Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) vs. Percentage Based Training (PBT)

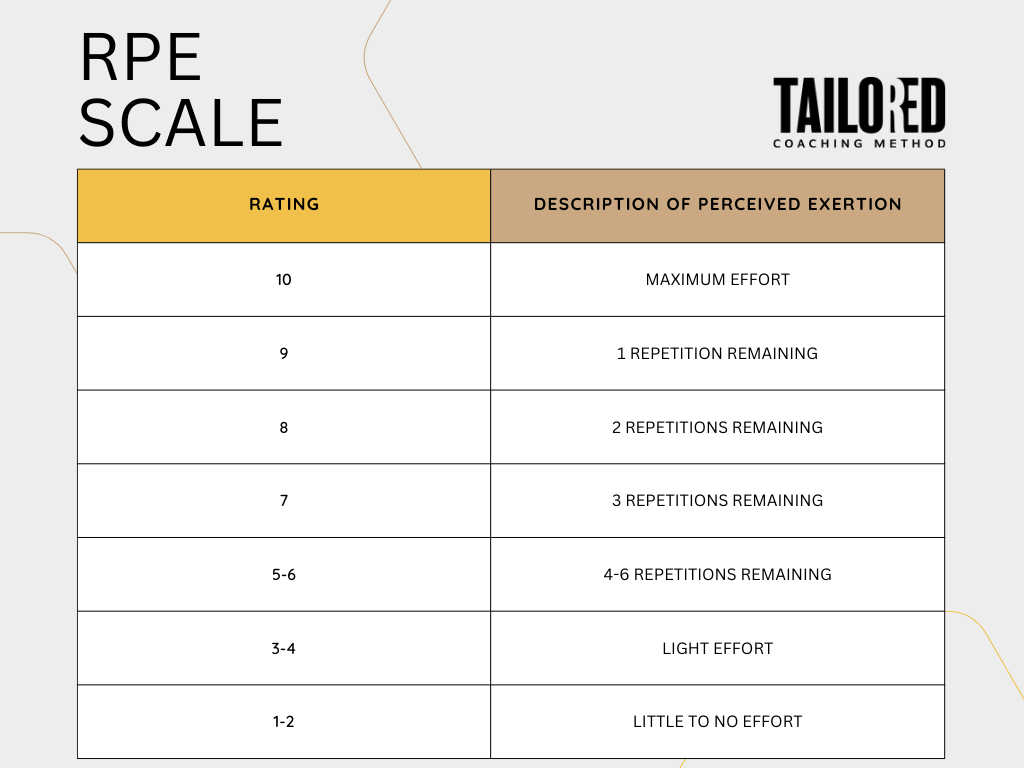

Training intensity is more than a number — it’s how you get results in the gym. One of the first measurements of training intensity was rating of perceived exertion (RPE), developed by Dr. Borg in the 1970s. The initial RPE scale was from 6-20, and later a scale was developed that measured intensity from 1-10. Much later, the repetitions in reserve (RIR) method of RPE was developed and has been studied by several coaches and scientists (Mike Tuchscherer, Dr. Helms, Dr. Zourdos, Dr. Hackett) and has become a prominent method to measure intensity for people who strength train. These two methods are subjective, meaning they are based on a person’s perception of intensity which can be influenced by numerous factors, such as sleep, stress, fatigue, nutrition, and soreness.

On the other hand, percentage based training (PBT) has been around for a very long time and it’s somewhat unclear who created it, but a lot of research on the topic has been completed by Dr. Stone and Dr. Kraemer. PBT involves doing a 1 rep max test (or estimating 1RM) then basing your training on a percentage of 1RM for your program. 1RMs are usually completed at the end of each training block (4-12 weeks) to adjust for the next block so that you can keep adapting to your workouts.

In this blog we’ll cover several studies characterizing or comparing RPE/RIR and PBT. Then, we’ll help you apply it to your training programs. We’ll compare PBT and RPE/RIR through the lens of the RPE/RIR to make the science more digestible. The goal is to help you understand when to use each option, and when it might not matter that much — in an evidence-based way.

What Does Research Say About RPE and RIR Scales?

The first study on the RPE/RIR scale was published by Zourdos et al in 2016. The primary aim was to compare RPE/RIR at different intensities of 1RM squat in experienced (those who had >1 year experience performing the barbell back squat) and novice (those who had <1 year experience) athletes. There was a strong inverse correlation (r = -0.88) between average rep velocity and RPE/RIR. They also found that RPE aligned with 1RM most of the experienced group giving an RPE of >9.5 at their 1RM. This data indicates that RPE/RIR is a good measure of intensity and the harder the rep, the higher the RPE.

