*Note from Brandon: if you want to learn how to interpret research go read each study before reading the breakdown below, take notes, then compare your interpretation to mine.

[Rather listen to this Research Review? No problem, use the player below or tune in where-ever podcasts are available!]

Study #1

Title: Effect of resistance training to muscular failure vs non-failure on strength, hypertrophy and muscle architecture in trained individuals.

Question: Do we need to train to failure for muscle hypertrophy?

Why

A timeless fitness question is whether or not you should train to failure. The answer requires a little context, so we’re going to focus on muscle hypertrophy for this review. If you’re interested in strength, a recent meta-analysis found that training to failure does not result in an advantage compared to non-failure for muscular strength.

There are a number of important studies that help us understand if failure or non failure might be better for hypertrophy. One of those studies was done by Sampson et al. in 2015. The researchers had male participants train to failure or two reps short of failure for 12 weeks and found similar muscle growth in both groups. The concern with the Sampson study is that the participants were untrained and they only exercised biceps curls, which are a small muscle that might recover more quickly than something like the quads or lats. Another study by Nóbrega et al., in 2018, used untrained participants and employed the leg extension exercise to failure or non failure using high and low loads. They too found no differences in training to failure or not training to failure for hypertrophy. This adds another layer to the data indicating failure may not be necessary.

The current study adds to the literature by using trained participants. It also uses a novel method of progressive overload by increasing every participant’s training volume by 20% independent of what group they were in so everyone was getting a robust stimulus. Overall, the aim of this study was to compare the effects of resistance training to muscle failure (RT-F) and non-failure (RT-NF) on muscle mass, strength, and muscle activation in trained individuals.

Who

The study recruited 14 young (age = 23.1) healthy male participants with an average of 5 years of training experience. The participants were required to train their legs at least twice per week for the past two years with the leg press and leg extension exercises.

Study Details

A within-subjects design was used with one leg randomly assigned to failure (RT-F) and the other to non-failure (RT-NF). Failure was deemed as the inability to complete a repetition with the full range of motion.

Both groups trained with 75% of 1RM using the leg press and leg extension machines. Participants rested for two minutes between sets.

Based on individual training logs, each participant had their weekly number of sets increased by 20% to better explore individual adaptive responses on muscle hypertrophy.

Each leg was trained 2 days per week for 10 weeks.

Vastus lateralis muscle cross-sectional area (CSA), pennation angle (PA), fascicle length (FL) and 1RM were assessed at baseline and after 10 weeks.

Results

The failure group did about ~2 more reps than the non-failure group, which puts the non failure group at about 8RPE. That’s very realistic for programming purposes, since most hypertrophy work is programmed at 8-9RPE. If you need a refresher on RPE check out the January issue of our research review.

Volume load is the amount of load you lift (reps x sets x load) for an exercise. The two extra reps the failure group resulted in them completing ~11% more volume than the non failure group.

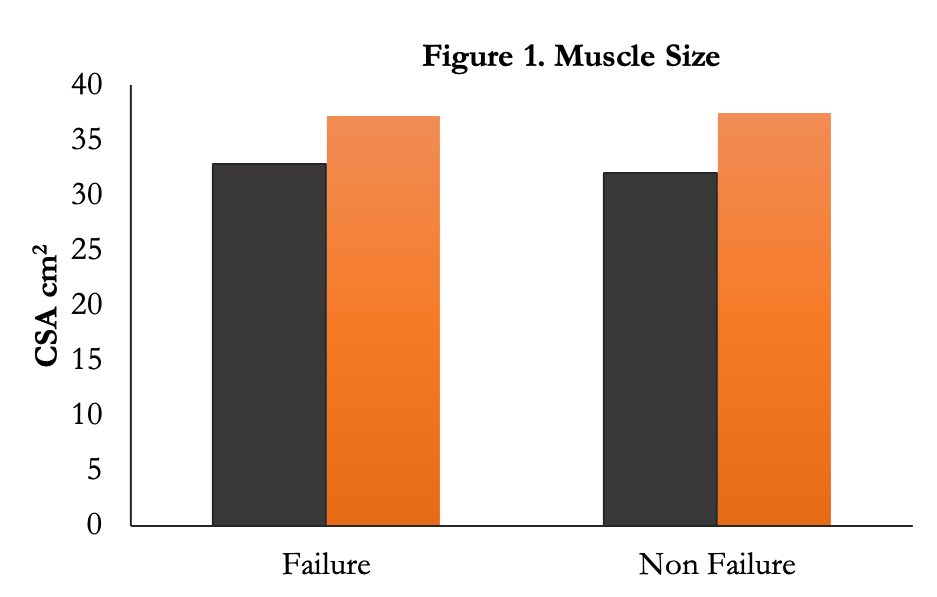

Now, the most important finding of this study was that muscle size was not significantly different between groups. Both groups improved over the 10 week training program [Figure 1]. When looking at percentage change, the non-failure group increased muscle size 5% more than the failure group, which equates to about 1.2 cm2.

