Research Review #10

Brandon Roberts, Ph.D., CSCS*D

Chief Science Officer

*Note from Brandon: if you want to learn how to interpret research go read each study before reading the breakdown below, take notes, then compare your interpretation to mine.

Study Title: Effects of resistance training performed to repetition failure or non-failure on muscular strength and hypertrophy: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Question: Is training to failure necessary to optimize strength and hypertrophy?

Why

A few months ago we covered training to failure or non-failure (blog/podcast). The study found that training to both muscle failure and non-failure were similarly effective at inducing muscle hypertrophy, muscle strength gains and changes in muscle architecture in trained individuals. The study findings weren’t groundbreaking, instead they added another data point to a growing body of literature on the topic. Consider it an eternal quest to determine how to get the best gains.

Oftentimes, the best way to answer a question is with a meta-analysis. This reduces each experiment to a single data point or a few, depending on the outcome. However, as we saw in the last blog on cold vs heat therapy for DOMS, there can be huge differences in the type of studies that go into a meta-analysis. This muddies the water and makes it difficult to determine the results. Therefore, the more similar the studies the better.

The current review is actually not the most up-to-date meta-analysis on training to failure vs non-failure. This one was published in early 2021. There was a more recent meta-analysis on the same topic also published, but we’re going to look at how they compare so that you can better understand the differences. In science, a few months can mean one or two relevant studies being published and since your study is with reviewers or editors you may not be able to include the findings.

Who

Studies with healthy subjects that had a minimum duration of six weeks were considered for inclusion. Importantly, studies that used blood flow restriction resistance training or concurrent training were not included.

Study participants were young and healthy with some having experience in the gym (trained) while others had none (untrained).

Study Details

15 studies were identified that met the authors inclusion criteria for muscle strength. All participants in the studies were young adults with a median age of 25. There were six studies on trained participants (40%) and nine on untrained participants (60%). The studies ranged from 6 to 14 weeks with a frequency of 2-3 days per week of training. Strength was mostly measured by 1RM though some measured it with isokinetic or isometric movements and one with a 6RM and another with a 10RM.

7 studies were identified that met the authors inclusion criteria for muscle hypertrophy. The demographics of the participants were very similar to the studies found for muscle strength. Two studies had trained participants, while five did not. Training programs were also similar to the strength studies. Muscle hypertrophy was measured via DXA, ultrasound, or muscle fiber cross sectional area.

The authors used a random effects meta-analysis that pooled results of all included studies to quantify the effects of failure training on muscular adaptations. They also performed a subgroup analysis of training status, body-region, exercise selection and training volume to determine their potential influence on results. These subgroup analysis help us understand if the findings apply to or are a consequence of specific factors within the analyzed studies.

