Each month I will cover two research articles on nutrition, training, sleep, supplements, or anything else that might help you. If you’d like me to cover a specific study next month send me a message on Instagram.

*Author’s note: if you want to learn how to interpret research go read each study before reading the breakdown below, take notes, then compare your interpretation to mine. I’ve now included a background section for those who only want to read my review and not the full paper.

Study #1

Big Question: Does alcohol hurt exercise performance?

Scientific Question: What are the effects of a HIIT program on physical fitness parameters in healthy young adults, and are they influenced by daily moderate beer or alcohol consumption?

Why

Most people like to have a beverage, maybe a brewski or a skinny marg. If you’re like me you’ve probably wondered whether or not that will stop your gains. Or at least if it’ll hurt them. In this study, we take a look at the exercise side of things to see if it will attenuate training adaptations. This study used HIIT, while past studies have used endurance or resistance training.

HIIT has been popular for a while now. There are all types, but some of the most common include repeated bouts of 30-45 seconds of intense exercise alternated with periods of active recovery or complete rest. It is quite effective too because it improves cardiovascular health and strength. Perhaps the most important aspect is that HIIT overcomes a common barriers people cite for not working out – the lack of time. Yet, it tends to be more difficult to recover from it compared to moderate or low-intensity exercise.

Who

83 participants met the inclusion criteria and, after the baseline measurements, the participants were allocated to a training (T) or a Non-Training (NT) group based on their preferences. Letting participants choose groups isn’t the best approach in science, but it does have some validity because we don’t randomize people to diet or exercise when we coach. They choose.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: average BMI, untrained, weight stable, and free of any health issues or injuries. What’s that mean? They were beginners. That’s ok. We need to keep that in mind when we interpret the results because people new to training respond extremely well, so the results may not apply to trained participants or athletes. Let’s keep an open mind for now.

Study Details

The study was a preregistered 10-week controlled trial. As you’ve seen me mention before in research reviews, pre-registration is a really good thing. It holds scientists accountable to the original experimental design and hypothesis. It also clearly defines what questions they’re asking.

So, what did the study do exactly?

First, they chose training (T) or not-training (NT). The training group completed 2 sessions per week starting at 40 minutes at RPE 8-9 and ramping up to 65 minutes per week at RPE 10 by phase 3. The RPE scale was 0-10 with 10 being maximal.

Before they started training participants chose whether they preferred receiving alcohol or alcohol-free beverages with meals. Males drank two beverages per day (lunch, dinner), while females drank one (dinner). The alcohol was given from Monday to Friday and there were no specific recommendations for Saturday or Sunday. If you were someone who volunteered to drink every day during the week – would you go drink on the weekends? Something else to keep in mind.

Those receiving alcohol were randomized between beer (5.4%) and mixed drinks (sparkling water with vodka, 5.4%). The non-alcohol groups consume alcohol-free beer or sparkling water. The beverage was ~22oz for men and ~11oz for women. The beer was Alhambra Especial and the alcohol-free beer was Cruzcampo. There might be a slight calorie difference we need to think about between those two.

The HIIT protocol consisted of a circuit of the plank, high knees up, TRX horizontal row, squat, deadlift, side plank, push up, and burpees twice per set with a passive rest between exercises and an active rest between sets (RPE = 6). The HIIT sessions were supervised by trainers in groups of ~8. Small group training, anyone? No weights needed here.

Attending at least 80% of sessions was required to be included in the final analysis. All training sessions were supervised by qualified and certified personal trainers. A gradual progression was used to ensure adherence to the protocol.

