Welcome to our ultimate guide to antioxidants. This is your go-to resource for everything you need to know about antioxidants. We’ll be starting with the basics, explaining what antioxidants are and what roles they play in our bodies. Following this, we’ll dive deep into the benefits these vital compounds offer, with a special focus on the latest scientific findings. But it’s not just about science – we’ll also guide you towards the best dietary sources of antioxidants and help you understand how much you should consume. From there, we’ll offer practical tips, including examples of antioxidant-rich meals. This guide also addresses important questions about potential overconsumption of antioxidants, advising you on when it’s best to take them, the possible side effects of excess intake, and how to avoid such pitfalls. So whether you’re new to the world of antioxidants or looking to refresh your knowledge, we’re sure you’ll learn something new.

What are antioxidants?

In human physiology, there is a balance between reactive oxidants and antioxidants that is important for maintaining cellular health. Free radicals, including reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and reactive sulfur species (RSS), naturally arise as byproducts of our cellular metabolic processes (Sies 2015). When the production of these reactive oxidants exceeds the body’s capacity to counter them, oxidative stress and cellular damage occur. Antioxidants help protect cells from the damaging effects that can occur because of free radicals.

Effective protection against oxidative stress involves a synergistic relationship between the body’s endogenous and exogenous antioxidant defense systems. Endogenous antioxidant defenses consist of a complex network of enzymes and molecules within our cells that tirelessly combat reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress.

Enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), along with antioxidants like glutathione (GSH) and coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), work together to neutralize free radicals and maintain cellular health. These internal defense mechanisms are complemented by exogenous antioxidant defenses obtained from external sources such as our diet and supplementation.

Antioxidant-rich foods, including fruits, vegetables, nuts, and whole grains, provide a diverse range of exogenous antioxidants like vitamins C and E, carotenoids, flavonoids, and polyphenols. By incorporating these exogenous antioxidants into our daily routines, we strengthen our body’s ability to counter oxidative stress, reducing the risk of cellular damage and promoting overall well-being.

While exogenous sources contribute to our antioxidant defenses, it’s important to note that a balanced and varied diet remains the cornerstone, as it provides a synergistic blend of antioxidants and other beneficial compounds that work together to support optimal health.

What are the benefits of antioxidants?

Antioxidants are substances that can help prevent or slow damage to cells caused by free radicals. They can be found in food and supplements. The following are some purported benefits of antioxidants for general health purposes:

- Decreases risk of Chronic Diseases: Many studies have found a connection between a diet rich in antioxidants and a lower risk of diseases like heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and other chronic diseases (Wang et al., 2014). For example, antioxidants like beta-carotene, selenium, and vitamins C and E may enhance the immune system (Liu 2003; Block et al., 2002).

- Promotes Skin Health: Antioxidants like Vitamin C and E are thought to promote skin health (Pullar et al., 2017; Keen & Hassan 2016). Vitamin A (i.e., retinol) seems to have the most support in the literature for improving/reducing wrinkles and overall skin health (Dattola et al., 2020; Rote & Harrison-Tyron 2021; Kafi et al., 2007).

- Improves Eye Health: Certain antioxidants, such as lutein and zeaxanthin, have been found to be beneficial for eye health. They can help prevent macular degeneration, a leading cause of vision loss in older adults (Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group, 2001).

Antioxidants can also have detrimental effects. For example, a review by Yang et al., (2018) suggested that at high concentrations, many antioxidants could act as pro-oxidants, increasing oxidative stress and inducing toxicity.

Some antioxidants can improve overall health and they may also have a role in enhancing physical exercise and overall fitness. Below are more examples of how antioxidants can potentially support you in those areas:

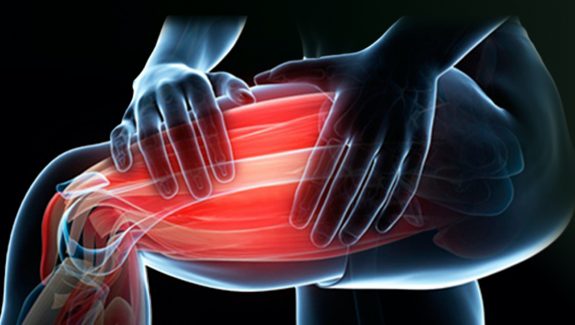

- Exercise Reduces Oxidative Stress: Exercise can cause a transient increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to acute oxidative stress, but chronic exercise can reduce oxidative stress and muscle damage, thus improving recovery if not taken to extremes (Pingitore et al., 2015).

