Research Review #10

Brandon Roberts, Ph.D., CSCS*D

Chief Science Officer

*Note from Brandon: if you want to learn how to interpret research go read each study before reading the breakdown below, take notes, then compare your interpretation to mine.

Study #1

Title: Continuous versus Intermittent Dieting for Fat Loss and Fat-free Mass Retention in Resistance-trained Adults: The ICECAP Trial

Question: Can intermittent energy restriction (IER) improve fat loss and fat-free mass retention compared with continuous energy restriction (CER) in resistance-trained adults?

Why

Diet breaks can help coaches and athletes by giving them an alternative to continuous caloric restriction. Surprisingly, one of the first studies on diet breaks was what scientists call a “happy accident” because it was designed to determine if weight loss relapses could be induced by intentionally interrupting the momentum of weight loss and thus provide a model for weight maintenance research. As you may have guessed ⸺ that didn’t work. Instead, the researchers found that there were no differences in body weight between those who had no diet breaks, 2-week breaks, or 6-week breaks over 20 weeks of dieting. Interestingly, the diet break groups had lower adherence the first week coming back from their break, which flew under the radar of most researchers and could be important for those who need to strictly adhere to reach their goals on time.

If we fast-forward to the current study under review, the focus has now shifted from body weight loss to body composition. This is because we want to maintain fat-free mass (a surrogate for muscle mass) while decreasing fat mass. A recent study by Campbell et al., which we covered on the TCM blog suggested that diets with refeeds, consisting of two days at maintenance calories on the weekends, might help retain fat-free mass. This stirred up some great scientific discussion as the authors went back and forth in letters to the editor with the researchers of the current study.

The goal of the ICECAP (Intermittent versus Continuous Energy restriction Compared in a resistance-trained Adult Population, Jackson Peos et. al.) trial was to determine if intermittent energy restriction (mIER) would help retain fat-free mass and result in greater fat mass loss than continuous energy restriction (mCER). The authors primary hypothesis was that compared with mCER, mIER will result in greater FM loss, with equivalent or greater retention of FFM, in adult athletes at the end of 12 weeks of energy restriction. The secondary hypotheses were that athletes undergoing mIER will have greater retention of muscle performance, physical activity and REE, less drive to eat, better mood and will find the diet more acceptable than mCER.

Who

61 participants recruited. 29 (47.5%) were male and 32 (52.5%) were female. Participants had a mean age of 28.7 years, an average weight of 77.2 kg, and an average body fat percentage of 25.5%, with about ~22% in men and 30% in women. Additionally, most (90.2%) of the participants were engaged in competitive sports.

Study Details

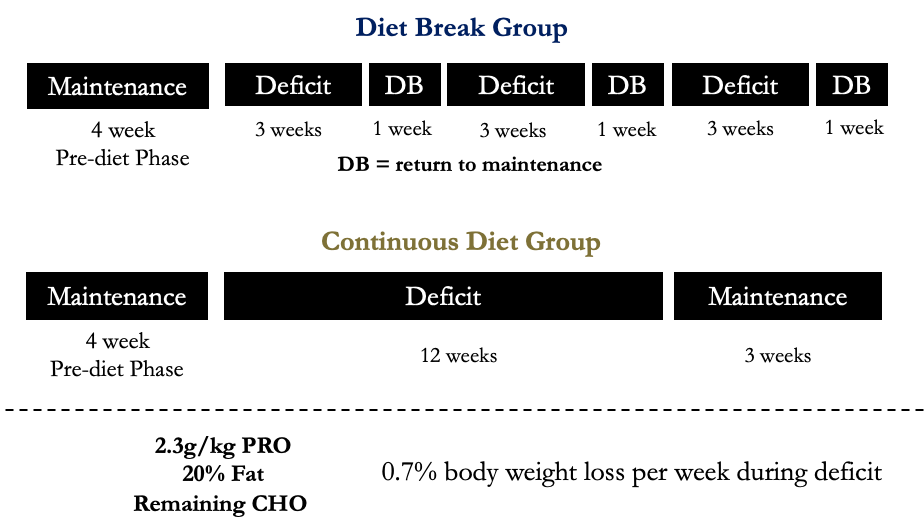

A single-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial with a 1:1 allocation ratio was used. Athletes were randomised to an intervention of either moderate CER (mCER) or moderate IER (mIER). Both interventions consist of 12 weeks of moderate energy restriction (ER), plus 3 weeks in energy balance (EB). The mCER intervention had 12 weeks of continuous moderate ER, followed by 3 weeks in EB. The mIER intervention will entail 12 weeks of moderate ER, administered as 4×3 week blocks of moderate ER, interspersed with 3×1 week blocks of EB.