Results

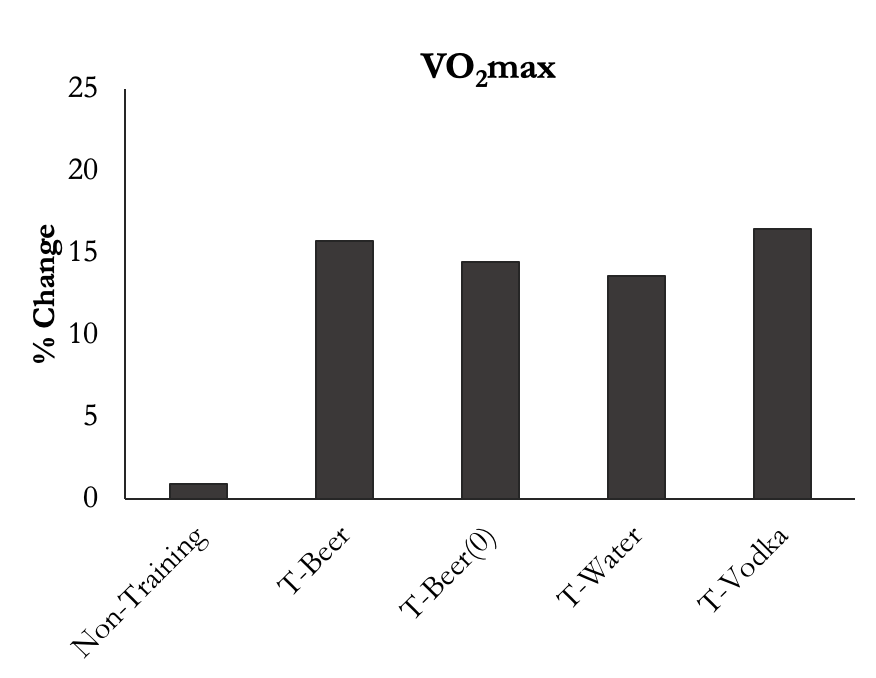

Let’s walk through the results by the outcome. First up was a VO2max test on a treadmill using the modified Balke protocol.

The second outcome was handgrip strength (kg) measured with a digital hand dynamometer. This measure isn’t great for strength in healthy young people, but it is important in aging research. However, these were young adults (18-19y) so a more practical strength test would have been good. No graph this time because it’s not super interesting. The authors only found a significant strength increase in the T-Beer(0) group although all training groups improved some.

