The Volume Landmarks

The optimal amount of volume is going to be somewhere between the maximum adaptive volume and the maximum recoverable volume. These two terms are 2 of 4 that have allowed us to assess and prescribe amounts of training volume inside programming for different individuals. These terms are:

-

MV = Maintenance Volume

- The amount of volume required to simply maintain the level of strength and amount of muscle tissue you currently possess.

-

MEV = Minimum Effective Volume

- The amount of volume that becomes stimulative and effective for growing new muscle tissue; this is our minimum effective dose.

-

MAV = Maximum Adaptive Volume

- The amount of volume where stimulus becomes substantial and extremely productive.

-

MRV = Maximum Recoverable Volume

- The amount of volume that is the most stimulative and productive, but most difficult to recover from consistently over time.

To see how this fits into a complete transformation system, check out our [Ultimate Guide to Online Fitness & Nutrition Coaching].

And if you’re the type that likes to dive deep into these theoretical program design frameworks, you can learn more about this exact concept and get a much more in depth explanation of each of the volume landmarks from Dr. Mike Israetel’s Volume Landmarks of Hypertrophy, from the Renaissance Periodization blog. Mike Israetel coined the term and created the entire theory and it’s a great resource for people to use when they start programming and are looking to really progress their training over time.

In fact, because I believe it’s such a useful theory and because Mike is likely the leading expert on muscle hypertrophy, I’ve done a podcast with him to explain further:

How Much Training Volume Do YOU Need?

Now, I believe, based on what we know inside the research AND my own practical experience working with thousands of individuals over the years, that the amount of volume which is optimal for muscle growth is on a sliding scale. It’s going to shift from the most you can do while still managing to recover adequately (MAV; Maximum Adaptive Volume) to the absolute most you can handle while still, but barely, managing to recover (MRV; Maximum Recoverable Volume). This would also require some form of deloading periodized in, which would be a lower volume period after each cycle between these two other periods (MAV, into MRV, followed my MV – i.e. Maintenance Volume, to deload).

I look at it as a sliding scale because there are points where you NEED to push the threshold a bit and see what’s possible, as well as push your body to a place where a deload is required and therefore potentially super-compensate or at least resensitize to a higher volume stimulus, before jumping back into the repetitive cycle. Now, if you constantly push that threshold or stay in your MRV for too long, you’ll likely burnout and be more likely to get injured in the gym.

There are even some studies that have used an ultra high amount of weekly training volume, between 30 to 40 sets per muscle group per week, showing it to be MORE advantageous for muscle growth. However, that amount of volume in a practical, real world, setting is not only hard to adhere to for most people but it’s also not feasible for some people to recover from.

The problem with some of these ultra-high volume studies is that they often use 3 exercises. Such as a bench press, lat pulldown, and leg press — NOTHING else — and seeing what’s better for growth, 20 vs. 40 sets per week. 40 is going to win because it’s actually feasible, since there are no other exercises interfering with recovery.

Now you might be thinking,

That’s still a lot of volume for each of those muscle groups, so how do they recover individually?

Well, a big piece of being able to recover is not just about the localized fatigue (direct to the muscle), but also about the global and systemic fatigue. This just means total energy given, work done, and central nervous system fatigue accumulated from the overall training. When we do 20 sets for 3 muscles vs. 20 sets for all muscles, it’s a difference between 60 and 200+. So as you can imagine, total systemic fatigue will be much greater when the 20 sets is applied across the board — which limits our body’s ability to fully recover.

So although studies like this do show us more is better, in terms of volume and hypertrophy, it doesn’t show us how to practically apply it.

So what the landmarks provide us with, is a tool that gives us a scientific range of volume. What amount we need to maintain muscle, what we at least need to grow a little, what is the optimal range to stay in the majority of the time, and what’s the absolute most we can recover from, temporarily.

Volume Progressions: Do Your Volume Needs Increase Overtime?