Results

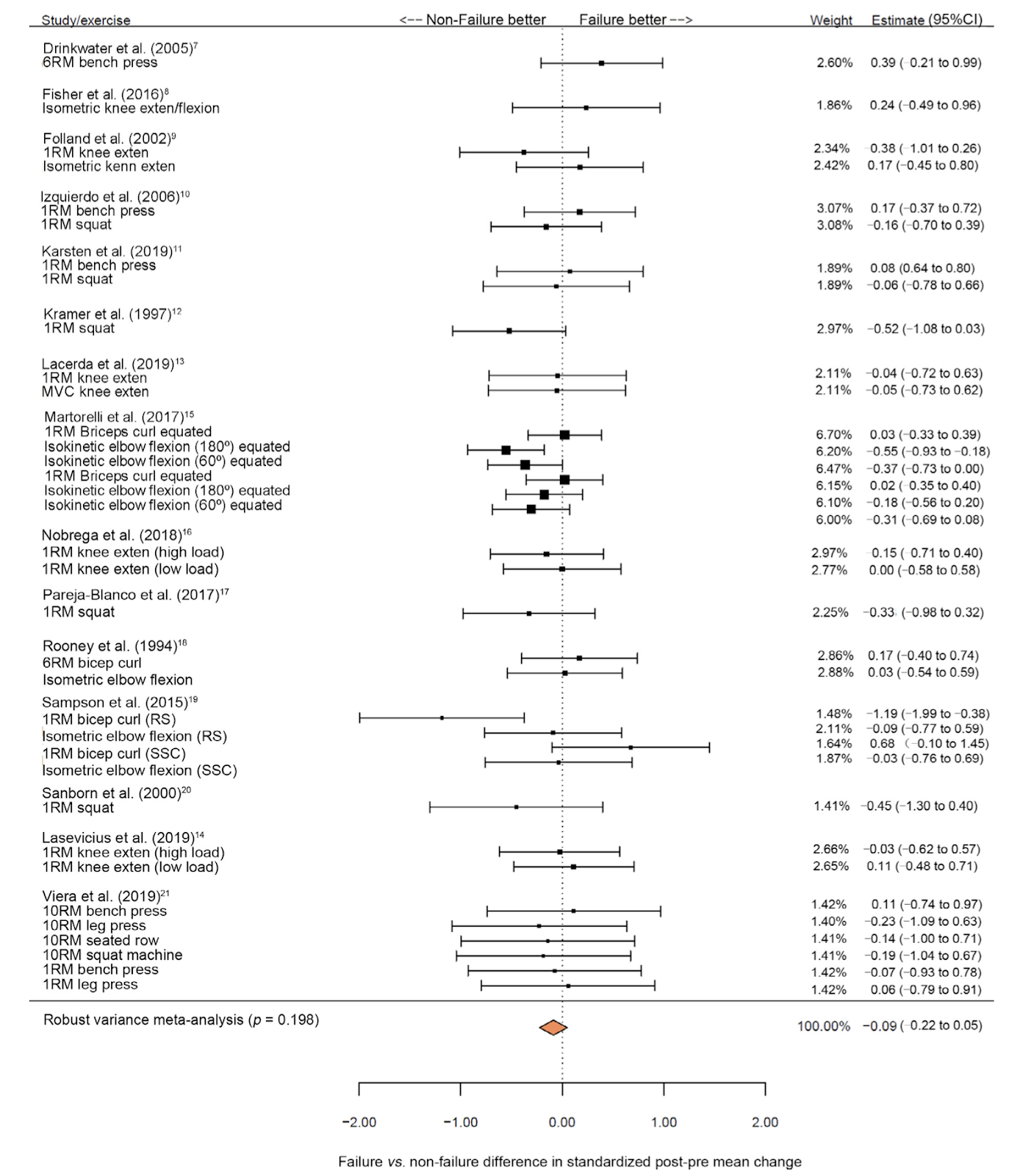

The meta-analysis for muscular strength gains indicated no significant difference between training to failure and non-failure (p = 0.198; ES = 0.09; 95%CI: 0.22 to 0.05). Subgroup analysis for studies that did not equate training volume showed a moderate and significant effect favoring non-failure training on strength gains (p = 0.025; ES = 0.32; 95%CI: 0.57 to 0.07).

Figure 1. The forest plot from the meta-analysis on the effects of training to failure vs non-failure on muscle strength.

