Training Intensification Tip Part 2: Inter-set Stretching & Stretch Mediated Hypertrophy

Intensification techniques, also known as advanced techniques, are a scientific term for methods like drop-sets, cluster sets, pre-exhaustion (or pre-fatigue), rest-pause training, reciprocal sets, overcoming-isometrics, and overload-eccentrics. Each technique has a slightly different purpose and can potentially be used in certain scenarios to maximize how you adapt to training, whether we’re talking strength or hypertrophy (muscle growth). In part 1, we covered the science and application behind super-sets. In this article we’ll be covering inter-set stretching and stretch-mediated hypertrophy, so that you can understand what these methods are AND how (or if) you can add this training intensification technique into your training program.

Science Behind Stretching For Hypertrophy

The science behind testing advanced techniques is fairly small and involves a lot of considerations, so below we’ve focused on the chronic studies, lasting more than four weeks, more so than the acute studies, which are generally only a single exercise session. However, if an acute study has something interesting it will be mentioned. We do this as a way to ensure all the research is considered, but only the most insightful and applicable research is utilized in our guidance for you!

Research Review: Inter-Set Stretching

Inter-set stretching is based on the idea that if muscles are actively or passively stretched between sets, the additional mechanical stimulus may enhance the hypertrophic effect of traditional strength training. The two main methods to do this are to lower the weight and allow the weight to stretch your muscles or keep the weight the same as your working set. For example, when doing a chest cable fly you would complete your set, then rest for 15-30 seconds between each set in a stretched position (pretend you’re gliding).

We have a few studies to give us insight on inter-set stretching. Studies in rabbits, rats, and birds have suggested that passive stretching can cause muscle hypertrophy. On the other hand, some human research suggests that stretching for long periods may decrease strength and increase fatigue although the effect is context specific. A previous (unpublished) study found that trained individuals performing inter-set stretching increased the muscle thickness of their gastrocnemius more than traditional resistance-training.

In one study, 8 weeks of traditional strength training (TST) and inter-set stretching combined with TST was tested. Both groups performed 6 strength exercises encompassing the whole body (bench press, elbow extension, seated rows, biceps curl, knee extension, and knee flexion) performing 4 sets of 8-12 repetition maximum. The inter-set stretching group performed unweighted static passive stretching, at maximum stretch, for 30 seconds between sets. Both groups performed training sessions twice a week. The authors found that inter-set stretching was not superior or inferior to traditional training. This was likely due to the fact that the participants completed simple static stretching.

In the next study on inter-set stretching, participants were randomly assigned into two groups and underwent an 8-week training program. Subjects in the inter-set stretching group completed an additional loaded stretch for 30 second at 15% of their working load from the prior set during the inter-set rest periods. Oddly, the inter-set stretching group rested for 90-second rest between sets while the TST group rested for 120 seconds. The results ultimately suggest the addition of a loaded inter-set stretching does not affect muscular adaptations either positively or negatively in resistance-trained men.

A more recent study evaluated changes in muscle strength and hypertrophy in the calf muscle, comparing TST and inter-set stretching in young men who had not performed lower-body resistance training for at least 6 months. The participants completed seated and straight-leg calf raise exercises, twice per week. The inter-set stretching group completed a 20-second stretch between sets with the same load they used during the set and both groups rested for the same amount of time between sets. The authors found that inter-set stretching was beneficial for hypertrophy in the soleus, but not the gastrocnemius muscle in the calf.

Taken together, these studies suggest there isn’t likely a benefit or detriment to adding inter-set stretching to your training. It’s not going to make much of a difference in the short-term (8-12 weeks) and long-term we don’t have any data.

Research Review: Stretch-Mediated Hypertrophy

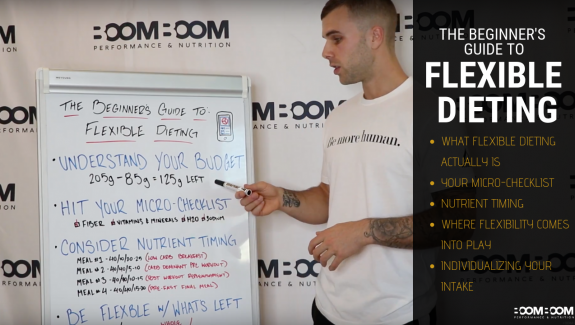

Now that we’ve covered inter-set stretching, we can move on to what’s known in the literature as stretch-mediated hypertrophy. Stretch-mediated hypertrophy is the processes of a muscle reaching it’s fully lengthened position and potential, while under load. This is a newly popular topic that is currently going through a lot of research, so the studies we can present on this specific topic are fairly limited but nonetheless are extremely useful. We can also pull from research done on strength training with full ranges of motion, to support our case for stretch-mediated hypertrophy.