- May Enhance Recovery: Antioxidants such as tart cherry juice can potentially help to reduce muscle damage and inflammation post-exercise, leading to improved recovery times (Kuehl et al., 2010; Vitale 2017).

- May Improve Exercise Performance: A recent meta-analysis of RCTs involving predominantly trained males concluded that polyphenol supplementation (average dose 688 mg/day) for at least 7 days can improve exercise performance by ~1.9% (Somerville et al., 2017).

- Prevents Muscle Damage: There is some evidence that certain antioxidants, such as curcumin, a potent antioxidant found in turmeric, can help to reduce exercise-induced muscle damage and oxidative stress (Takahashi et al., 2014).

While antioxidants are frequently touted for their health benefits, it’s critical to approach the topic with a healthy dose of scientific skepticism. Current research on antioxidants is indeed complex and equivocal, with no universal consensus on their precise benefits or recommended dosages.

Numerous studies have revealed potential benefits of antioxidants, such as protecting against cell damage and combating oxidative stress. However, other studies have failed to conclusively link antioxidant supplementation to significant reductions in the risk of chronic diseases, like heart disease or cancer. Similarly, while dietary guidelines provide recommended daily amounts for specific antioxidant vitamins and minerals, these recommendations are based on preventing deficiencies, not optimizing health or preventing disease.

Furthermore, too much of certain antioxidants can actually be harmful. Therefore, it’s important to approach antioxidants not as a panacea, but as part of a balanced, varied diet and a healthy lifestyle.It’s noteworthy to add that most large observational studies which show health benefits associated with antioxidants focus on the consumption of antioxidant-rich fruits and vegetables, rather than antioxidant supplements. These studies highlight the importance of a whole-foods approach, suggesting that it may be the combination of nutrients in these foods, rather than antioxidants alone, that contributes to these health benefits.

What are the best sources of antioxidants?

A wide array of foods serve as sources of antioxidants, encompassing various fruits, vegetables, nuts, and even certain meats and oils. These foods, when included as part of a balanced diet, offer a diverse assortment of antioxidants that can help to combat oxidative stress and contribute to overall health.

Vitamin C, is a water-soluble antioxidant that is prevalent in fruits and vegetables, such as oranges, strawberries, bell peppers, and broccoli, to name a few (Carr and Maggini, 2017).

Vitamin E, a fat-soluble antioxidant, is typically present in nuts, seeds, and certain greens like spinach, as well as plant-based oils, including sunflower and safflower oil (Jiang et al., 2001). Brightly colored fruits and vegetables like carrots, kale, and sweet potatoes are rich in Beta-Carotene (Stahl and Sies, 2003), while Brazil nuts, seafood, and meats are recognized as good sources of the mineral antioxidant, selenium (Combs, 2001).

Flavonoids are a diverse group of phytonutrients (plant chemicals) found in almost all fruits and vegetables. They are part of the polyphenol family and are categorized by their chemical structure into several classes including flavonols, flavones, flavanones, isoflavones, catechins, anthocyanidins, and chalcones. Flavonoids are found in a variety of foods such as apples, berries, onions, nuts, dark chocolate, and beverages like tea and wine (Manach et al., 2004).

Curcumin, a potent antioxidant, is found in turmeric, a spice commonly used in curry dishes (Menon and Sudheer, 2007). Lycopene is found in high quantities in tomatoes and tomato products, watermelon, and pink grapefruit (Rao and Rao, 2007). It’s important to maintain a balanced diet rich in these food sources for a comprehensive intake of different antioxidants. While supplements can provide antioxidants, obtaining them from whole foods is preferred because of the combined interaction of different antioxidants and other beneficial nutrients present in these foods.

How much antioxidants do I need?

