Muscle strains seem to happen at the most inopportune time. They are a common injury that can be caused by overuse or sudden force on a muscle during a workout, while playing a sport, or even while picking up your kid. Muscle strains cause pain, swelling, tenderness, and most commonly occur in the hamstrings, lower back, and calves. Depending on the severity of the strain, you may experience weakness or difficulty moving the affected muscle for weeks. However, with the right steps, you can reduce your recovery time and get back to your normal training in no time.

Exercising with a muscle strain can be intimidating. After all, it feels pretty counterintuitive to exercise something that is painful or that you injured. However, research shows that working out with a muscle strain can be beneficial for healing the strain quickly and for improving the overall strength of the muscle. In this blog, we’ll cover the basics of a muscle strain, how to rehabilitate it, and other things to consider so it doesn’t slow down your training progress (another common question – is muscle soreness required if I want to build muscle? Read this post for that answer).

So, can you workout with a muscle strain? The short answer is yes, but it’s important to be mindful of your injury and make sure you’re taking the proper precautions not to make the injury worse.

What is a muscle strain?

Let’s first define what a muscle strain is. A muscle strain, also known as a pulled muscle, occurs when a muscle is overstretched or torn. This can happen due to a sudden movement, overexertion, or even from a lack of warm-up prior to training. There are different types of muscle strains: grade I, grade II and grade III.

What are the types of muscle strains?

Grade I strains are considered mild and typically involve a small number of muscle fibers. These strains typically heal within a few weeks with proper treatment and physical therapy.

Grade II strains are considered moderate and involve a larger number of muscle fibers. These strains can take longer to heal and may require more aggressive treatment.

Grade III strains are considered severe and involve a complete tear of the muscle. These strains can take several months to heal and may require surgery.

The amount of time required to recover from a muscle strain depends on the type of muscle that is injured and the Grade of the strain (I, II, or III). Muscles responsible for stability and posture, such as the rotator cuff and trunk muscles, typically take longer to heal than muscles used for movement, such as the biceps and quadriceps. Furthermore, muscles that are used more frequently may take longer to heal than those that are used less often because they are constantly active.

If you want a deep-dive on the physiology behind how a muscle strain occurs and heals, read the next two paragraphs, if not skip to the next section on “How do I rehabilitate a muscle strain?”

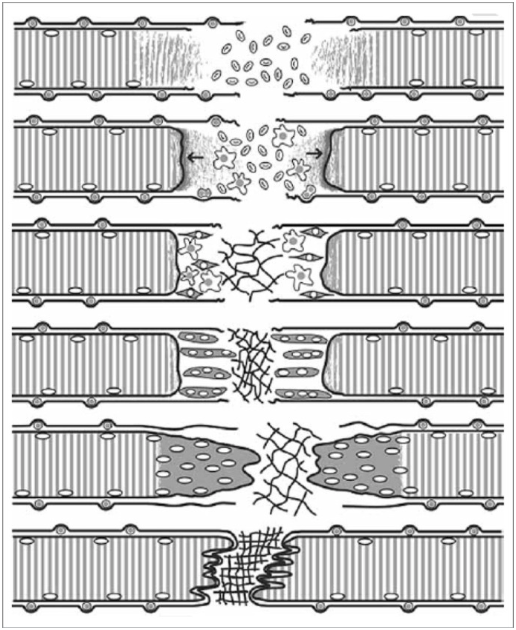

In muscle strains, the myofibers are usually exposed to an excessive tensile force that causes a shearing injury. This leads to the myofibers, the basal lamina, the mysial sheaths, and the blood vessels in the endo- or perimysium being torn. The rupture usually occurs close to the myotendinous junction, which is located within the muscle belly and attaches the myofibers to the intramuscular fascia.

Healing from a muscle strain follows a fairly consistent pattern. Three distinct phases of healing have been identified: destruction, repair, and remodeling. During the destruction phase, the ruptured myofibers become necrotized and the gap between the stumps is filled by a hematoma. The repair phase begins with phagocytosis of the necrotized tissue by monocytes and the activation of satellite cells. These cells contribute to forming myoblasts, which then fuse to form myotubes. During the remodeling phase, the regenerating myofibers form a mature contractile apparatus and attach to the scar tissue via newly formed myotendinous junctions. The scar tissue is then retracted, bringing the ends of the regenerated myofibers closer together. The healing process is driven by fibroblasts transforming into contraction-capable myofibroblasts.

How do I help a muscle strain recover?

According to one literature review, recovery from muscle strains should use a short period of immobilization or protection followed by controlled and progressive mobilization. In other words, after a short period (3-6 days) of rest, it’s important to start with light exercises and gradually increase the intensity as your muscle starts to heal. Think of it like slowly turning up the volume on your workout playlist, instead of blasting it at full volume.

One of the best ways to workout with a muscle strain is to engage in low-impact activities. This includes exercises such as walking, cycling, or doing movements that gently activate the muscle without causing too much pain. For example, on a 1-10 pain scale with 10 being the worst, you would want to hover around ~3-5. These activities will help you stay active without putting too much stress on your injured muscles in the first few weeks. It is important to note that exercise should only be done under the guidance of a qualified health care professional. Individuals who are recovering from a muscle strain should begin with Phase 1 (described below) and gradually increase the intensity as the strain begins to heal. It is also important to be careful of activities that could further aggravate the strain, such as running, jumping, and participating in sports.

What can I do to help a muscle strain heal?

Generally, recovery from a muscle strain takes 3 phases:

Phase 1:

Protect, apply ice, and use pain management.

- In the first few days after a muscle strain it’s important to let the pain and inflammation subside while protecting the affected muscle. This may mean 3-6 days of no exercise, while using ice on the affected area 2-3 times per day for 3-5 minutes per day.

