Does Your Body Adapt To NEAT Or Walking, Making Your Step Count Less Effective At A Certain Point?

Total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) is the net amount of energy utilized by people to maintain core physiological functions and to allow movement. The four main components of energy balance determine TDEE: Basal metabolic rate (BMR), the thermic effect of food (TEF), which is also called diet-induced thermogenesis, and the energy expended for physical activity (EAT), and the energy expended we use to move around, which is known as non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT).

The importance of NEAT becomes obvious when considering the following: the variability in BMR between individuals of similar age, BMI and of equal gender ranges around 7-9%, while the contribution of TEF is 10%. Therefore, BMR and TEF are mostly fixed in amount and account for approximately three quarters of daily TDEE variance. As EAT is believed to be negligible in everyone except elite athletes who train multiple hours per day, NEAT thus represents the most variable component of TDEE between people. In fact, NEAT is responsible for 6-10% of TDEE in individuals with a mainly sedentary lifestyle and for 50% or more in highly active subjects.

NEAT consists of all the energy used while working, during leisure activity, sitting, standing, walking, and everything else that isn’t exercise. NEAT can be increased by parking farther from the store/work, taking the stairs, and listening to your Apple watch telling you to stand every hour.

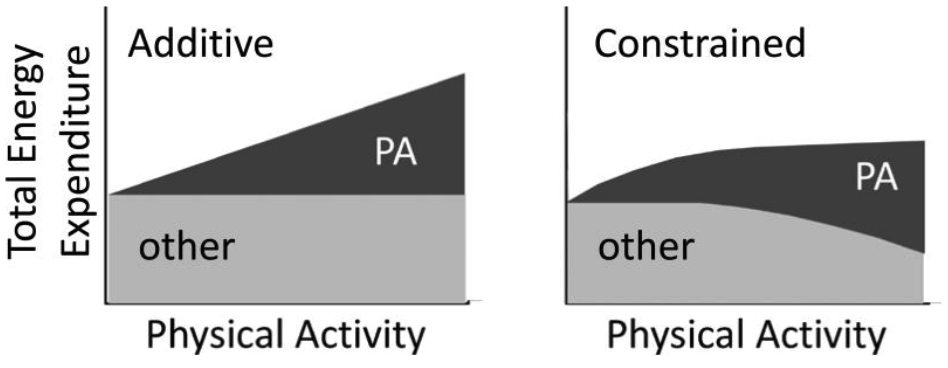

However, there is a theoretical limit of how much you can increase your NEAT, which is known as the constrained energy theory. This theory was developed by Dr. Herman Pontzer and suggests that the body adapts to increased physical activity by reducing energy spent on other physiological activity, maintaining total energy expenditure within a narrow range.

Another theory, known as the additive total energy expenditure model, suggests that total energy expenditure is a linear function of physical activity, and variation in physical activity energy expenditure determines variation in total energy expenditure.

Figure 2. Schematic of Additive total energy expenditure and Constrained total energy expenditure models. Image from Pontzer et al., 2017

The constrained energy theory is based on Pontzer’s idea that TDEE is a relatively stable homeostatically controlled trait that is more a reflection of our evolutionary past than our current lifestyle. Pontzer clearly demonstrates in one paper that in several different studies of birds and mammals, physical activity has a diminishing effect on TDEE, with daily energy throughput constrained within some physiological window.

Pontzer’s seminal work on TDEE used doubly labeled water in an adult sample (n = 30) of traditional hunter-gatherers. Despite high levels of activity in this population, Pontzer and colleagues found no difference in TDEE between hunter-gatherers and a comparative sample of European and American adults after controlling for fat-free mass. However, he did find that some populations of subsistence farmers do have marginally greater TDEE after controlling for body size, which may indicate some flexibility in overall TDEE.

Interestingly, exercise can decrease NEAT in some people. This could be bad news for people who are trying to diet, especially if they do extra cardio yet their NEAT drops for the rest of the day.

Another relevant study showed that a single exercise session did not affect NEAT, which remained the same before the exercise session, the day of the exercise session, and for several days after the session. There were also no differences between the moderate and high intensity sessions. A limitation to this study was that the exercise was walking (fast vs slow).

Another study on the topic found that people who completed a resistance training or walking program did not complete other physical activity during their leisure time. The findings of this study could be due to people not having time for more than one type of physical activity.

Taken together, all of these studies suggest that people may reduce their NEAT if they exercise consistently or if they suddenly increase the amount they exercise. One way around decreasing NEAT is to wear activity trackers to help you keep track of your steps. Steps aren’t the only NEAT, but they do make up a large part of it.

In summary, it does not appear that your body adapts walking if you keep everything else the same, rather some people adjust other subconscious factors so it may appear to have no effect.