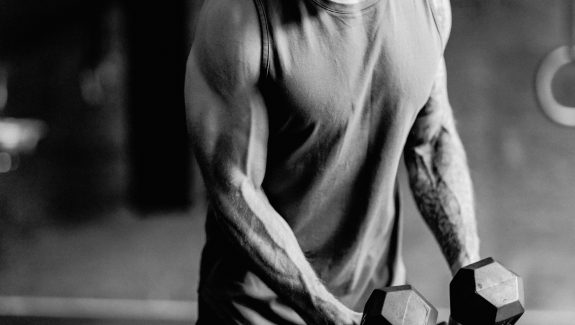

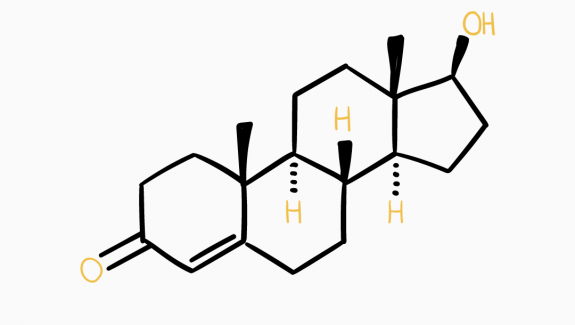

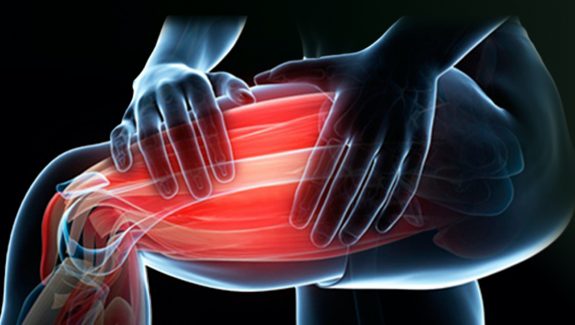

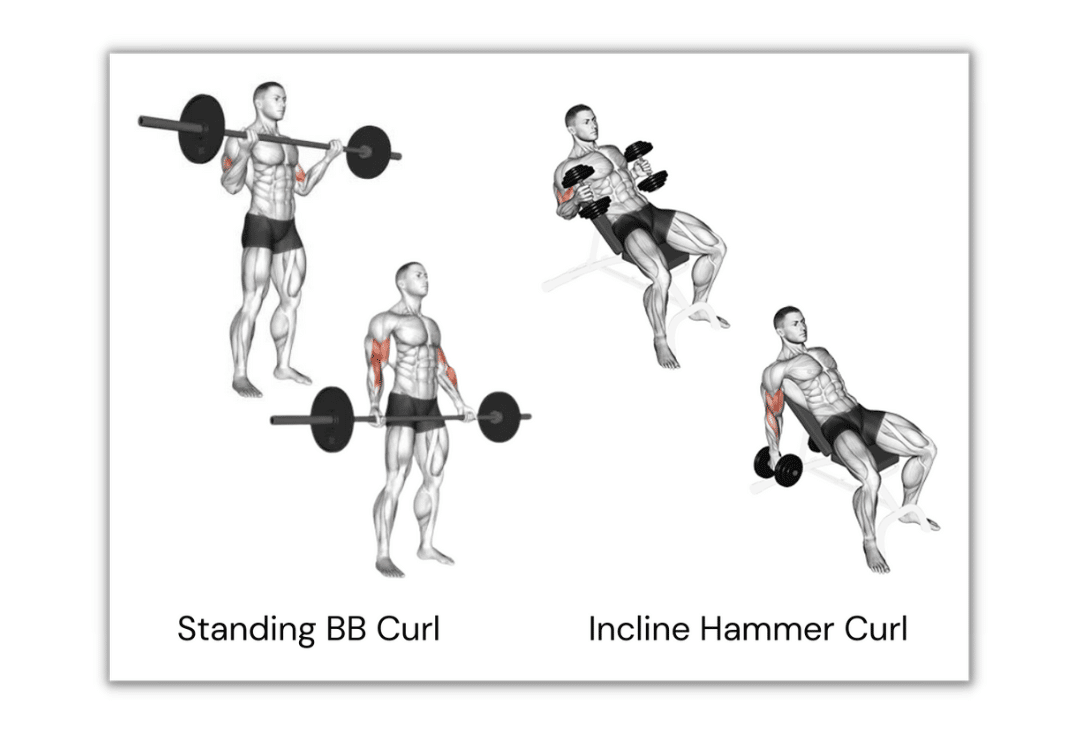

To further describe what stretch-mediated hypertrophy is and looks like, to help you truly understand the what before we dive into the why, I want you to think of a standing barbell curl vs. an incline bench hammer curl (see image below):