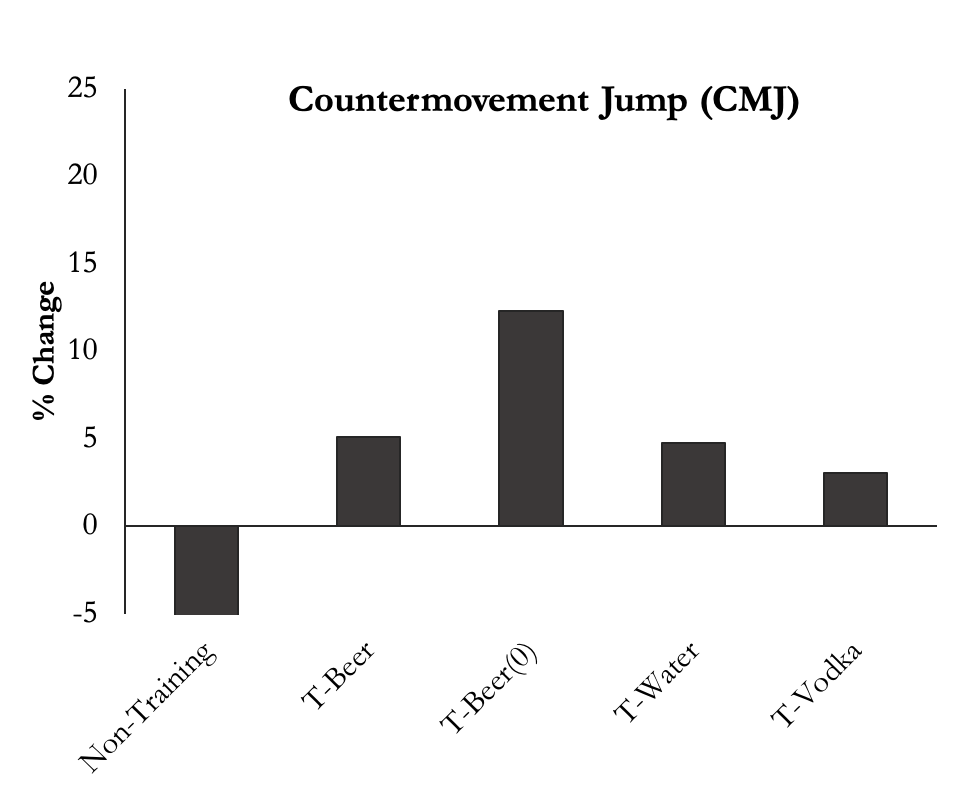

The authors measured a number of jumping outcomes like the Abalakov jump, drop jump, and countermovement jump (CMJ). The main difference between the jumps is that the Abalakov jump includes an arm swing and the CMJ has you put your hands on your hips. A significant interaction effect was found with CMJ, whereas no significance was observed in any other jump. I haven’t seen many scientists use the first two, so we’ll focus on the CMJ. The T-Beer(0) group significantly improved, while (sadly) the Non-Training group significantly lost jump height.

Author’s Answer

A 10-week structured and highly demanding exercise intervention improves cardiorespiratory fitness and handgrip strength in healthy adults. This was not influenced by the concurrent intake of beer in moderate amounts.

My Answer

As a reminder, one standard drink contains roughly 14 grams of pure alcohol, which is found in: 12 ounces of regular beer(5% alcohol), 5 ounces of wine, (12% alcohol), 1.5 ounces of liquor (40% alcohol).

The rationale for the amount of alcohol selected in this study was based on a “moderate amount” which is 2-3 drinks/day based on the author’s previous research. This study took place in Spain, which has a similar alcohol intake to the United States. I’m not sure that people who are serious about exercise and nutrition would consume 2-3 drinks per day but I would gamble that a lot of people drink at some point during the week. Probably on the weekend. Speaking of which, that’s my first issue with this study; the authors didn’t collect any data on weekend alcohol intake. However, there are two sides to this argument. All the groups improved by a good bit in 10 weeks with only 2 sessions per week so even if they did drink more or less during the weekend it didn’t have a huge effect.

HIIT vs moderate or lower intensity training is a common debate among fitness professionals. As you may have guessed, which method is best depends on the client you’re working with. There are some data indicating HIIT is better than continuous endurance training. However, I’m not a huge fan of HIIT for people who aren’t athletes. The exception is those who lack time to workout. HIIT is not easy to recover from and increases your risk of injury, especially if you don’t do it regularly. On the other hand, if you need to be powerful and explosive it’s worth including in your program.

Now, let’s look at a few studies on alcohol and exercise.

Two very old studies (Bond et al., 1983 & Houmard et al., 1987) found no effect of alcohol on endurance performance. More recent research indicates that acute alcohol consumption impairs muscular endurance, power, strength, and speed, as well as cardiovascular endurance. That shouldn’t surprise anyone. We aren’t looking at acute intake in this study though so what does the research say about drinking after exercise?

First off, alcohol consumption decreases skeletal muscle recovery and protein synthesis. That study used a ton of alcohol though (1.5g/kg) and I’m not sure people normally consume that much. Some simple math puts an average 65kg male at ~7 drinks in that study (1.5g/kg x 65kg / 14g EtOH per drink). That amount of alcohol also reduces glycogen resynthesis. So, maybe don’t drink 6-7 drinks after a workout.

Results from a previous publication by the authors with the same participants suggests that daily consumption of moderate amounts of beer or alcohol did not impair the gain of lean mass after a 10-week HIIT intervention. In fact, they found the positive effects of HIIT were not influenced by the regular intake of beer or alcohol at all. Again, not that surprising since these are untrained participants and it was only 1-2 drinks per day.