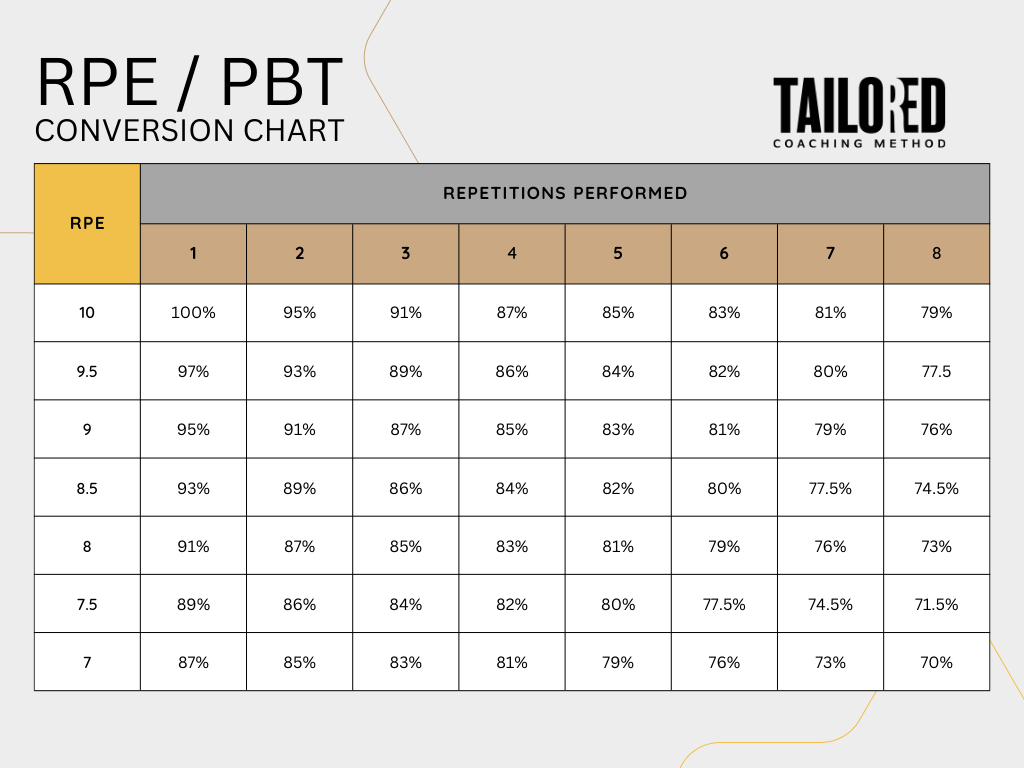

Shortly afterward, Helms et al., (2016) wrote a manuscript on the application of RPE/RIR for resistance training, republishing the below tables from the original Zourdos study (Table 1 & Table 2).

RPE/RIR faced an obstacle shortly after it was created. A massive study (n = 140) examined the ability of people to predict the number of repetitions they could perform to muscular failure, with a given load, across a number of exercises and range of experience levels. Overall, the data suggested people underpredicted the number of repetitions they could perform to failure, but the average difference was reduced with greater experience lifting. The data further indicated that participants were not perfectly accurate at predicting repetitions to failure with error rates ranging from 2.64 to 3.38 repetitions.

Considering the predominant training goal reported by the participants in this study (muscular hypertrophy), a less than perfectly accurate ability to predict repetitions to failure may interfere with maximizing muscle growth. The caveat with this study was that the participants only did a single set to failure and they weren’t familiar with the RPE system.

A follow-up study was completed by Helms et al., (2017) to better understand the ability to select loads using the RPE/RIR scale for a single set of squat, bench press, and deadlift. The study found that powerlifters can accurately select loads to reach a prescribed RPE/RIR. However, accuracy for 8-repetition sets at 8 RPE/RIR may be better for bench press compared with the squat, and accurately rating squat power-type training RPE/RIR may take 3 weeks to reach peak accuracy. Finally, bench press RPE accuracy seems better closer to failure.