As you can see in the image, the standing barbell curl will be limited in regards to stretch-mediated hypertrophy. This is because the barbell will reach your hip and end your ability to take the range of motion any further beyond that point.

The dumbbell incline hammer curl is not limited in it’s range of motion by anything outside of the muscle physical capabilities. This is because of the nature of what dumbbells allow and the positioning of the incline bench, which is allowing the shoulders to go into slight extension. When doing this, we see an increase in stretch-mediated hypertrophy of the biceps, due to the incline hammer curl’s ability to allow the bicep’s range of motion to be extended further beyond what a normal barbell curl allows. From this, we see a greater amount of load placed on the muscle in the lengthened (stretched) position.

We have a few studies to show just how important the lengthened portion of an exercise is for hypertrophy, which may influence our exercise selection and decision making in regards to what intensification techniques we implement into our training.

The first study to bring up is a recent one (2021) that compared lying leg curls to seated leg curls. In the study they took one group of individuals who performed the same exact training program for 12 full weeks. In the training program, however, one leg performed seated leg curls while the other leg performed lying leg curls. Both exercises do achieve a full range of motion, in regards to knee flexion – but there is a difference between a joints full ROM and a muscles full ROM. If the joint goes into full flexion and extension, then it accomplishes a full ROM. However with a muscle, it may require other joints to change positions in order for it to accomplish it’s full ROM (which again, is a fully lengthened and shortened position).

The study showed that the leg performing seated leg curls resulted in considerably more muscle growth in the hamstrings. The findings of this study indicates that the exercise that places more emphasis on the stretched position, potentially loading that stretched position more, is likely to be the muscle that has the greatest growth potential.

Another recent study found that in certain exercises, partial ranges of motion may actually be more beneficial than full range of motion. At face value, this actually contradicts the many studies that have been published over the years showing that a full ROM is almost always better than a partial ROM for hypertrophy (muscle growth).

However, what was interesting and extremely valuable about this study is that they did not run with the typical partial ROM lifting you see most bro’s do in the gym. Usually we see someone stacking too many plates on a leg press and barely squeezing out quarter reps for their entire set. However, we never see that same lifter take the repetition all the way to the bottom, accomplishing a full ROM initially, and then sitting in the BOTTOM of that leg press performing partials. This is because it would require far LESS weight to perform properly, rather than MORE. However, this is exactly what proper partial ROM reps should likely look like.

In this study, researchers separated the participants into 4 groups: (1) an “end range ROM group” who performed only the top 30° of movement near full knee extension, (2) a “stretch ROM group” who performed only 35° of movement in the bottom, (3) a “full ROM group” who performed both of the above ROMs (reaching 100° of movement), and (4) a “varied ROM group” who alternated between the initial stretch ROM and the final end range ROM workouts.

Most expected that the full ROM group would have the greatest rates of muscle growth in this study, but in fact it was the stretch-only group that gained the most muscle. Which once again allows us to give more credit to the stretch-mediated hypertrophy theory.

Practical Application: How To Use Stretching For Hypertrophy

Advanced training techniques could provide an additional stimulus to break through plateaus for trained subjects and prevent excessive monotony in training. As you can see, there is more research to guide us than in Part 1, so we’ve given some practical application for both of these intensification techniques below.

Inter-Set Stretching

Inter-set stretching doesn’t seem to be an advanced technique that is far superior to traditional training. That said, it could be a useful way to add mechanical stimuli to your working sets. While I wouldn’t use this method for a specialization cycle (e.g., chest focus for 12 weeks) it might be good to use sparingly to keep things interesting, especially for those who are untrained or returning from a break. In terms of protocol, it seems like inter-set stretching with the same load used as the working set provides the most benefit.