Determining the precise daily need for antioxidants is challenging, as requirements can vary based on factors like age, sex, lifestyle, and overall health. However, certain antioxidant nutrients do have established recommended daily allowances (RDAs) set by health organizations. Here are some examples:

- Vitamin C: The RDA for men is 90 milligrams per day, and for women, it’s 75 milligrams per day, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

- Vitamin E: The RDA for adults is 15 milligrams (or approximately 22.4 International Units) per day, according to the NIH.

- Selenium: The RDA for adults is 55 micrograms per day, according to the NIH.

For other antioxidants such as flavonoids, specific RDAs haven’t been established due to the variability in types and content in food sources, and the complexity of their metabolism and bioavailability. Remember, these RDAs are the minimum you need to consume per day to not be deficient, so if you aren’t hitting these numbers with your diet it is a good opportunity to take a close look at your diet or use supplements to increase your intake.

What’s an example of a meal with antioxidants?

In terms of food intake, a diet that includes a variety of fruits and vegetables (5 servings or more per day), whole grains, nuts and seeds can provide a good range of different antioxidants. While taking antioxidant supplements can help ensure you meet these requirements, it’s generally better to obtain antioxidants from whole food sources, which provide a combination of antioxidants that work together, along with other beneficial nutrients.

Here are two basic examples of meals that would provide good sources of antioxidants:

Meal 1: Grilled Chicken Salad with Berries and Nuts

Ingredients:

- 120g grilled chicken breast (approx. 28g protein)

- 2 cups mixed salad greens (negligible macros, but packed with vitamins and minerals)

- 1 cup mixed berries (blueberries, strawberries, raspberries – approx. 20g carbs)

- 28g almonds (approx. 6g protein, 15g fat, 6g carbs)

- Dressing made with 1 tbsp olive oil and lemon juice (approx. 14g fat)

Macronutrient breakdown:

- Protein: ~34g

- Fat: ~29g

- Carbohydrates: ~26g

Micronutrient breakdown:

- High in Vitamin C, E, fiber, and antioxidants from the mixed berries and salad greens.

- Provides healthy fats, Vitamin E, and additional antioxidants from almonds and olive oil.

Meal 2: Salmon with Quinoa and Steamed Broccoli

Ingredients:

- 100g salmon filet (approx. 22g protein, 13g fat)

- 1 cup cooked quinoa (approx. 8g protein, 5g fat, 39g carbs)

- 1 cup steamed broccoli (approx. 2.5g protein, 6g carbs, rich in antioxidants, Vitamins C, E, K, and fiber)

Macronutrient breakdown:

- Protein: ~32.5g

- Fat: ~18g

- Carbohydrates: ~45g

Micronutrient breakdown:

- Salmon is high in omega-3 fatty acids, B vitamins, and the antioxidant selenium.

- Quinoa is a great source of fiber, minerals, and antioxidants.

- Broccoli is high in fiber, Vitamins C, K, and various antioxidants

| Want some more recipes? Check out our free-recipe ebook, 101-Macro Friendly Meals |

Can I take too many antioxidants?

It is possible to get too much of certain antioxidants, particularly through supplementation, which can potentially lead to harmful effects. For instance, high doses of vitamin E can increase the risk of bleeding by reducing the ability of the blood to form clots. A meta-analysis of clinical trials found that high-dosage (≥400 IU/day) vitamin E supplements may increase the risk of death and should be avoided (Miller et al., 2005).

Excess intake of vitamin A can lead to nausea, dizziness, and even hair loss. Very high doses can be fatal. A study has shown that an intake above the tolerable upper intake level of 3000 μg/day may increase the risk of osteoporosis (Penniston and Tanumihardjo, 2006).

In a Cochrane Review, researchers looked at data from 78 different studies, which included nearly 300,000 people. They focused on four types of antioxidants—beta-carotene, vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium—and compared the outcomes to people who didn’t take any supplements. The results were a bit mixed. In studies that were very well conducted, the researchers didn’t see any major effect of the antioxidants on lifespan. But when they looked at all the studies together, it seemed like beta-carotene, vitamin A, and vitamin E might actually increase the risk of death. Vitamin C and selenium didn’t seem to change anything. The researchers concluded that, based on their findings, they couldn’t really recommend antioxidant supplements to help people live longer (Bjelakovic et al., 2012).

Seeing the above examples, it’s important to not have the mindset that “more is better” when approaching antioxidants.