A more recent study by Zourdos et al., found that being farther from failure and having high rep sets are associated with more inaccurate predictions of RPE/RIR and another study by Ormsbee et al., (2019) found that the RPE/RIR is effective to gauge resistance training intensity in college age men. Ultimately, the research indicates RPE/RIR can be a good tool if you have a few years of training experience and learn the RPE/RIR measurement system.

Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) vs. Percentage Based Training (PBT)

The research comparing RPE/RIR vs PBT is fairly small. The first study compared two resistance training protocols with matched repetitions, sets, exercises, and rest periods, but with differing methods of load prescription; one group using percentage of pre-test 1RM and the other using the RPE/RIR scale. The authors found that there were no statistical differences between the two groups, indicating the two training programs performed similarly. However, there were several points in the study where average RPE per set, relative volume and relative intensity per repetition were higher in RPE/RIR vs. PBT group. This means that the RPE/RIR group was training harder, which may result in better gains over the long-term.

The next study had 31 resistance-trained men complete twice weekly RPE/RIR or PBT for front squat and back squat. The results indicated that both the RPE/RIR and PBT groups increased squat strength in a 12-week training program; however, the RPE/RIR group increased more than the PBT group. Interestingly, the RPE/RIR trained at a higher intensity, which allowed the subjects to increase the load lifted and total volume, which likely explains the benefit over PBT.

There are a few meta-analyses on the topic that can help us determine how RPE/RIR compares to PBT. One meta-analysis suggests that an auto-regulation method, like RPE/RIR could be more effective than the fixed-loading method in maximum strength training. However, another meta-analysis suggests that autoregulated and standardized load prescriptions produce similar improvements in strength. Until more research is published it’s unclear which is the best option for strength.

How To Use The RPE or RIR Scale Properly

In this section, we’ll cover how and why you may want to apply the science above to your training.

One reason we might want to not use PBT is so that we don’t actually have to do 1RM testing. Most people don’t need to do 1RMs (including athletes) and they can increase the risk of injury. In addition, it’s hard to do 1RM testing on accessory lifts (e.g., bicep curls, tricep pushdowns, etc.,). Our previous blog on 1RM estimates can help if you really need to do PBT, but RPE/RIR is an alternate method that can be useful for those not wanting to do a 1RM.

There are also day-to-day fluctuations in how we’re feeling, so autoregulation methods like RPE/RIR give us a method to adjust training quickly. Methods of determining intensity such as percentage of 1RM based on a previous performance may not be representative of a person’s current status. Furthermore, 1RM is not stable in people new to training, and it can be suppressed by fatigue from previous training in those who are experienced. Thus, if a 1RM or RM test happens to be reflective of an abnormal performance, positive or negative, subsequent training loads could be lighter or heavier than intended. Likewise, even if a test does accurately reflect current strength, subsequent percentage 1RM loading does not account for day-to-day fluctuations in performance.

Finally, studies have shown interindividual variation in the number of repetitions performed to momentary failure at fixed %1RM so people may not be using the optimal number of reps based on their %1RM.

Using RPE/RIR allows you to autoregulate the load based on how you are feeling that day. If you feel good (aka strong) then you can increase the load to match the prescribed RPE/RIR. If you’re having an off day, you can also decrease the load to match the prescribed RPE/RIR. Comparatively, with PBT, some people may not complete their programmed training while others may be able to do more than what was programmed for that day.

It’s best to use the RPE/RIR method after you’ve been training for a while and have been familiarized with the scale. Estimating your RPE/RIR is a skill that takes time to develop. At first, you may undershoot and overshoot your prescribed RPE/RIR. One way to check yourself is occasionally take a movement to failure to see how many reps you actually had left in the tank. Ultimately, the more you use RPE/RIR, the better you will become at it. To make RPE/RIR more useful we can use ranges (e.g., RIR = 8-9) and use historical training data (aka experience) to determine what weight range to pick. By basing loads off prior training and with three conditions (exercise, rep #, and RIR range) you can establish very accurate training targets for each RIR range.

Gauging RPE/RIR for low intensity high-velocity power training is difficult because of the inability to determine how far from failure a person might be. However, using an intensity cap of RPE 4-5 could be implemented for low intensity high-velocity power training to ensure movement speed remains appropriately high. Put differently, if the lifter can accurately estimate RPE/RIR, the load is likely inappropriately heavy for this type of training and should be reduced to maintain velocity.