The weekly body weight loss target was 0.7% based on previous research in athletes which is also within my recommendations for physique athletes (< 1% bw/week).

Participants were told to consume 2.3 g of protein per kg of absolute body mass daily, and 20% of energy intake was allocated to dietary fat, with the remaining energy intake allocated to carbohydrate.

Figure 1. Experimental Design

Outcome measures included: body weight, fat mass, fat-free mass, hormones, performance, and measures of appetite.

Results

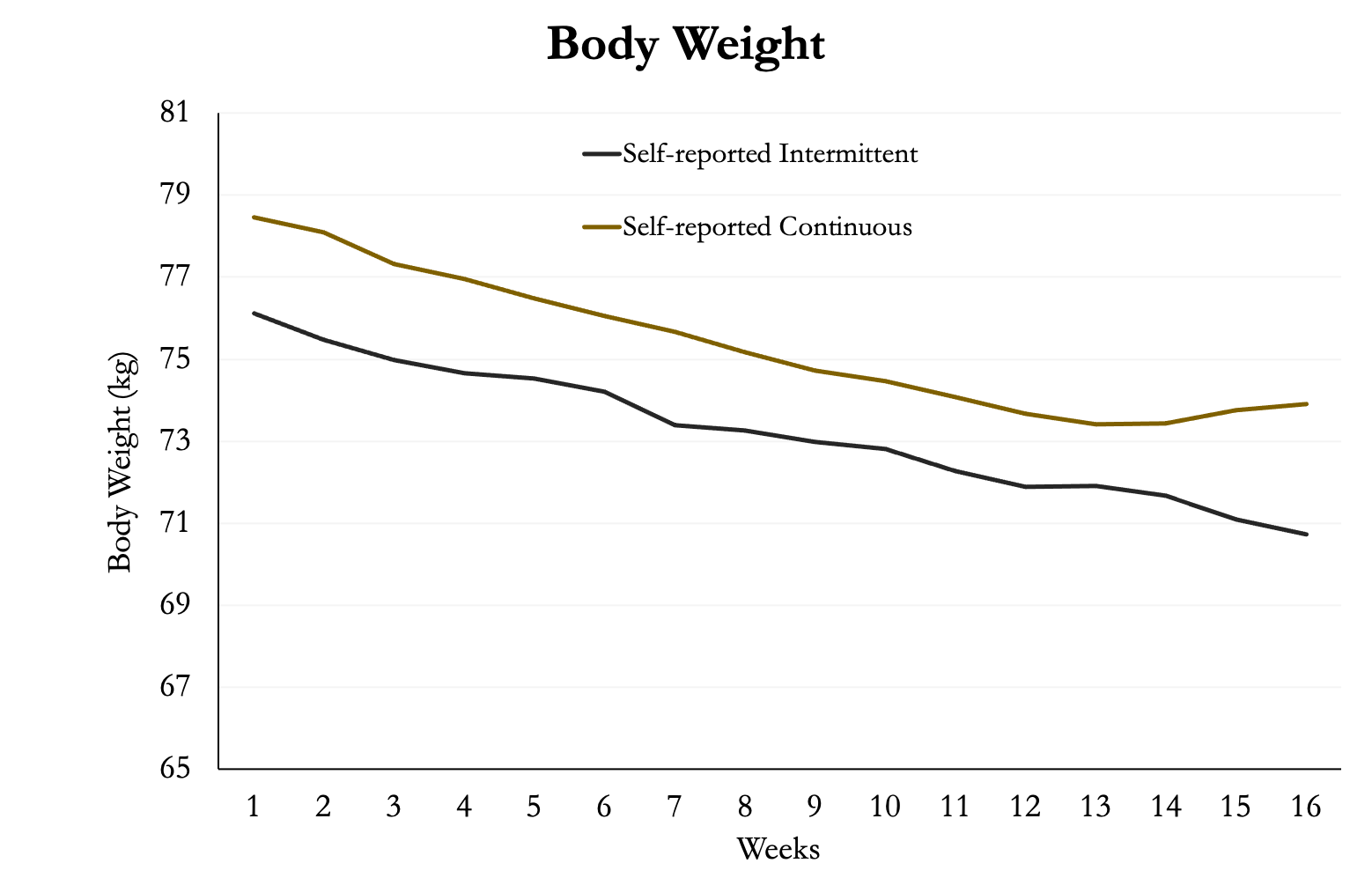

Much like you would do during a deficit, the participants tracked their weight during the study. As you can see in figure 2, there were no significant differences between the two groups. They both declined at a very similar rate. However, the continuous group started at a slightly higher body weight. During the last three weeks of the continuous diet the group returned to eating at the predicted weight maintenance, which is reflected by their body weight rising a small amount (likely due to glycogen).