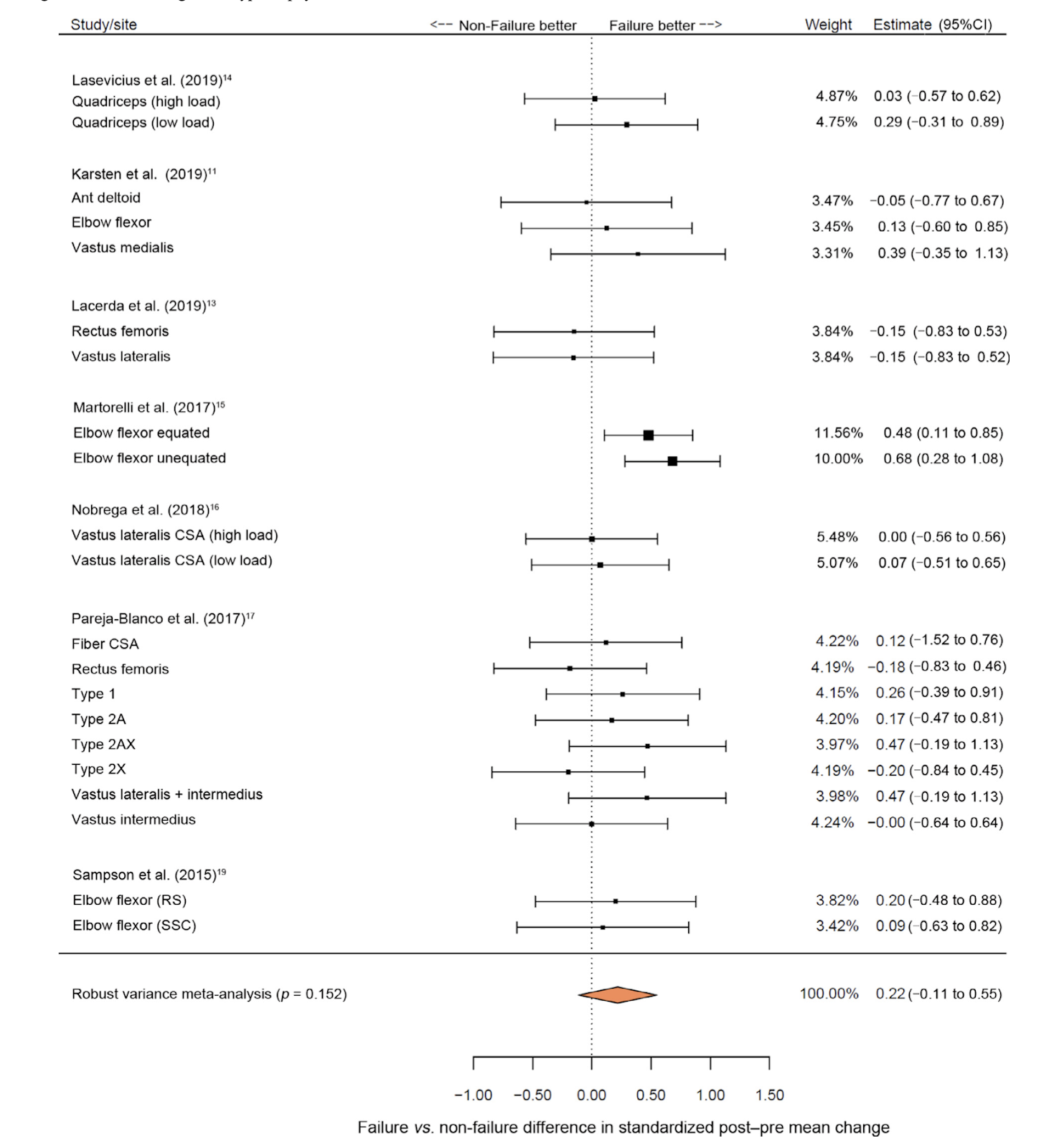

The meta-analysis for muscle hypertrophy indicated no significant difference between training to failure vs non-failure (p = 0.152; ES = 0.22; 95%CI: 0.11 to 0.55). Importantly, the subgroup analysis for resistance-trained individuals showed that training to failure had a significant effect on muscle hypertrophy.

Figure 2. The forest plot from the meta-analysis on the effects of training to failure vs non-failure on muscle hypertrophy.

Author’s Answer

“While this meta-analysis showed no significant differences between the effects of training to muscle failure or non-failure on muscle strength and hypertrophy, these results are specific to the population analyzed in all included studies—young adults. Therefore, future work is needed to explore the effects of training to failure vs. non-failure among middle-aged and older adults. Additionally, our results are specific to studies that used isolated traditional resistance training programs.”

“Training to muscle failure does not seem to be required for gains in strength and muscle size. However, training in this manner does not seem to have detrimental effects on these adaptations, either.”

Dr. Schoenfeld, one of the authors on the paper, offers his take here.

My Answer

While the authors did not find differences in strength or hypertrophy outcomes when comparing failure vs non-failure in the overall analysis, there was an effect in trained participants for hypertrophy. This makes sense because training to failure is a skill. Think about the first time you stepped into the gym. You may have stopped training way before actual failure because of pain, discomfort, or not wanting to hurt yourself. That’s smart. It’s also why trained people (like most that are reading this) adapt well ⸺ because they learn how to push themselves appropriately. That’s not the only reason though. We know that to grow we need to progressively overload our muscles, forcing them to adapt. It’s much easier to track that type of data (reps/set/load) if we just need to go to failure. If we introduce something like RPE into the mix there becomes more room for error. In fact, no studies in this analysis used RPE at all, they all used percentages of 1RM or repetition maxes for training purposes.

As previously mentioned, there was another meta-analysis recently published on training to failure vs non-failure. The authors found that training performed to failure resulted in an increase in muscle size compared with non-failure. They also completed a subgroup analysis on volume (equalized or not equalized) finding an advantage in favor of the failure group when considering non-equalized training volumes. On the contrary, no significant difference was found between failure and non-failure when volume was equal. This directly goes against the findings of the study we’re reviewing, but not if you think about it closely. If two groups do the same workout, and one goes to failure, they’re probably doing more volume which would result in more hypertrophy in a short-term study. However, if you extrapolate that type of training over time it may have problems.

The main difference between the two publications was the studies in the actual meta-analysis. This is why it’s important to look at them closely. For example, the Vieira et al., study included a larger age range with 13.5% of the participants being ~65 years old. As you can imagine, that plays a role in adaptations because older adults have anabolic resistance, which describes the reduced stimulation of muscle protein synthesis to a given dose of protein/amino acids and contributes to declines in skeletal muscle mass, which could lower the effect on muscle growth.

Another difference is strength outcomes. For example, Grgic et al., included isometric strength, meaning studies like this one were in the analysis, while Vieira et al., did not. Grgic et al., also included data on 10RMs which are a far cry from a true strength measure. That appeared not to matter too much since they both found no differences in strength between failure and non-failure training. A previous meta-analysis from 2016 was done on eight studies comparing the effects of failure vs non-failure on muscle strength. The data indicated that there were no significant differences between the failure and non-failure training for strength. This data matches both meta-analysis. Therefore, we have ample evidence (for now) that training to failure does not benefit overall strength. In fact, one may argue that it is slightly detrimental given the tendency for the analyses favoring non-failure.

How can we apply this?

This part hasn’t changed from the last time I wrote about failure. There still doesn’t appear to be an overall benefit of training to failure compared to non-failure for strength and likely not for hypertrophy either. Practically, we should train shy of failure most of the time and be in a good physiological place when training to failure. Since these studies are short (6-14 weeks) we still don’t know if failure has a major long-term benefit or detriment.

What’s next?

Scientists need to continue to manipulate variables to find out where training to failure is or isn’t beneficial. There are a hundred different combinations, so it might be a while.