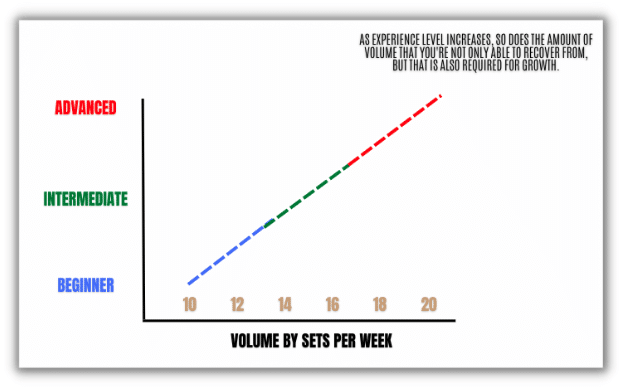

I think the answer to this very commonly asked question is undoubtedly yes, they do. Because anything you do repeatedly over time will cause adaptations to occur and when they do, your body will require more of that same stimulus in order to continue adapting at a favorable rate.

This process isn’t a fast process, though — muscle growth is slow and so is progression as you become more and more advanced, beyond your newbie gains (first 1-3 years) in the gym. So I do not recommend going beyond these landmarks too quickly.

In fact, recent research on volume has progressed in such a way that allowed us to see that training volumes are actually quite individual and are not as black and white as we once believed.

Early research showed “20 sets per week outperformed 10 sets per week of training volume for muscle hypertrophy”… but that began to beg the question of what those participants were doing prior to the study? Meaning, did they go from 0 to 20? Or were they doing 20 prior to going into the study, making the groups of 10 sets per week actually experience a drop in total volume while the other group continued to maintain current volume?

Later on researchers began to control for this and a study emerged that showed it was not a one size fits all, but rather a percentage increase in total weekly volume that made the biggest difference. Which is great, because if you’re just starting out and only doing 5 sets per week – you should jump to 8, not 18! You will have better recovery, and therefore adaptations, and will be less likely to get injured. This also leaves you room to grow, so that when you eventually plateau you can make another small jump from 8 to 12, for example.

Assessing and Prescribing Training Volume

The first step in determining how much training volume YOU specifically need, is to get a log book and see what you’re currently doing. This means whether you’re following your own training plan, working with a plan inside the Tailored Trainer App, or following some other program you found online — you’ll need to count your total sets per muscle group-per week, first. Once you have this number, you can begin increasing the total number of sets performed each week (assuming you’re not building muscle at the current amount of volume being done).

For more generic guidelines on prescribing volume for lifters at different experiences levels, here’s what I’d suggest:

NO TRAINING EXPERIENCE:

Based on the research we have, we know that training volume recommendations tend to be in a bell curve. I’d say at minimum for the brand new individual, we need at least 5 sets per muscle group per week and at the top end of the bell curve for a beginner would be 10 sets per muscle group per week. In my experience, most can recover just fine from either and therefore I like to set all muscle groups at 5 (minimum effective dose), while selecting 1-2 muscle groups to place at 10 (muscle groups selected will be based on their goals/preferences). And because we have no prior data on how many sets per week they were doing prior to working with us, this is a safe way to dive right in without overdoing it.

MINIMAL TRAINING EXPERIENCE:

This would be, say, 2 years or less. Still a beginner in the gym, without a doubt… However, these individuals do have enough experience to safely execute the compound lifts and can recover from a decent amount more than the brand new lifter. For these individuals, we take the same approach but start at the bottom of the normal volume bell curve (i.e. bell curve of 10-20 sets per muscle group per week). Then we select 1-2 specialization muscle groups to target with slightly more volume. This means 75% or more of muscles are set to 10 sets per muscle per week, while 1-2 are set at 15 sets per muscle per week. Once again, since we assessed their current volume prior this is likely going to be a safe route to take because either a.) we saw that they were just not doing enough, b.) they were doing this amount already but it wasn’t properly programmed, or c.) they were doing too much and they actually needed more guidance on how to get MORE out of LESS.

MODERATE TRAINING EXPERIENCE:

Now we move into an intermediate training program and as you can probably guess, we take the same approach but we up the volume just slightly. We start with a baseline of 15 sets per muscle group per week and unlike the other categories, we wait a full mesocycle, if not two, before specializing on anything. I like to see that the individual can still fully recover from 15 sets across all body parts before moving 1-2 muscle groups into the 17-20 sets per muscle group per week range.