When should I take antioxidants?

The use of antioxidant supplements can be considered in the following scenarios:

- Nutrient Deficiencies: If a person’s diet is not providing enough antioxidant-rich foods due to factors such as food allergies, dietary restrictions, or limited access to fresh fruits and vegetables, they may benefit from antioxidant supplements. A healthcare provider can help determine if you have a nutrient deficiency.

- Certain Health Conditions: Some health conditions can increase a person’s need for certain antioxidants. For example, people with cystic fibrosis often need to take supplemental fat-soluble vitamins, including antioxidants like vitamins A and E, because their bodies have trouble absorbing these nutrients from food.

- High Oxidative Stress Levels: Individuals exposed to high levels of oxidative stress, such as smokers or those frequently exposed to pollution, may benefit from additional antioxidants. However, this should ideally be addressed by reducing the exposure to oxidative stress.

- Aging: As people age, their bodies may not absorb nutrients as efficiently, and the risk of chronic diseases increases. Some studies suggest that antioxidant supplements might help delay the effects of aging or reduce the risk of age-related diseases, although the evidence is mixed.

- High Levels of Physical Activity: Intense or prolonged physical activity can increase oxidative stress. Some athletes or those engaged in high levels of physical activity might consider antioxidant supplementation, although it’s worth noting that the relationship between exercise, oxidative stress, and antioxidant supplementation is complex and not fully understood

What are the side effects of antioxidants?

While the beneficial effects of antioxidants in maintaining health and preventing diseases are somewhat established, it’s crucial to understand that these compounds can be a double-edged sword. When consumed in appropriate amounts, they are generally safe and provide a variety of health benefits. However, the overconsumption of antioxidants, especially through supplements, can lead to potential side effects and health risks, which vary depending on the specific antioxidant.

Take vitamin A, for instance. It’s vital for maintaining healthy vision, skin, and immune function, but when consumed excessively, it can induce symptoms such as nausea and dizziness, and in extreme cases, it may even lead to a coma or death. Chronic intake of high amounts of vitamin A has also been associated with hair loss and bone thinning, as suggested by Penniston & Tanumihardjo’s study in 2006.

Vitamin C is another case in point. It’s an essential nutrient known for its role in immune function and collagen synthesis. Although it’s generally well-tolerated, taking high doses of vitamin C – greater than 2,000 milligrams per day – can cause issues such as diarrhea, nausea, stomach cramps, and even kidney stones, as per the National Institutes of Health (2021).

Similarly, vitamin E is a potent antioxidant that protects the body’s cells from damage. But high doses of vitamin E might increase the risk of bleeding by inhibiting blood clotting. There are also concerns that prolonged intake of high doses of vitamin E could potentially reduce bone mineral density, according to the National Institutes of Health (2021).

Beta-carotene, which the body converts into vitamin A, illustrates the potential risks of antioxidants specifically for certain groups of people. A 2010 study by Druesne-Pecollo and colleagues found that in smokers and people who have been exposed to asbestos, supplements containing beta-carotene might increase the risk of lung cancer.

Lastly, consider selenium, an essential mineral with antioxidant properties. While it’s necessary for thyroid function and DNA synthesis, high selenium intake can lead to a condition called selenosis. Symptoms of selenosis can range from gastrointestinal upset, hair loss, and white blotchy nails, to garlic breath odor, fatigue, irritability, and even mild nerve damage, as stated by the National Institutes of Health (2021).

In conclusion, while antioxidants are a critical component of a healthy diet, they should be consumed with care and moderation. The overconsumption of these nutrients can potentially lead to adverse health effects, emphasizing the importance of balanced, moderate intake, ideally through a diverse diet.

What is the best timing for antioxidant intake?

The optimal time for antioxidant intake largely hinges on their form of consumption. For antioxidants derived from food sources, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and seeds, they can be consumed throughout the day as part of your normal meals and snacks. This approach assists in maintaining consistent antioxidant levels to combat oxidative stress as and when it occurs.

If you’re taking antioxidant supplements, the timing can be contingent on the specific supplement in question. For instance, some are better absorbed when taken alongside meals, particularly those that are fat-soluble, like vitamins A, D, E, and K. Other supplements may have specific timings recommended due to their interactions with other nutrients or medications. Therefore, you should generally follow the instructions provided by the supplement manufacturer or your healthcare provider.