Let’s sidestep for a second and think about another factor that is indirectly affected by alcohol — sleep. Drinking alcohol before going to bed may help induce sleep with 2-3 drinks, but can disrupt restorative sleep cycles throughout the night, decreasing quality of sleep. This study didn’t report sleep even though they had it in their list of secondary outcomes.

From these studies we should see something somewhat obvious.

The dose makes the poison.

One more issue to cover before we finish. Statistics. The current study was powered on the “on a minimum predicted change of 15% in VO2max, handgrip strength and SJ jump between the intervention groups and the control Non-Training group” so it wasn’t designed to look at the differences of adding alcohol or not. That might be why we didn’t see any between-group differences. There probably were not enough people to detect a small difference between the groups. One other thing I have to point out is that the researchers didn’t do any sort of nutrition intake. Poor research methods 101.

In conclusion, a few drinks probably won’t hinder your overall performance in the short-term, but a lot of drinks can be detrimental. Couple this with the fact that there are no long-term studies (>12 weeks) on the effects of alcohol on performance or body composition in trained participants and we’re left scratching our heads. Did we learn anything new? Not really.

How can we apply this?

If you’re starting an exercise program it probably won’t make a difference if you drink moderately, so that’s important to tell to your clients. However, after you establish some good behavior changes (exercise, sleep, nutrition, etc) then it might be time to talk to them about alcohol intake. A few drinks on the weekend won’t hurt, but a few drinks per day probably does reduce long-term gains.

What’s next?

Most of the studies on alcohol and exercise are fairly extreme as you can see in my breakdown above. I think we need to do more practical research. For example, does drinking 3-4 beverages on the weekend, when you’re not training, make a difference? Is that different physiological or psychological? There are a ton of questions left to ask.

Study #2

Big Question: Is a 4 or6-hour feeding better for weight loss?

Scientific Question: What is the impact of 4h TRF versus 6h TRF on body weight and metabolic disease risk patterns compared to a control group?

Why?

Diets are hard. That’s part of the reason we have so many variations. Keto, carnivore, DASH, Atkins, and the list goes on. They all work and they all don’t work at the same time. Why? Adherence. For most people (and studies) diet adherence greatly decreases after 4-6 weeks. In studies this is reflected by high drop-out rates (~20-35%). It might be due to people’s frustration with constantly having to count calories or not being able to eat what they want. So, if we can make dieting easier by using restriction techniques then maybe it’ll be easier to lose weight for some people. I’d like to think scientists are looking for an answer not the answer.

Time-restricted feeding (TRF) has become very popular in the past few years. TRF is a form of intermittent fasting where food intake is restricted to a certain window during the day. There has been a lot of research in this area with the most popular ratio probably having a 16h fast and 8h feeding window. If we shorten the window even more we might be able to restrict calories because the meals will be larger, thus making us more fully in a small window.

Who?

58 middle-aged females with obesity were randomized into either the 4-h TRF group (n = 19), 6-h TRF group (n = 20), or the control group (n = 19). At the conclusion of the 10-week trial, there were 16 completers in the 4-h TRF group, 19 completers in the 6-h TRF group, and 14 completers in the control group. Notably, no one dropped out of the study due to dislike of the TRF intervention.

Wait. Let me run that back real quick. The authors say no one dropped out due to dislike of the diet, but there were 9 dropouts across all the groups due to scheduling conflicts. I’d bet those people who had a “scheduling conflict” also didn’t like the diet. However, that’s still only 15% of the people who started and fairly low for a diet study – most are in the 20-35% range.

Study Details

The study was preregistered and the authors used the STAR method of reporting. That’s what I call good science!

The study started with a two-week weight stabilization period with participants eating their normal diet. During the eight week trial, the 4h TRF group ate as much as they wanted from 3-7pm and fasted any time outside of that. The 6h TRF group ate from 1-7pm. There were no restrictions on the quantity or type of food the TRF groups could eat during the eating window.