Figure 2. Body Weight

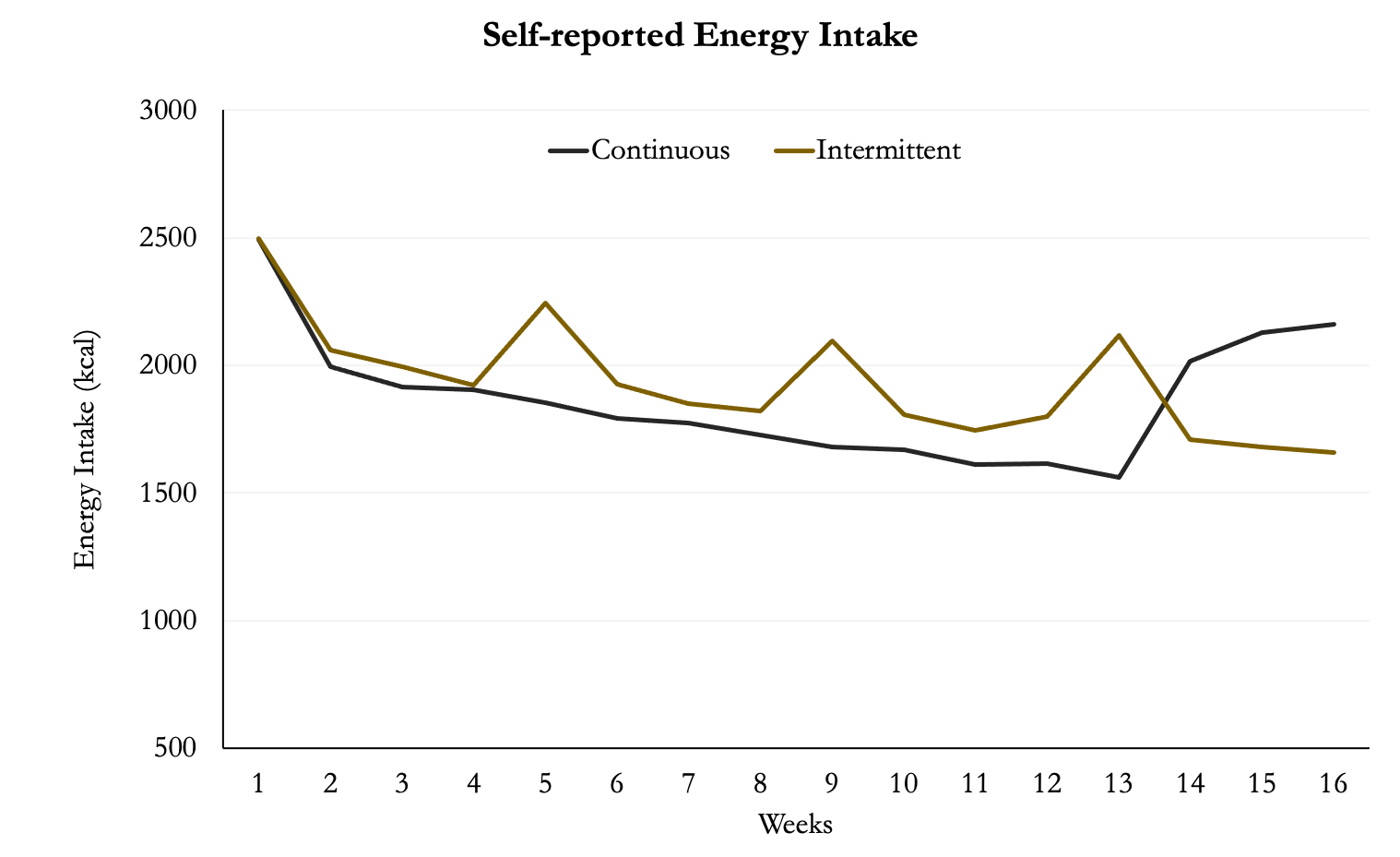

The participants also recorded their energy intake across the trial. It’s very clear where the diet break group had weeks of elevated energy intake. You can also see where the continuous group had elevated intake during the last three weeks where they were eating at predicted maintenance calories.

