviors of undergraduate students. In the first part of the study, 120 participants filled out the Yale Food Addiction Scale and then had to choose which among 35 different foods were most likely to lead them to exhibit addictive-like eating behaviors. In the second part, involving 384 participants, the study dug deeper into which specific food attributes—like fat content—were linked to addictive eating tendencies. The findings revealed that processed foods, particularly those high in fat and with high glycemic load, were the most frequently associated with addictive-like eating behaviors.

The study’s conclusions serve as preliminary evidence that not all foods are created equal when it comes to their potential for addiction. Highly processed foods, rich in fats and/or refined carbohydrates, appeared to have a particular link to addictive eating habits. The hypothesis suggests these foods might share pharmacokinetic properties—such as a concentrated dose and rapid absorption rate—with drugs of abuse.

What does that mean? Well, just like certain drugs, these foods deliver a quick, intense dose of pleasure, making them more likely to be associated with addictive behavior.

Is Sugar Really That Addictive?

You’ve likely heard that sugar is as addictive as a drug, right? Well, let’s explore what the research has to say about it. Often, the “sugar is addictive” argument comes from animal studies, and there’s surprisingly little human-based evidence supporting sugar addiction according to the standard clinical criteria. A recent study aimed to bridge this gap and understand whether foods rich in sugar might lead to addiction-like behaviors, and how this correlates with body weight and mood.

This research study aimed to get to the bottom of the “sugar addiction” theory by examining a sample of 1,495 university students. The study assessed the participants using the Yale Food Addiction Scale and analyzed their Body Mass Index (BMI) and emotional well-being.

Astonishingly, 95% of the participants experienced at least one symptom of food dependence based on the Yale Food Addiction Scale, and 12.6% met the criteria for food addiction. But here’s the kicker: the majority faced these issues with high-fat savory (30%) and high-fat sweet (25%) foods, rather than foods primarily containing sugar (5%).

The findings question the popular notion that sugar is a main driver of food addiction and weight gain. Instead, the study supports the broader scientific perspective that the energy density of food and personal experiences with eating are more significant factors in food-related psychological effects and excessive calorie intake. So next time you hear that sugar is “as addictive as a drug,” remember that the science tells a more nuanced story—one that points to a range of factors contributing to our complicated relationship with food.

The Addictive Nature of Chocolate:

More Than Just a Sweet Treat?

Ever wondered why chocolate seems to have a harder pull compared to other foods? A study aimed to understand this by investigating the psychoactive effects of chocolate with varying levels of sugar, cocoa, and fat. Let’s dive into what makes chocolate so irresistible and potentially addictive.

The study required participants to sample chocolate with differing cocoa percentages (90%, 85%, 70%, and milk chocolate) and then answer questions on the Psychoactive Effects Questionnaire (PEQ). Interestingly, as the sugar content in the chocolate increased, so did its psychoactive effects. Specifically, the number of positive responses started to climb after participants tasted the 90% and 85% cocoa chocolates. However, the amount of chocolate consumed did not correlate with Binge Eating Scale (BES) scores or self-reported scores on the PEQ. What does this mean? Essentially, the higher the sugar content, the more the chocolate activates psychoactive responses, supporting the notion that chocolate has a unique propensity to trigger addictive-like eating behaviors.

The results suggest that chocolate doesn’t just please your taste buds; it impacts your brain’s dopaminergic systems, which are associated with reinforcement and mood improvement. So, the next time you find yourself irresistibly drawn to a chocolate bar, remember that it’s not just your sweet tooth talking — your brain is in on the craving too.

The Role of Ghrelin and Leptin in Food Addiction:

New Insights from a Population-Based Study

Ghrelin is a hormone known for stimulating appetite, particularly for highly palatable foods, by interacting with the brain’s reward system. It has also been implicated in the development of addiction disorders, such as alcohol dependence. Ghrelin levels typically rise during fasting periods and increase further when a meal is anticipated. On the other hand, leptin is a peptide hormone produced in fat cells that may be involved in the brain’s reward circuitry. Limited research suggests leptin plays a role in cravings associated with nicotine and cocaine addiction.

Given the sparse research on the relationship between food addiction and ghrelin, a recent study aimed to explore the association between serum levels of ghrelin and leptin and food addiction scores. 909 subjects from the LIFE Adult cohort were analyzed. Various factors such as age, sex, alcohol consumption, smoking status, BMI, cortisol concentrations, and scores on mental health scales were accounted for in the univariate multiple linear regression models, with YFAS scores serving as the dependent variable.

The study found a significant association between leptin serum levels and YFAS scores in men. Specifically, men with higher leptin levels had significantly higher YFAS scores than those with lower levels. Interestingly, no such correlation was found for ghrelin levels.

These results are consistent with existing literature, indicating that leptin may have a role in food addiction. In contrast, their findings did not support a significant relationship between ghrelin levels and food addiction scores, suggesting that ghrelin might not be a key player in food addiction as previously speculated.

Evaluating the Addictive Nature of Highly Processed Foods:

A Comparison with Tobacco Products

The scientific community has long debated the addictive qualities of highly processed foods, but standardized criteria to assess their addictive nature have been lacking. In a recent review, scientists suggested that the 1988 Surgeon General’s criteria for evaluating the addictiveness of tobacco products could be a suitable framework for examining highly processed foods. These criteria focus on compulsive use, psychoactive effects, and reinforcement of behavior, elements that are also observed in the consumption of highly processed foods.