References:

- Sies H. (2015). Oxidative stress: a concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox biology, 4, 180–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2015.01.002

- Wang X, Ouyang Y, Liu J, et al. (2014). Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 349, g4490. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g4490

- Liu RH. (2003). Health benefits of fruit and vegetables are from additive and synergistic combinations of phytochemicals. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 78(3), 517S-520S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/78.3.517S

- Pullar, J. M., Carr, A. C., & Vissers, M. C. (2017). The Roles of Vitamin C in Skin Health. Nutrients, 9(8), 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9080866

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. (2001). A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960), 119(10), 1417–1436. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417

- Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C. (2012). Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2012(3), CD007176. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007176.pub2

- Takahashi, M., Suzuki, K., Kim, H. K., Otsuka, Y., Imaizumi, A., Miyashita, M., & Sakamoto, S. (2014). Effects of curcumin supplementation on exercise-induced oxidative stress in humans. International journal of sports medicine, 35(6), 469–475. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1357185

- Peternelj, T. T., & Coombes, J. S. (2011). Antioxidant supplementation during exercise training: beneficial or detrimental? Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 41(12), 1043–1069. https://doi.org/10.2165/11594400-000000000-00000

- Carr, A. C., & Maggini, S. (2017). Vitamin C and immune function. Nutrients, 9(11), 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9111211

- Jiang, Q., Christen, S., Shigenaga, M. K., & Ames, B. N. (2001). Gamma-tocopherol, the major form of vitamin E in the US diet, deserves more attention. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 74(6), 714–722. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/74.6.714

- Stahl, W., & Sies, H. (2003). Bioactivity and protective effects of natural carotenoids. Biochimica et biophysica acta, 1740(2), 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.12.006

- Combs, G. F. (2001). Selenium in global food systems. The British journal of nutrition, 85(5), 517–547. https://doi.org/10.1079/BJN2000280

- Manach, C., Scalbert, A., Morand, C., Rémésy, C., & Jiménez, L. (2004). Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 79(5), 727–747. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727

- Menon, V. P., & Sudheer, A. R. (2007). Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 595, 105–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_3

- Rao, A. V., & Rao, L. G. (2007). Carotenoids and human health. Pharmacological research, 55(3), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2007.01.012

- Pandey, K. B., & Rizvi, S. I. (2009). Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2(5), 270–278. https://doi.org/10.4161/oxim.2.5.9498

- Cushnie, T. P., & Lamb, A. J. (2011). Recent advances in understanding the antibacterial properties of flavonoids. International journal of antimicrobial agents, 38(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.02.014

- Kumar, S., & Pandey, A. K. (2013). Chemistry and biological activities of flavonoids: an overview. TheScientificWorldJournal, 2013, 162750. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/162750

- Miller, E. R., Pastor-Barriuso, R., Dalal, D., Riemersma, R. A., Appel, L. J., & Guallar, E. (2005). Meta-analysis: high-dosage vitamin E supplementation may increase all-cause mortality. Annals of internal medicine, 142(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-142-1-200501040-00110

- Penniston, K. L., & Tanumihardjo, S. A. (2006). The acute and chronic toxic effects of vitamin A. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 83(2), 191–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/83.2.191

- Bjelakovic, G., Nikolova, D., Gluud, L. L., Simonetti, R. G., & Gluud, C. (2012). Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (3). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007176.pub2

- Penniston, K. L., & Tanumihardjo, S. A. (2006). The acute and chronic toxic effects of vitamin A. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 83(2), 191–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/83.2.191

- National Institutes of Health. (2021). Vitamin C. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminC-HealthProfessional/

- National Institutes of Health. (2021). Vitamin E. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminE-HealthProfessional/

- Druesne-Pecollo, N., Latino-Martel, P., Norat, T., Barrandon, E., Bertrais, S., Galan, P., & Hercberg, S. (2010). Beta-carotene supplementation and cancer risk: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. International journal of cancer, 127(1), 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.25008

- National Institutes of Health. (2021). Selenium. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Selenium-HealthProfessional/