However, we’re just not that impressed with the research here and feel that the main use of stretching for hypertrophy is likely going to be to use it, outside of your training sessions, as a way to increase flexibility so that you can begin accomplishing a full range of motion — that is, if you’re lacking in your ability to do so to begin with. The other optimal way to utilize it would be with stretch-mediated hypertrophy; however, as you can see, neither of these suggestions are actually FOR inter-set stretching… but rather for other types of hypertrophy focused stretching methods.

Stretch-Mediated Hypertrophy

Although we do have semi-correlated evidence in other studies that go way back, stretch-mediated hypertrophy itself is still in it’s infancy of the research. It’s looking very bright, though, and we’re excited to see what’s to come in this line of research.

That being said, our recommended use of this is to actually use it regularly with a normal level of effort and intensity. Rather than saving it to be used as an intensification method that takes your training from ground level to level 100.

What we recommend is to train with a full range of motion as often as you can, without causing injury, and ensure that you’re utilizing exercises that emphasize not just the stretched portion of the range, but also the shortened range as well. These studies lead us to believe that the stretched position is likely more beneficial, but that doesn’t mean that it’s the ONLY beneficial portion of the range of motion during an exercise.

A study lead by Chris Barakat showed better muscle growth when varying the joint angle, encouraging multiple ranges of motion for both the joint and the muscle, compared to limiting the exercise variations to just one joint angle and range of motion. This means we should vary our exercises and utilize multiple ranges of motion, to accomplish the best gains.

Knowing that, we’d recommend that at least 1/3, if not 1/2, of your exercises lean towards greater ranges of motion that place a large emphasis on the stretched portion of the exercise. This could mean changing the variation all together or utilizing a different piece of equipment to emphasis a greater ROM, but it could also simply mean slowing down at that last part of the ROM in order to place a greater amount of time under tension in the stretched portion of the ROM.

You can also crank up the intensity a bit by performing extended-set-partials. You can do this on a DB Bench Press, for example, by first accomplishing all your prescribed reps and then following the final full ROM rep with a maximum amount of partial-repetitions in the bottom portion of the lift. Doing this allows you to accomplish all your full ROM reps and then complete a large amount of reps in the most hypertrophic range of motion there is; the stretched position.

Conclusion

More and more research is coming out in this area, so stay tuned with what the evidence based fitness community brings out AND be on the look out for more content from us on the topic, because we’re sure to update this as more research comes out.

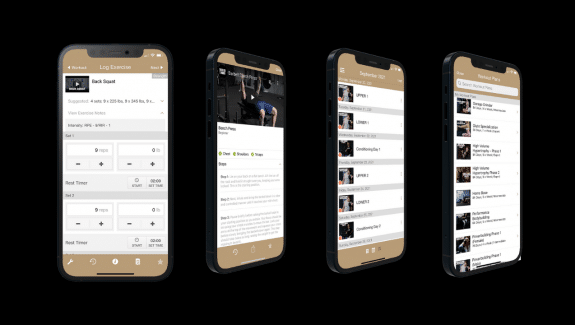

If you want to immediately learn how to apply some of this into your training, check out our workout app: The Tailored Trainer.

References:

- Fowles JR, Sale DG, MacDougall JD. Reduced strength after passive stretch of the human plantarflexors. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2000;89(3):1179-1188.

- Chaabene H, Behm DG, Negra Y, Granacher U. Acute effects of static stretching on muscle strength and power: an attempt to clarify previous caveats. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1468.

- Evangelista AL, De Souza EO, Moreira DCB, et al. Interset stretching vs. Traditional strength training: effects on muscle strength and size in untrained individuals. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33 Suppl 1:S159-S166.

- Wadhi T, Barakat C, Evangelista AL, et al. Loaded inter-set stretching for muscular adaptations in trained males: is the hype real? Int J Sports Med. 2022;43(2):168-176.

- Every DWV, Coleman M, Rosa A, et al. Loaded inter-set stretch may selectively enhance muscular adaptations of the plantar flexors. PLOS ONE. 2022;17(9):e0273451.

-

Maeo et al. (2021). Greater Hamstrings Muscle Hypertrophy but Similar Damage Protection after Training at Long versus Short Muscle Lengths. PMID: 3300919

-

Pedroso et al. (2021). Partial range of motion training elicits favorable improvements in muscular adaptations when carried out at long muscle lengths. PMID: 33977835

-

Chris Barakat et al. (2019). The Effects of Varying Glenohumeral Joint Angle on Acute Volume Load, Muscle Activation, Swelling, and Echo-Intensity on the Biceps Brachii in Resistance-Trained Individuals. PMID: 31487841