Pennation angle is the angle between the longitudinal axis of the entire muscle and its fibers. When your muscle increases in size the pennation angle also increases and it is a very common physiological response to resistance training. For example, bodybuilders often have larger pennation angles than weightlifters because they have larger muscle bellies. Both training groups increased pennation angle yet there were no differences between groups, which is in line with the muscle size data.

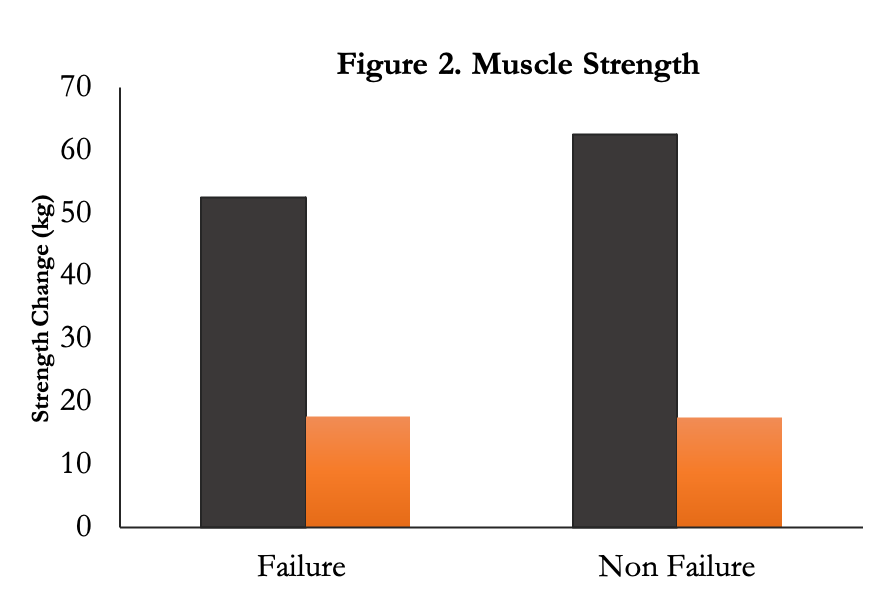

In terms of muscle strength, both groups increased 1RM leg press and leg extension. However, there were no significant differences between groups [Figure 2]. On an absolute level, there was a benefit (+10kg in 1RM leg press) for the non failure group.

Finally, no differences in muscle activation (EMG) were seen between groups.

Author’s Answer

“Our main findings show that both muscle failure (RT-F) and non- failure (RT-NF) protocols were similarly effective at inducing muscle hypertrophy, muscle strength gains and changes in muscle architecture in trained individuals. Additionally, both protocols produced similar EMG amplitude, confirming our initial hypothesis.”

My Answer

The underlying rationale for training to failure is to recruit high threshold motor units. Simply put, motor units connect nerves and muscles. If we train to failure we can recruit more muscle, which hypothetically could result in more stress on the muscle which creates impetus to grow. The issue with this theory is that we actually recruit all of our motor units a couple reps before failure. You can see this in the EMG data of the manuscript we’re reviewing – there were no significant differences in muscle activation between the failure and non failure group so there appears to be little rationale for training to failure since we’re already recruiting the motor units.

A problem with training to failure constantly is that it can increase the risk of overtraining and increase the risk of injury. Overtraining when resistance training is harder to accomplish than one might think, but when you pair it with endurance training (aka concurrent training) or sports training, it can occur more easily. The participants in this study were training legs twice per week, which is within the ideal range of frequency (1-3x). If we look at training volume the authors report that before the study the participants were doing about 19 sets per week for their quads. That could break down to something like 4-5 sets on leg press and leg extension, twice per week. Those numbers are fairly standard for bodybuilders but are a few sets higher than the general population. After increasing the sets by 20% the participants ended up doing 11.5 sets, on average, for the leg extension and leg press, respectively. The range was quite large with the participant doing the lowest completing 7 sets and the participant doing the highest at 42 sets (!!). Interestingly, the amount of hypertrophy wasn’t too variable between subjects if we look at the individual data points in the paper.