During the trial participants met with the study coordinator to review their adherence log. It was the simplest adherence log ever because they only check that they ate during the correct times – not what they ate. There’s always the chance of misreporting, but when you limit feeding to short windows it’s probably less likely. People tend to respond well to diet rules. That’s part of why certain diets work so well. You make things black and white.

The primary outcome of the study was change in body weight, which was assessed every week. Body composition (fat mass, lean mass, visceral fat mass) was measured at baseline and at week 8 using dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA).

The authors measured blood pressure, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides. They also measured glucoregulatory factors such as Hba1C, fasting glucose, and HOMA-IR. There were even a few inflammation markers like TNF-alpha and IL-6.

One of the more practical things they measured was adverse events. The things people have issues with like headaches, gastrointestinal issues, and irritability.

Results

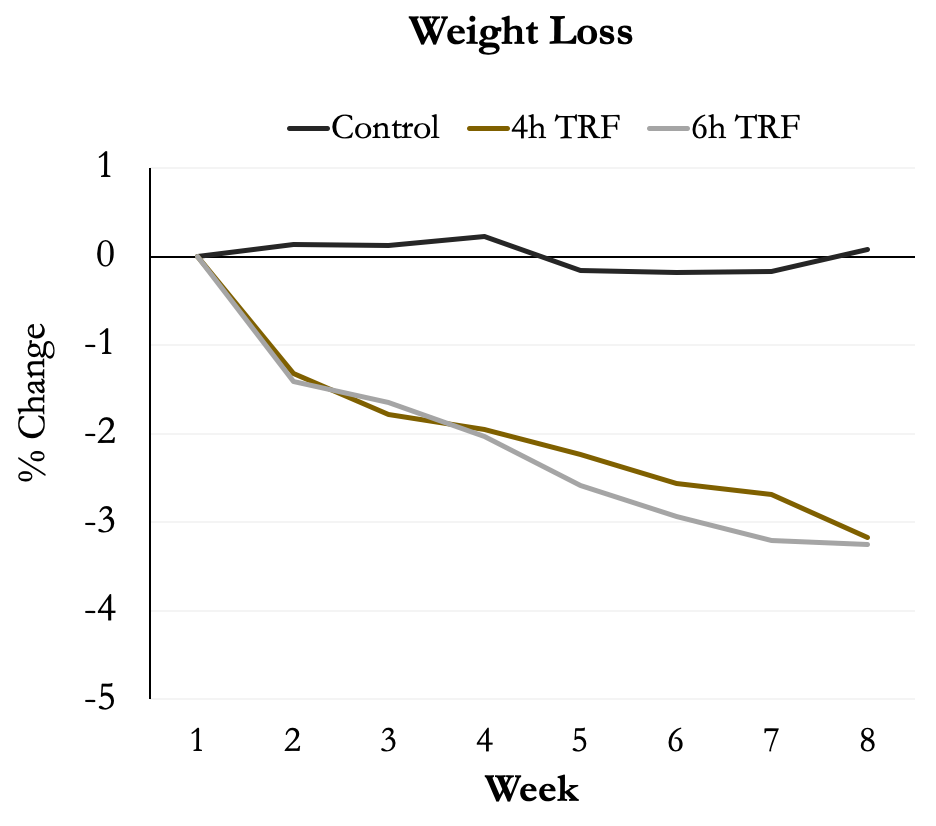

Participants lost a significant amount of body weight in both TRF groups by week 8. Yet, there were no differences between 4h and 6h TRF groups.

Adherence was tracked as mentioned above with participants compliant on ~6 days per week for the full diet. Reminder: there are seven days in a week. I wonder what happened on the last day? Refeed? I digress.

The authors noticed that they had a lot of variation in fasting time. This would indicate people didn’t use the full eating window they were given. However, the authors found these fasting extensions were not related to weight loss.