Much like industrial tobacco products, highly processed foods have psychoactive properties that lead to strong cravings and compulsive consumption. Notably, the foods most commonly reported to trigger addictive-like eating behaviors are highly processed foods rich in refined carbohydrates and added fats. The manufacturing process of these foods is designed to expedite the delivery of these substances by removing elements like fiber that would otherwise slow down the rate of eating and absorption. Similarly, tobacco products (dip, cigarettes, vaping, etc) contain chemicals and have been optimized by the tobacco industry to enhance their addictive nature. Highly processed foods are complex mixtures that can’t be reduced to just one addictive component or mechanism.

On a behavioral level, food addiction shares many characteristics with other eating disorders, complicating the establishment of clear diagnostic criteria. While the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood, elements such as reward dysfunction, impulsivity, and emotional dysregulation have been identified as common factors in both eating disorders and addictive behaviors. There is also evidence to suggest that genetic predispositions may influence cravings for carbohydrates and saturated fats.

Understanding the clinical profile and mechanisms behind food addiction is crucial for developing targeted prevention and treatment strategies. This study suggests that applying the 1988 Surgeon General’s criteria may be a useful approach for scientifically evaluating the addictive nature of highly processed foods..

Food Addiction vs. Other Eating Disorders

Food addiction and traditional eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder share similarities but are distinct conditions with unique diagnostic criteria. Understanding the nuances between them can help people develop more effective treatment plans.

Behavioral Characteristics

To grasp the full scope of these conditions, let’s first examine the behavioral aspects that define food addiction and other eating disorders. Both food addiction and eating disorders involve dysfunctional relationships with food that significantly impact daily functioning and overall well-being. For example, food addiction is characterized by a compulsive consumption of specific types of highly palatable foods despite negative consequences. In contrast, eating disorders like anorexia involve extreme food restriction, bulimia entails cycles of binging and purging, and binge-eating disorder focuses on episodes of extreme overconsumption.

Psychological Mechanisms

Understanding the psychological factors that drive these disorders can offer a deeper insight into how they manifest and persist. Common psychological mechanisms, such as emotional dysregulation, impulsivity, and reward dysfunction, are observed in both food addiction and other eating disorders. Both conditions often co-occur with other psychological issues like depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, complicating the diagnostic and treatment landscape.

Diagnostic Criteria

Effective treatment requires a multifaceted approach; hence, it’s crucial to understand the specific strategies used for managing food addiction as compared to other eating disorders. One key difference between food addiction and traditional eating disorders lies in the established criteria for diagnosis. Traditional eating disorders are well-established in medical literature and have clear diagnostic criteria outlined in the DSM-IV. Food addiction, however, is a more recent concept and lacks universally accepted diagnostic criteria. While instruments like the YFAS attempt to quantify food addiction, the condition is not officially recognized as a distinct psychiatric disorder in the DSM-5.

Biological Factors

Genetic factors may influence both food addiction and other eating disorders, although more research is needed in this area. Certain hormones, such as ghrelin and leptin, are being studied for their role in food addiction. Similarly, alterations in neurotransmitter systems like dopamine and serotonin have been implicated in other eating disorders.

Treatment Approaches

Both conditions require multidisciplinary treatment involving nutritional counseling, psychotherapy, and possibly medication. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been effective in treating eating disorders and shows promise for food addiction as well. However, treatments for traditional eating disorders are generally more established, with a range of pharmacological options available.

In conclusion, while food addiction and other eating disorders share some similarities in behavioral characteristics and underlying psychological mechanisms, they are distinct conditions that require individualized approaches to diagnosis and treatment. Further research is needed to fully understand the complexities of these disorders, especially for developing targeted interventions for food addiction.

Consequences of Food Addiction

The consequences of food addiction can be severe and multifaceted, affecting both physical and mental well-being. Physically, an addiction to food often leads to obesity, which in turn increases the risk for a host of other health issues such as diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension. The cycle of binge eating and subsequent guilt can also contribute to gastrointestinal issues. Mentally, food addiction can lead to a range of psychological distresses including depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem. The emotional toll can be exacerbated by social stigmatization and the frequent misunderstanding of food addiction as a lack of willpower rather than a medical condition. Furthermore, the pervasive nature of addictive foods—often cheap and easily accessible—makes it challenging for individuals to break free from the cycle of addiction. This not only strains personal relationships but can also lead to socioeconomic consequences as productivity declines and medical bills rise. Therefore, addressing food addiction is not just a matter of personal health but also an issue with broader societal implications.

Tackling Food Addiction

Tackling food addiction requires a holistic approach for effective management. A combination of psychological counseling, medical evaluation, and nutritional guidance is typically recommended. CBT is often used to help individuals understand the triggers and thought patterns that lead to addictive eating behaviors. Meanwhile, medical professionals can evaluate any underlying conditions that may contribute to food addiction, such as hormonal imbalances or medications that can increase appetite.

Nutritional counseling can provide practical tools for making healthier food choices and understanding portion control. Support groups, either in-person or online, can also offer a community of understanding and shared experience that can be invaluable for maintaining long-term behavioral change. As each person’s experience with food addiction is unique, a tailored treatment plan is often the most effective route to recovery. In addition to these approaches, working with an online fitness coach can provide the added benefit of regular, personalized exercise regimens and accountability, which not only improve physical health but can also positively impact mental well-being and self-control.

Final Thoughts

To sum up, food addiction is a complex issue that shares characteristics with both substance abuse and other eating disorders. It has severe consequences for both physical and mental health, affecting not just weight but also emotional well-being. Addressing food addiction requires a multi-faceted approach that may include medical evaluation, psychotherapy, and changes in diet and exercise. Online fitness coaches can offer additional support by creating personalized exercise plans and fostering accountability. Understanding the nuances and impact of food addiction is crucial for both healthcare providers and individuals, as it can inform better prevention and treatment strategies.