Is Flexible or Rigid Dieting Better For Weight Loss?

People who use a flexible diet focus on the overall calories and macronutrients while manipulating food choices to meet their nutrition goals. For example, they may use different types of fruits, vegetables, and grains throughout the week. They may also adapt to social situations by having the flexibility to dine at a restaurant or have a few alcoholic beverages with friends. On the other hand, rigid dieters generally stick to a strict set of foods or a meal plan, sometimes creating a “no-go” list so they do not consume highly satiable, calorie dense foods such as cookies and cake. Flexible dieting has been touted as the best way to lose fat and keep it off, while rigid dieting, which is focused on dietary restraint, has been linked to eating disorders.

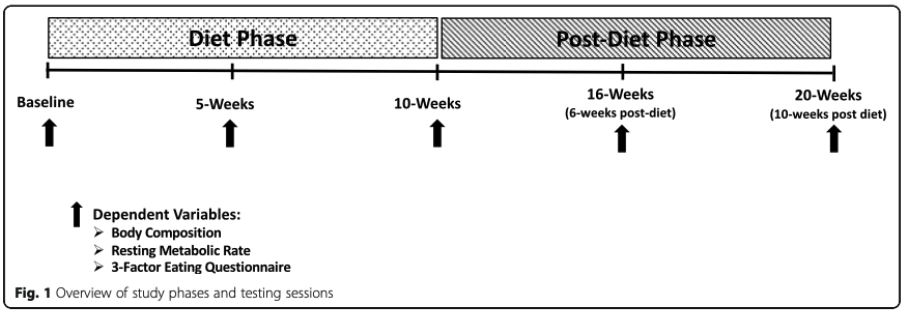

A recent study by Conlin et al., compared rigid vs flexible dieting in a group of young resistance-trained adults (age ~25) who dieted for 10 weeks and then completed a 10-week post-diet weight maintenance phase.

Figure 1. Overview of study design. Image from Conlin et al., 2021

After a three day run-in period to determine maintenance calories, participants were placed on a diet that lowered their calories by 25%, were matched according to fat mass, and randomly assigned to a flexible (FLEX) or rigid (RIGID) diet plan. Participants were told to eat 2 g/kg of and split their remaining calories evenly between fat and carbohydrate. The RIGID dieting group was given an individualized set meal plan and were instructed to only eat foods that were on their meal plan. The meal plan consisted of eggs, fruit, chicken breast, greek yogurt, lean ground beef, and nuts. The diet was fairly diverse in both nutrients and foods (see Table 1 in manuscript) while also being practical. The FLEX group was provided an ebook on flexible dieting and were given macronutrient goals.

The authors found no significant difference in bodyweight between the groups during the weight loss phase (FLEX = -2.6kg, RIGID = -3.0kg). They also found no differences in fat mass loss or decrease in body fat percentage between groups. At the end of the study, the caloric restriction for both groups was less than the desired 25% (FLEX = -20% and RIGID = -17.7%) but still reasonable. Interestingly, during the post-diet phase, a significant effect was observed for fat free mass (FFM) with the FLEX group gaining a greater amount of FFM (+1.7 kg) in comparison with the RIGID group (−0.7 kg). Since fat mass did not change during this period, this indicates the FLEX group may have somehow gained FFM or restored glycogen they lost during the diet. The authors also used the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) to analyze cognitive restraint, disinhibition, and hunger in participants during the study. The whole idea behind flexible dieting is that it should provide less cognitive restraint for people who use it. However, the TFEQ results indicated no differences in any component between groups. This means that the dieting nor weight maintenance phases influenced how people felt about eating.

This is one of the first studies on rigid vs flexible dieting in a young healthy population, and thus there are a large number of issues, but the main one is the interpretation of the data. The authors claim that “A flexible or rigid diet strategy is equally effective for weight loss during a caloric restriction diet” yet they would need to do completely different statistical tests to determine if this were true. Namely, they would need equivalence testing, because in science ”no difference” does not mean equivalence. Another issue is the analysis of per-protocol vs intent to treat (ITT) which means they only analyzed the people who adhered to the FLEX and RIGID diets. Since more people did not adhere (11 of 20 analyzed (55%)) to the FLEX diet compared to the RIGID diet (12 of 19 analyzed (63%)), it could mean that it is more difficult to adhere to a flexible diet. Additionally, there was a substantial difference in aerobic exercise between groups, where the RIGID group completed twice the amount as the FLEX group. Ultimately, this study was a good attempt at comparing rigid vs flexible dieting, and gives us a little more insight into how the two compare; however, we need a lot more research to determine which one is superior or if they’re equivalent.

Flexible dieting is sometimes referred to as “if it fits your macros” (IIFYM), which is a macronutrient-based dieting system that focuses on monitoring individual macronutrient intake, with less regard for the specific foods consumed. In IIFYM, no foods are “off-limits” as long as certain daily macronutrient targets are met. The main disadvantage for flexible and IIFYM dieting is the potential for people to opt for “empty” calories rather than nutrient-dense foods, thus they may be consuming too few micronutrients or insufficient fiber. Data from a previous study on bodybuilders somewhat supports this idea because there were higher levels of vitamin E, K, and C in those who were flexible/IIFYM dieters compared to rigid dieters.

If we take all of the current literature together and think about flexible vs rigid dieting, we should mainly consider the potential beneficial mental aspects because given the same caloric deficit, we should see the same results in body weight and fat mass loss, especially if a high protein diet and resistance training are also used.