- Excessive stretching of the injured area should be avoided, as this can result in dense scar formation in the area of injury, prohibiting muscle regeneration.

- Pain medications, such as acetaminophen are a good option rather than non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen, since some science has indicated NSAIDs may have a lack of benefit and possibly negative effect on muscle function following recovery.

Therapeutic Exercise

- Therapeutic exercises such as isometrics, balance exercise, and slow easy movement of the affected muscle could occur after the first 3-6 days of recovery. The exercises should always be performed without pain, with the intensity of the exercises progressed from light to moderate as tolerated.

Progression to phase 2 can begin once the following criteria are met: normal movement without pain and pain-free isometric contraction using submaximal (50%–70%) isometric resistance during a manual strength test.

Dirty Details on how to perform a isometric manual strength test:

An isometric manual strength test is a type of muscle assessment test where the muscle being tested is held in a stationary position while the individual exerts force against a non-moving object or against a resistance provided by a therapist or examiner. During the test, the muscle is not allowed to shorten or lengthen, it remains at a constant length, this is what is meant by “isometric” contraction. The manual strength test is performed at a submaximal level, meaning that the individual is not exerting the maximum amount of force they are capable of, usually between 50-70% of their maximum voluntary contraction. The purpose of this test is to evaluate the muscle’s strength, endurance, and overall recovery progress in the beginning stages of a muscle strain recovery.

Phase 2:

Range of motion, ice, and pain management

- During phase 2, range of motion should no longer be restricted, because strength without accompanying pain should now be present. However, explosive acceleration movements (e.g, sprinting) could cause re-injury. At this stage you may think your muscle is healed, but it might not be.

- Re-injury rates are high during this phase, especially in athletes.

- Icing for 5-10 minutes should be performed after the rehabilitation exercises, as needed, to help decrease possible associated pain and inflammation.

Therapeutic Exercise

- Exercises used in phase 2 promote a gradual increase in muscle lengthening, compared to the limited range of motion allowed in phase 1. This is based on underlying science that mobilization of muscle 5 to 7 days after injury can enhance muscle regeneration.

Progression to phase 3 can begin once the following criteria are met: low intensity strength training (i.e., 20-40% 1RM) without pain or discomfort.

Phase 3:

Protect, apply ice, and use pain management.

- Muscle should be symptom free of pain

- Use ice for 5-10 minutes post-exercise if needed

- Avoid full intensity exercise if pain, tightness, or stiffness occurs

Therapeutic Exercise

- Therapeutic exercises should include a slow increase in intensity and volume of exercise for the affected muscle back to normal workouts.

- This phase should also address fear and apprehension around using the strained muscle.

How do I workout around a muscle strain?

Another great option is to engage in strength training exercises that don’t put a lot of stress on the affected area. For example, if you strained your hamstring, you can still work on upper body exercises by doing bench press and lat pulldown. This will help you maintain your overall fitness while you rehabilitate your hamstring or even improve one area of your body.

A specialization cycle to catch-up any lagging muscles is something to consider while recovering from a muscle strain – like working on your biceps while your legs are in recovery mode. Another great option is to engage in core exercises and other neglected areas such as your rotator cuffs. These exercises will help to improve stabilizer muscles, which will in turn help to support your injured muscle and help prevent other muscles from becoming imbalanced or injured in the future.

What increases my risk for a muscle strain?

Participating in sports can increase your risk of muscle strains, especially if you haven’t played for a while. Other risk factors include older age, previous muscle injury, lack of strength and flexibility, and over- or under-training. Poor body mechanics when lifting heavy objects or doing everyday activities can also cause muscle strains. For example, you’ve probably heard the phrase “lift with your legs not your back”. Other factors that can predispose an athlete to muscle strain injuries include poor conditioning, inadequate warm-up, poor technique, inadequate rest, and inadequate hydration.

Re-injuries are particularly prevalent during the initial period of return to sports, indicating that there might be a gap between the amount of time required for tissue healing and the tissue’s capability to tolerate strenuous sport-specific loading, so rehabilitation and careful testing prior to playing any sports is important.

How do I reduce my risk for a muscle strain?

To reduce the risk of a muscle strain, people should take preventive measures such as regular stretching and strengthening exercises, proper conditioning, and adequate warm-up and rest.

Citations:

- Aicale R, Tarantino D, Maffulli N. Overuse injuries in sport: a comprehensive overview. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13:309.

- Erickson LN, Sherry MA. Rehabilitation and return to sport after hamstring strain injury. J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6(3):262-270.

- Bayer ML, Magnusson SP, Kjaer M. Early versus delayed rehabilitation after acute muscle injury. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(13):1300-1301.

- Bayer ML, Hoegberget-Kalisz M, Jensen MH, et al. Role of tissue perfusion, muscle strength recovery, and pain in rehabilitation after acute muscle strain injury: A randomized controlled trial comparing early and delayed rehabilitation. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018;28(12):2579-2591.

- Noonan TJ, Garrett WEJ. Muscle strain injury: diagnosis and treatment. JAAOS – Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 1999;7(4):262.

- Järvinen TAH, Järvinen TLN, Kääriäinen M, et al. Muscle injuries: optimising recovery. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21(2):317-331.

- Ramos GA, Arliani GG, Astur DC, Pochini A de C, Ejnisman B, Cohen M. Rehabilitation of hamstring muscle injuries: a literature review. Rev Bras Ortop. 2016;52(1):11-16.

- Lauersen JB, Bertelsen DM, Andersen LB. The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(11):871-877.

- Wong S, Ning A, Lee C, Feeley BT. Return to sport after muscle injury. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015;8(2):168-175.

- Järvinen TA, Järvinen M, Kalimo H. Regeneration of injured skeletal muscle after the injury. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;3(4):337-345.