For training focused on strength alone, it may be best to use PBT for a few key movements like squat, bench press, and/or deadlift. As displayed in Table 2, 87% of 1RM is roughly equal to 4RM, therefore 4 repetitions with 0 RIR, 3 repetitions with 1 RIR, 2 repetitions with 2 RIR, or 1 repetitions with 3 RIR would all be roughly equivalent in load and representative of the lower end of the intensity threshold for maximal strength development.

In addition, it seems that RPE/RIR ratings are more accurate when performing low repetition sets closer to failure. For hypertrophy training, RPE/RIR seems to be the best fit because you want to train close to, but not necessarily at, failure. The RPE/RIR system allows you to adjust within your workout.

Sample Upper/Lower Workout Using RPE/RIR:

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 |

| Back squat: 4×8-10, RPE 8 | Bench Press: 3×8-10, RPE 9 | Deadlift: 3×6-8

RPE 9 |

Bench Press: 4×12,

RPE 9 |

| Leg Press: 4×10-12, RPE 8 | Cable fly: 4×15-20,

RPE 8 |

Front Squat: 4×8-10, RPE 8 | Incline BP: 4×8-10,

RPE 9 |

| Leg extension: 4×10-12, RPE 8 | Lat pulldown: 4×12-15, RPE 8 | Hip Thrusts: 4×12,

RPE 9 |

Pull-ups: 4×8-10,

RPE 9 |

| Leg curl: 4×10-12,

RPE 8 |

Seated Row: 4×12-15, RPE 8 | Lunges: 4×12-15,

RPE 9 |

Standing Row: 4×8-10,

RPE 9 |

| Calf raise: 4×10-12, RPE 8 | Tricep: 4×12-15,

RPE 9 |

Calf raise: 4×15-20, RPE 9 | Triceps: 4×15-20,

RPE 9 |

| Cable pull-through: 4×15-20, RPE 8 | Biceps: 4×12-15,

RPE 9 |

Biceps: 4×15,

RPE 9 |

References

- Zourdos MC, Klemp A, Dolan C, et al. Novel resistance training-specific rating of perceived exertion scale measuring repetitions in reserve. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(1):267-275.

- Helms ER, Cronin J, Storey A, Zourdos MC. Application of the repetitions in reserve-based rating of perceived exertion scale for resistance training. Strength Cond J. 2016;38(4):42-49.

- Steele J, Endres A, Fisher J, Gentil P, Giessing J. Ability to predict repetitions to momentary failure is not perfectly accurate, though improves with resistance training experience. PeerJ. 2017;5:e4105.

- Helms ER, Cross MR, Brown SR, Storey A, Cronin J, Zourdos MC. Rating of perceived exertion as a method of volume autoregulation within a periodized program. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2018;32(6):1627.

- Helms ER, Brown SR, Cross MR, Storey A, Cronin J, Zourdos MC. Self-rated accuracy of rating of perceived exertion-based load prescription in powerlifters. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2017;31(10):2938.

- Zourdos MC, Goldsmith JA, Helms ER, et al. Proximity to failure and total repetitions performed in a set influences accuracy of intraset repetitions in reserve-based rating of perceived exertion. J Strength Cond Res. 2021;35(Suppl 1):S158-S165.

- Helms ER, Byrnes RK, Cooke DM, et al. Rpe vs. Percentage 1rm loading in periodized programs matched for sets and repetitions. Front Physiol. 2018;9.

- Graham T, Cleather DJ. Autoregulation by “repetitions in reserve” leads to greater improvements in strength over a 12-week training program than fixed loading. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2021;35(9):2451.

- Zourdos MC, Goldsmith JA, Helms ER, et al. Proximity to failure and total repetitions performed in a set influences accuracy of intraset repetitions in reserve-based rating of perceived exertion. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2021;35:S158.

- Halperin I, Emanuel A. Rating of perceived effort: methodological concerns and future directions. Sports Med. 2020;50(4):679-687.

- Halperin I, Malleron T, Har-Nir I, et al. Accuracy in predicting repetitions to task failure in resistance exercise: a scoping review and exploratory meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2022;52(2):377-390

- Suchomel TJ, Nimphius S, Bellon CR, Hornsby WG, Stone MH. Training for muscular strength: methods for monitoring and adjusting training intensity. Sports Med. 2021;51(10):2051-2066.

- Zhang X, Li H, Bi S, Luo Y, Cao Y, Zhang G. Auto-regulation method vs. Fixed-loading method in maximum strength training for athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2021;12:651112.