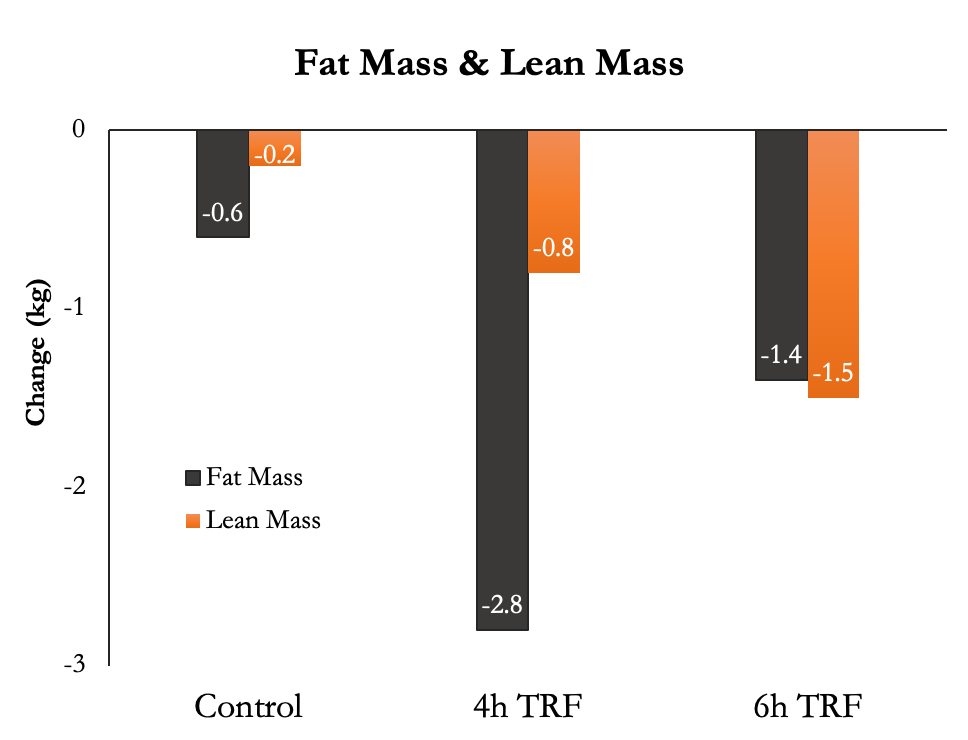

I’ve covered the importance between weight loss and fat mass in a previous research roundup, so let’s take a looksy here.

Both of the TRF groups lost a significant amount of fat mass with no difference between groups. No shock there. The more concerning finding is that the 6h group lost significantly more lean mass than the 4h group. We want to hold onto that while dieting. Granted, these participants weren’t training.

This study looked at a lot of health markers and given the study population it’s important to see if these improved. The authors found no differences in fasting glucose after the diet, but fasting insulin and insulin resistance were significantly reduced in the 4h and 6h TRF groups. There were no changes in HbA1C. These findings somewhat contradict each other.

Moving onto some other health markers, there were no changes in:

→ Blood pressure

→ HDL

→ LDL

→ Heart rate

→ Triglycerides

→ Inflammatory markers (IL-6 & TNF-alpha)

→ There was a significant decrease in 8-isoprostane for both TRF groups

Adverse events including dizziness, nausea, headaches, and gastrointestinal issues peaked during week 2 for both TRF groups but dissipated soon thereafter.

Author’s Answer

4h TRF does not produce superior weight loss versus 6h TRF. Both fasting regimens induce mild reductions in body weight over 8 weeks (~3%) and show promise as interventions for weight loss. Reductions in insulin resistance and oxidative stress were also noted, which bode well for the use of these regimens in preventing cardiometabolic disease. Compliance was similar for 4- and 6-h TRF, and both regimens reduced daily energy intake by ~550 kcal/day (30% reduction), without calorie counting.

My Answer

Spending a minimal amount of effort for the maximal amount of weight loss is every dieter’s goal. If you can use a specific diet to attain that you might be more inclined to try it. Recently, TRF has exploded in popularity both in research and in practice. One of the reasons is that people get to eat as much as they want. There’s a catch though. They can only do it for a certain amount of time. Realistically, most people don’t stuff their faces during their feeding window so what ends up happening is a natural reduction in calories because people are too full to eat as much as they normally would.