How can we apply this?

We can train short of failure consistently, and pick our spots when we want to train to failure. For example, maybe you save training to failure until the week before your deload or vacation. It probably won’t make much of a difference in the long-term but some people really like training to failure because they know they are pushing themselves.

What’s next?

If you guessed more research then you get a gold star. I think increasing participants volume by 20% ensured a robust stimulus so it may have diluted the group differences in muscle growth. The next step would be to repeat the experiment using different frequencies, muscle groups, and experience levels. If you only train a muscle once per week there’s probably some rationale to go to failure, but what if you train a muscle three times per week?

Study #2

Title: A large-scale experiment on New Year’s resolutions: Approach-oriented goals are more successful than avoidance-oriented goals

Question: What’s the best way to accomplish your goals?

Why

We’re a little over a month into the new year. How are your New Year’s resolutions doing? If you’ve been struggling, the results of this study may offer some help.

In 2019, roughly 40% of Americans made New Year’s resolutions. The most common goals were exercising, losing weight, and quitting smoking. The reason people choose the somewhat arbitrary date of January 1st is called the “fresh start effect”. This effect is due to a new mental accounting period, which condenses past problems to a previous period, causes people to take a big-picture view of their lives, and then re-evaluate what they’re doing and what they can improve in their lives.

Previous research has found that people who have a greater use of stimulus control, willpower, and a consistent use of self-reward achieve greater success rates with their resolutions. In another paper from the same group, the authors found that readiness to change was related to positive outcomes. This tells us that you need to be ready to change and have some willpower to help change occur.

The current study had three aims that can help us better understand resolutions:

- Determine what types of resolutions people make when they are free to formulate them.

- Determine whether or not different resolutions reach differing success rates.

- Examine whether or not it is possible to increase the likelihood of success by administering information and exercises on effective goal setting.

The authors hypothesis was that more supportive material and assessment points would result in greater success rates and that approach-oriented goals would be more effective than avoidance-oriented goals. If you’re thinking “duh” you may want to keep reading. The results are surprising.

Who

Participants were recruited from the general public and were invited to register for the study through social media (Facebook, Twitter, etc) during the last week of December 2016 . The average age was ~45, with 81% of the 1062 participants being female. Most participants were married (73%), had children (75%), and were employed (75%). This demographic essentially replicates the average person in the USA even though the study was based out of Sweden.

Study Details

Each participant was randomized to one of three groups. The website performed the randomization automatically after participants signed up online.

One group received no support on their resolutions, thus served as the control group. They had follow-ups at the end of January, June, and December.

Another group received some support. The was mainly information on a website about the positive effects of receiving social support when trying to accomplish a goal. The participants in this group chose a person responsible for supporting them throughout the year and were followed-up with by the researchers at the end of each month. The participants in this group were also sent information on how to cope with setbacks when trying to accomplish their goals.

The final group received extended support. The received the same as the “some support” group above plus information about the value of goal setting termed SMART – specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-based. These participants were asked to frame their goals as actively doing something instead of avoiding something. These participants were sent three more emails with information and exercises regarding motivation, thought patterns, and negative spirals in relation to New Year’s resolutions. They were also provided information about the value of interim goals and were instructed to formulate six such goals for their New Year’s resolutions

All participants were assessed for success on a ten-point scale from 0-100% with 0% being “I have fully and completely abandoned my New Year’s resolutions” (0%) to “I am sticking to my New Year’s resolutions fully and completely according to the plan (100%). The authors used 70% as the cutoff for successfully completing goals.