Figure 3. Energy Intake

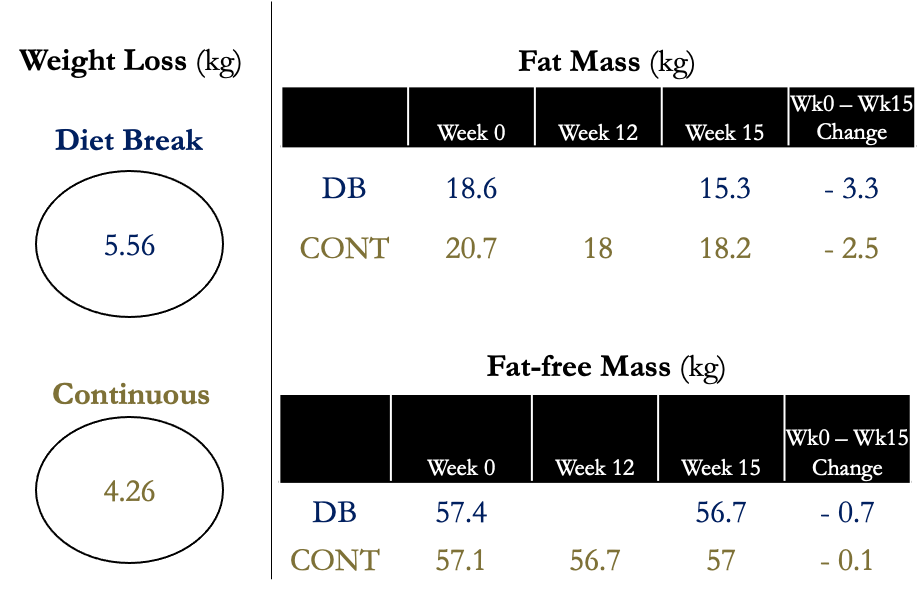

There were no significant differences between groups in fat mass or fat-free mass after 12 weeks of energy restriction, nor was there a difference when accounting for the extra 3 weeks at the end or the study where the continuous group was at maintenance.

Figure 4. Body Composition

Even when comparing per-protocol analysis, which accounts for only the people who strictly adhered and completed all testing requirements, there were still no differences in fat or fat-free mass between groups.

There were no differences between groups in muscle strength or endurance or in resting energy expenditure, testosterone, insulin-like growth factor-1, free 3,3′,5-triiodothyronine (T3) or active ghrelin, nor in sleep, muscle dysmorphia or eating disorder behaviours.

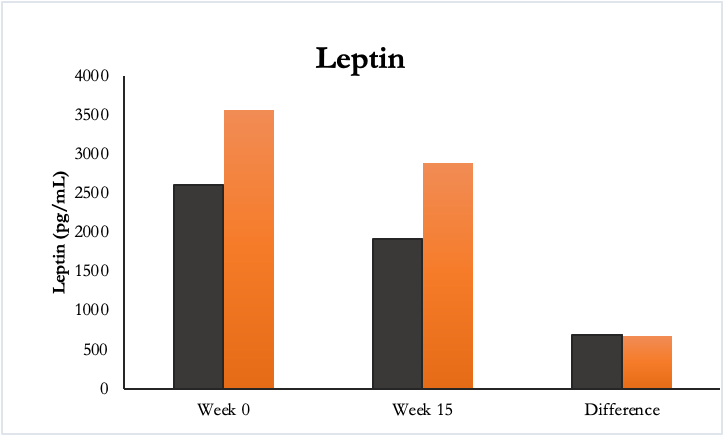

Figure 5. Leptin

Participants in the diet break group experienced significantly less drive to eat than those in mCER after 12 weeks of energy restriction, as indicated by significantly lower measures of hunger and desire to eat, as well as significantly greater measures of satisfaction.