There are two studies that are somewhat comparable to the current study. The first is an 8h TRF study by Gabel et al., (2018) which had a very odd design. They used historical controls meaning that they just pulled data from an older study. Ultimately, the participants in the TRF group lost ~2.3% body weight. This study was a pilot study from the same group that published the current study we’re reviewing. I guess they decided to change their approach, which is what pilot studies are for.

Next, Gill and Panda, 2015 developed a smartphone app that instructed participants to use a 10h TRF diet for 16 weeks. They found a ~3.6% decrease in weight. This study was super neat considering a lot of people use apps to track calories. I may have to circle back to it in the future.

One more study for comparison’s sake. Wilkinson et al., (2020) found similar weight loss (3%) over 12 weeks in participants with metabolic syndrome who used a 10h TRF protocol. Those studies are proof of the concept that a number of different TRF windows can work.

Since those TRF studies didn’t use exercise, let’s cover some that did.

Tinsley et al., (2019) used a much more realistic approach for those who resistance train. They examined the effects of TRF, with or without β-hydroxy β-methylbutyrate (HMB) supplementation, with resistance training (RT). I’m not entirely sure why HMB was involved, but it didn’t make a difference in outcomes. The authors ultimately found that TRF did not impair lean mass gains or muscle hypertrophy compared to a normal (continuous) diet when energy and protein intake were similar. According to the study, they were eating ~1.6g/kg/day. Not bad at all, and well above what the general population would eat while dieting. On the weight loss side, the TRF group lost a significant amount of fat mass (2-4%). This study mainly tells us that we can use TRF without any training impairments.

An earlier study, by the same group (Tinsley et al., 2016), examined the effects of eight weeks of resistance training with and without TRF in order to assess nutrient intake and changes in body composition and muscular strength. The authors found that TRF reduced energy intake (-550kcal) and did not adversely affect lean mass retention or muscular improvements with training.

Last one for our exercise comparison. Moro et al., (2016) examined the effects TRF and a continuous diet during resistance training in healthy resistance-trained males. They found that TRF could decrease fat mass more than a continuous diet, while both diet groups were able to maintain muscle mass and strength. The protein intake in this study was very comparable to what you might see in an athlete or person eating high protein (1.9g/kg/day PRO). I did a whole week of infographics on TRF studies on IG if you want to see more data from them.

I would caution some interpretation in the studies above. I think they tell us that TRF can be used for a short time (8-10 weeks), but they don’t tell us about long-term changes. That said, for most people it won’t make a big difference, especially if it helps them adhere to the diet and meet their fat loss goals. On the other hand, I think an 8-10 week diet is a good time frame for those who don’t need to lose a lot of weight. If you need to diet longer than that you may want to include diet breaks or refeeds.

TRF is sounding pretty good right about now. Let’s get back to the study at hand.

Something should catch your eye. The amount of lean mass lost by both TRF groups. That makes me question their protein intake since protein seems to reduce lean mass losses. Surprisingly the authors didn’t report any macronutrient or calorie data though they do mention that the TRF groups “both regimens reduced daily energy intake by ~550 kcal/day.” I bet they publish that in a follow-up study since there are a whopping 18 secondary outcomes in the trial registration. Until that data comes out I’ll hold my judgment on this study.

How can we apply this?

It appears, based on a number of studies, that TRF is a viable option for weight loss. So, if you’re a coach go ahead and put it in your toolbox. It’s no magic pill, but it will definitely work as well as any other diet for some people.

What’s next?

We still have a lot of research to figure out if there are metabolic benefits to using TRF. The evidence is pretty mixed right now. I didn’t cover any of it in this review. The big question in the field is if the metabolic effects are due to weight loss or are due to the fasting. I’d speculate that it’s both and to tease out the difference we’re going to need very big, very well designed studies. With the increase in research, we might just see those in the next few years.