Results

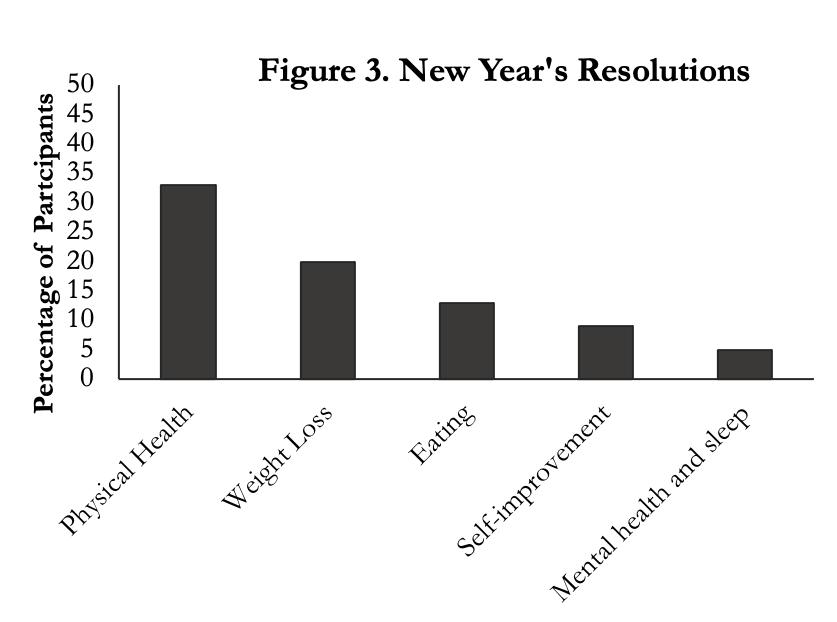

The most popular goal among the participants was improving physical health (33%). The second most popular category was losing weight (20%) and the third most popular category was the desire to change one’s eating habits (13%). The last two major categories were resolutions regarding personal growth (9%) and mental health/sleep (5%). The average number of resolutions was ~2 with 64% of participants making an approach-oriented goal.