ADVANCED TRAINING EXPERIENCE:

Lastly we have the individual who has a decade or more of training experience and not only CAN handle a lot of volume, but NEEDS a lot and is already doing a lot prior to working with you (based on your assessment of their prior training program design). For this individual we program every muscle group at 20 sets per muscle group per week and before increasing anything above that, we select 1-2 muscle groups that DO NOT need as much volume (based on genetics or biased development) and lower the volume there to replace with more volume elsewhere (that needs more development). We do this to still manage global and neurological fatigue (which is more about TOTAL volume). If able and needed, we will then increase by 1-2 sets per week per muscle until we reach their maximum recoverable volume.

What About Smaller, Secondary, Muscle Groups?

This is where things can get a little more specific and “in the weeds” because the total fatigue generated from a bench press is clearly different than the fatigue from a cable chest fly, since the total load is different, total amount of muscles involved in the exercise is different, and the amount of energy put into the exercise itself, both physically and psychologically, is different. Therefore a fly is far less fatiguing than a bench press, obviously.

So what you can, and should, do is cut these numbers (of total sets) in half for smaller muscles like rear delts, biceps, triceps, abs, etc… This means that direct bicep training, for example, can be more like 6-8 total sets per week since they’re also going to be getting 10 to 20 partially-stimulative-sets from every row and pulldown you do in your training as well. And although it’s not a direct stimulus, it’s still an indirect stimulus to the muscle and that does count towards overall stress and recovery to the muscle, tendon, ligament, joint, and nervous system. The same applies to triceps, due to all the pressing when working chest and shoulders, as well as glutes from the indirect stress they get when squatting for quads or performing stiff leg deadlifts for hamstrings.

If we were to create an actual formula for counting everything and programming properly, we would want to either count half and full sets for everything we do (bench press = 1 for chest, 0.5 for triceps and front delts) or count ONLY direct sets (bench press = 1 for chest) and simply program less total sets per week for anything that is a secondary muscle group or would be counted as a half-set when counted the prior way.

Determining Recovery Demands

Something to add into this discussion is the simple fact that certain exercises will have a bigger “cost” when it comes to recovery. Meaning that some exercises are more neurologically fatiguing or harder on the joints, for example. We can also take this a step further and individualize the stimulus-magnitude, which will increase or decrease each specific individuals recovery demand for a given exercise. By this I mean that some exercises just simply work better for certain people compared to others! And if I personally feel a maximal stimulus in a given exercise and you do not, then that exercise may be better for me BUT ALSO require more recovery, since I’m getting more out of it.

Now, how do we figure this out? Easy, run through a sequence of questions inside your training as seen in the video below:

In the video I go over how to determine the best exercises for you specifically, but while doing so I lay out a framework to determine what will give you the best mind muscle connection, lowest injury risk, lowest fatigue, highest stimulus, and more… and by the end of it, you’ll also know how to maximize your recovery within these volume landmarks.

Training Volume Practical Recommendations:

Alright, to wrap things up — here are my 5 recommendations and takeaways to apply into your training, asap:

- Assess your current volume by tracking your total sets per muscle group per week.

- After having a baseline number for each muscle group, begin to increase your volume by 10-20% per week (assuming you’re stalled out and ready to gain more muscle).

- When a plateau arises, continue to increase volume by 1-5 sets per muscle group per week (ONLY after all other attempts to break plateaus have been executed).

- Once you’ve reached the 20 sets per muscle group per week range, you likely do not need more volume — but rather need to periodize exercise selection, progression models, and/or intensity, or simply work harder (effort) in the gym, in order to break through plateaus.

- Rarely ever will you need to move all muscles to or beyond the 20+ sets per muscle group range, however at times it can be beneficial to cycle volume — this would allow you to accumulate more volume as the weeks progress, peaking at a high end (20-25) and then deloading before returning to the beginning of the cycle.