Author’s Answer

“This study shows that in resistance-trained adults, intermittent energy restriction delivered as alternating 3-week periods of moderate energy restriction and 1-week diet breaks (, mIER) for a total of 15 weeks (12 weeks in energy restriction), does not result in lower fat mass or greater fat-free mass compared to 12 weeks of continuous moderate energy restriction (mCER). Participants in the mIER group did however achieve a 1.3-kg lower weight than those in the mCER group when both groups were compared at the end of 15 weeks. This magnitude of weight difference could be practically significant for trained adults involved in weight class sports (eg, boxing, powerlifting), but not for most resistance-trained adults who are usually primarily concerned with the composition of weight loss (ie, loss of fat mass with concomitant retention of fat-free mass) as opposed to absolute weight loss (7).”

My Answer

One of the main reasons to give people a break from dieting is because it’s hard. The problem is that most people don’t want to stop dieting. They want to get it over with. I don’t blame them, especially if you have a lot of weight to lose. The only problem with that is when people try to white-knuckle their way through it then it’s not sustainable. Therefore, if we can use diet breaks or refeeds or some other dieting method to make it easier then maybe we can help people reach their goals.

In the MATADOR (Minimising Adaptive Thermogenesis And Deactivating Obesity Rebound) study, diet breaks were thought to help rescue the drop in resting energy expenditure that occurs with dieting (aka metabolic adaptation). This study used 2 weeks of dieting (33% deficit) alternated with 2 weeks at energy balance compared to continuous dieting. The diet break group had greater weight loss and a tendency for greater fat loss, without greater loss of fat-free mass, than an equivalent time of continuous ER. In addition, despite greater weight loss, there was a smaller reduction in REE (adjusted for changes in FM and FFM) in the diet break group than in the continuous deficit group, consistent with reductions of metabolic adaptation. Furthermore, although both groups regained weight post-intervention, weight loss (reduction from baseline) was, on average, 8.1 kg greater in the diet break group than continuous group at the 6-month follow-up. This data would indicate that diet breaks of 2 weeks alternating with 2 weeks of dieting can improve weight loss and help people maintain their weight. One aspect not mentioned in the study was that diet breaks also allow people to learn how to eat at maintenance, which is what they’ll have to do after their diet.

A somewhat related study was done by Campbell et al., on refeeds that we covered on the podcast and in a blog. Two groups were dieting at a 25% deficit for 7 weeks. One of the groups returned to maintenance calories on the weekends (refeed group) while the other did not. Ultimately, the refeed group lost slightly more fat mass (0.5kg) though it was not statistically significant. There was also a slightly better retention of fat-free mass in the refeed group (0.9kg) although it too was not significant. This and the MATADOR study suggest that giving people some sort of break between 2-14 days could be beneficial, or at worst, not detrimental.

The ICECAP trial did a few things really well. First, it gave people adequate protein (2.3g/kg) which is suggested to be beneficial when in a deficit. Second, the participants lost weight at a reasonable rate thus the diet breaks might not have made as much of a difference than if they had to use a large deficit like the previous two studies mentioned. They also had their diets adjusted if they weren’t meeting the 0.7% criteria. For reference, we recommended losing <0.5% per week or less for physique athletes. Third, the researchers had four weeks of pre-dieting maintenance to make sure the participants weren’t gaining or losing weight. They used the maintenance calories as the number of calories the participants consumed during their diet break. As the diet break group lost weight this likely meant they were eating more than their actual maintenance but still achieving the same results as the continuous diet group. That could explain why the diet break group was more satiated and less hungry than the continuous group.

The ICECAP trial was a well-designed study in an applicable population that adds to our knowledge on the use of diet breaks. It accounted for a lot of factors as much as it could. One limitation the authors admit is that they don’t have great physical activity data. We know that some people move less when they diet, but it would’ve been nice if this could have been quantified in the full cohorts. Furthermore, the participants were also required to expect that their training regimen would be consistent during the dietary weight loss intervention, but there was no data provided on what they were doing. Randomization to one of the two groups should account for that, but to be sure we would either want to give everyone a standardized training program, or collect data on the one they are already doing.

How can we apply this?

For some people, dieting affects a lot of life aspects. It could be because they get hangry. It could be they can’t function on low energy. It could be they have a lot of other stress in their life. The reason doesn’t really matter because we can’t (as coaches/athletes) control everything in our lives. Diet breaks are an opportunity to give the body a break from being in a deficit. They’re useful for vacations, work stress, or anything else.

What’s next?

We still need another diet break study or two so we can figure out all the details. Specifically, does the length of the break matter? Can we use 3-5 days instead of 7 so that we don’t have to diet as long? Is there something that happens around the 2-week mark like we saw in the MATADOR study, or is resistance training and dieting slow enough to maintain our metabolic rate?