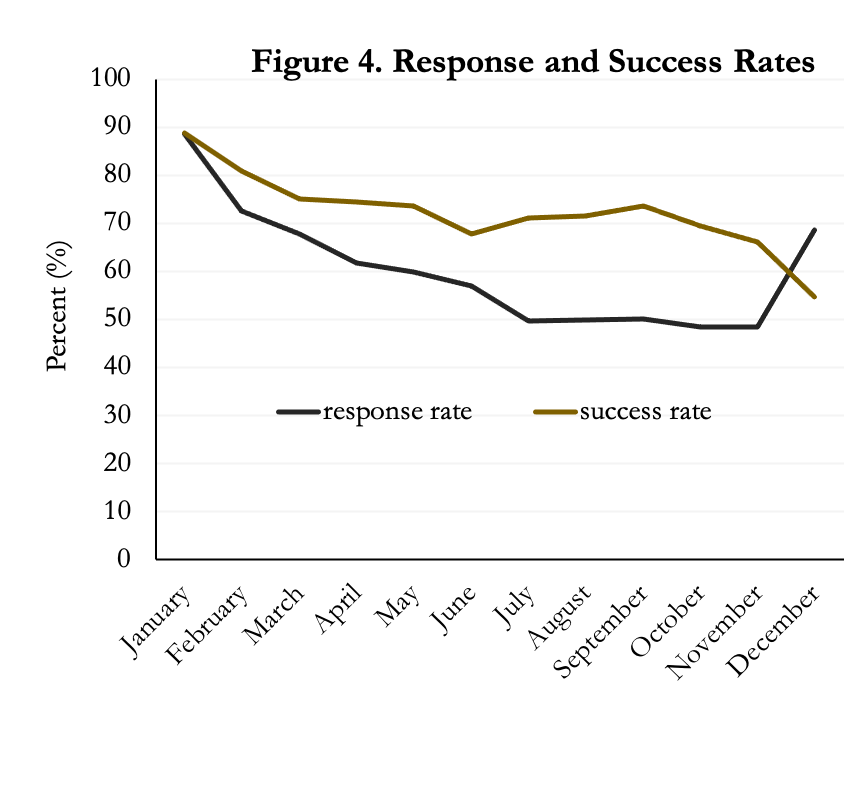

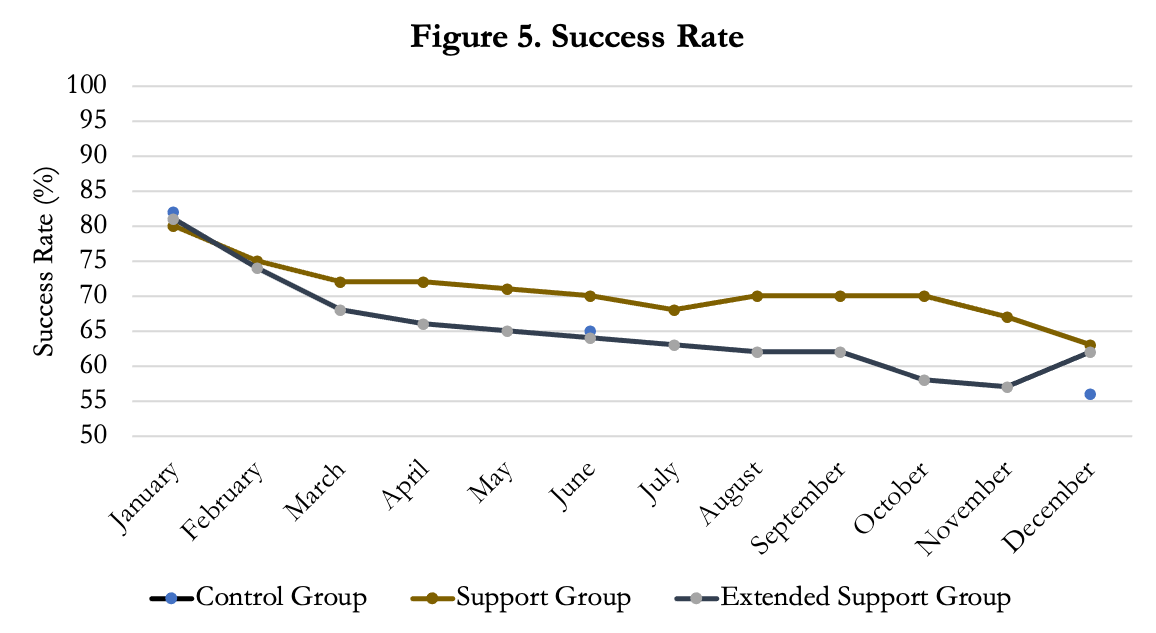

When doing survey research, especially when it’s virtual, the response rate can be very low and you generally lose participants over time. This happened in the current study, as you can see in the next graph. However, it’s important to point out that while both the response rate and success rate decreased over time, they were still above 50% for the whole year.

As expected, there was a significantly higher success rate for Group 2 (some support) versus Group 1 (no support. However, Group 2 was also more successful than Group 3 (extended support).

Among the participants who set approach-oriented New Year’s resolutions, ~60% considered themselves successful, compared to ~47% of participants who set avoidance-oriented resolutions.

Author’s Answer

“The results from this study suggest that New Year’s resolutions should be further studied as a potentially effective strategy for behavior change. Participants receiving some support reported greater success than those receiving extended support, and those receiving no support. This suggests that information, instructions and exercises regarding effective goal setting, administered via the Internet, could affect the likelihood of success—another question to further study.”

My Answer

The purpose of this experiment was to determine if different amounts of support can help people accomplish their New Year’s resolutions. We can extend the application beyond only resolutions to more broad goals that you start at any time. The authors found that some support and extended support was better than no support at all. That’s a reasonable finding. They also found that the group with some support outperformed the extended support group. The difference between the two support groups was only ~6%. This difference could be due to the way the extended group was told to create their goals. They were told to use the SMART method, which means they have a time component. If a participant didn’t complete their goal in the amount of time they proposed they would probably consider themselves not successful. To put that into context, if a participant lost 10lbs instead of 15lbs over the course of the first 6 months then they wouldn’t have accomplished their goal of “losing weight”. That’s pretty harsh.

There were also some similarities that likely accounted for the support groups success. They were provided information about the positive effects of social support and were all asked to involve another person in their resolutions. Participants in both groups were administered monthly follow-ups, and the first email sent to each participant included relevant information and exercises.

The authors also found that participants with approach-oriented goals were more successful than those who had avoidance-oriented goals. For example, an avoidance goal would be to stop getting a sugar laden treat from Starbucks while an approach goal would be to take coffee with you so that you aren’t tempted by Starbucks. They’re essentially the same goal but from different perspectives. You can use goals to your advantage with clients or yourself.

There was a fairly big limitation to this study. A self-signup process was used for recruitment. This is what we call a convenience sample so it was not random. This means that participants may be more motivated to rate themselves as successful in completing their goals OR more likely to make them in the first place.

How can we apply this?

You can use SMART and approach-oriented goals instead of avoidance goals. You may want to use an accountability partner to help you along the way. Finally, you want to make short-term and long-term goals that compliment each other (interim goals) so you can check on your progress as you go. A goal is a framework for taking an action. Are your goals taking you where you want to be? Do you need to focus on one goal instead of multiple goals?

What’s next?

This was one of the best studies on New Year’s resolutions. I think the next step is to use a method to rate people on their successful goal completion rather than have people rate themselves.