The fear of gaining weight is real. People who have lost a large amount of weight think about it constantly. Others whose goal is to gain weight generally want it to be in the form of muscle mass to improve their physiques. We also want to enjoy ourselves, so there are trade-offs with gaining weight. We might have certain times of the year where we are more likely to gain weight like any holiday with an excuse for drinking and celebrating.

But, there might be a silver lining. What if the body has mechanisms to prevent weight gain? What if our metabolism changes to adapt to us eating more? That’s what I’m going to cover in this blog. The idea of how people’s metabolism and other factors can or cannot change when overeating (aka overfeeding).

Metabolic Phenotype

First, let’s define a few things.

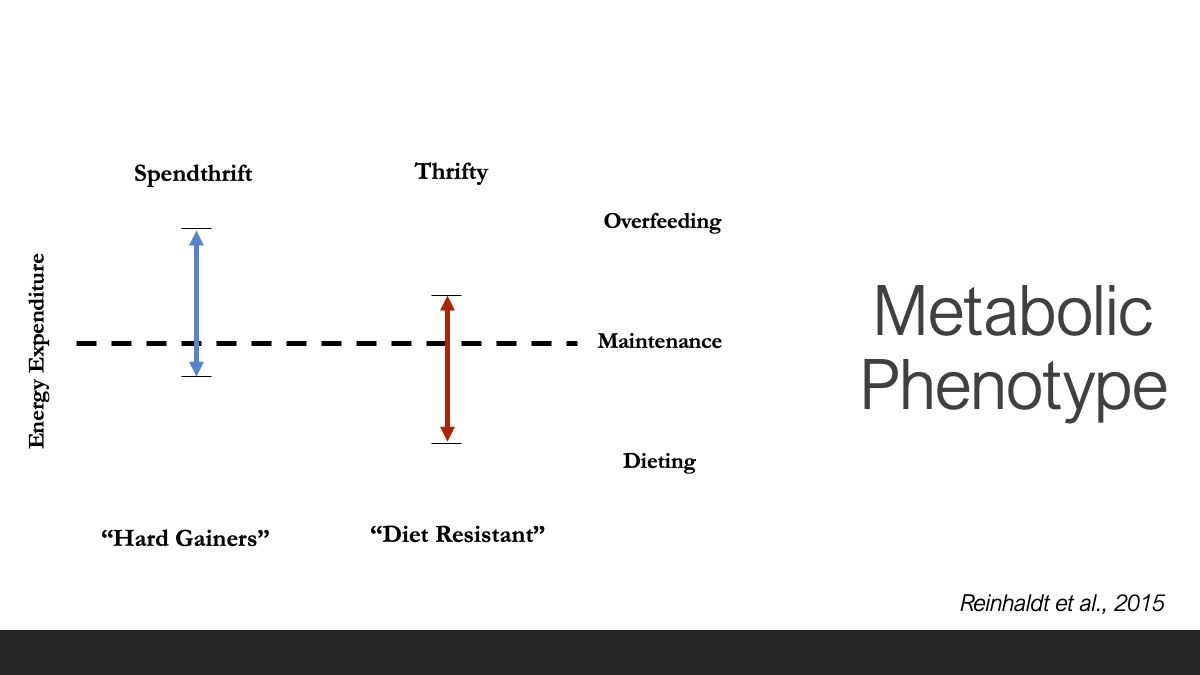

There are thought to be two metabolic phenotypes – Spendthrift and Thrifty.

A person who is thrifty will have a higher reduction in their metabolism with dieting, and a lower increase when overfeeding. This results in more weight gain when eating more, and less weight loss when dieting. We don’t want to be these people.

A person who is spendthrift will have a lower reduction in metabolism with dieting, and a higher increase when overfeeding. They tend to have a hard time gaining weight, but lose weight faster when dieting. We want to be these people.

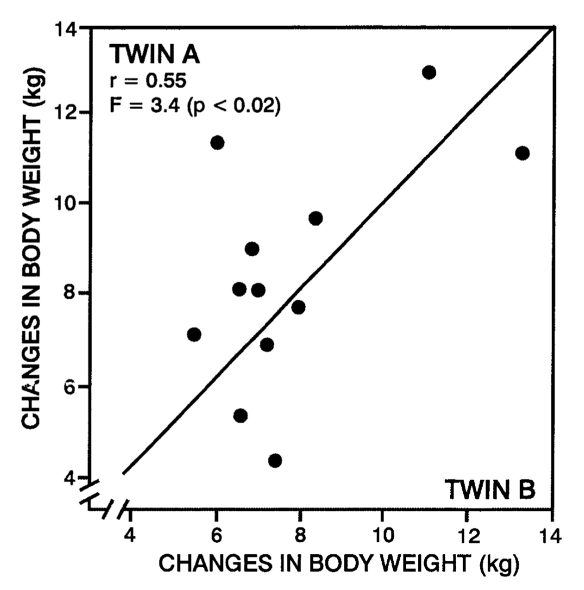

The problem is that we can’t choose which type of metabolism we have. We also don’t have any evidence that we can change it. It seems it is mostly genetically determined. A study on twins from the 1990s found that there was three times more variance in response between pairs of twins than within pairs of twins for the gains in body weight during overfeeding. The graph from Bouchard et al., demonstrates this elegantly. We see a strong correlation in twins who are overfed by 1000kcal per day for 100 days. The participants gained about 18lbs

on average, but the twins had a massive range between them, with the highest and lowest pairs having a ~10lb difference. This study was highly controlled, so all of the participants had the same environment and activity.

Thrifty or spendthrift metabolisms are one of those cool scientific discoveries that help us understand why some people can eat more than others and not gain weight, or why some people might struggle when dieting. Yet, in the end it doesn’t change how we approach nutrition. There are no special diets to make your metabolism faster or slower.

If genetics explains a portion of metabolic adaptations, what else happens when we overfeed? And how does it apply to what’s going on right now when we’re stuck at home?

There are some other studies that help guide us. Does it matter how long we’re overeating? Yes, it does.

Acute Overfeeding

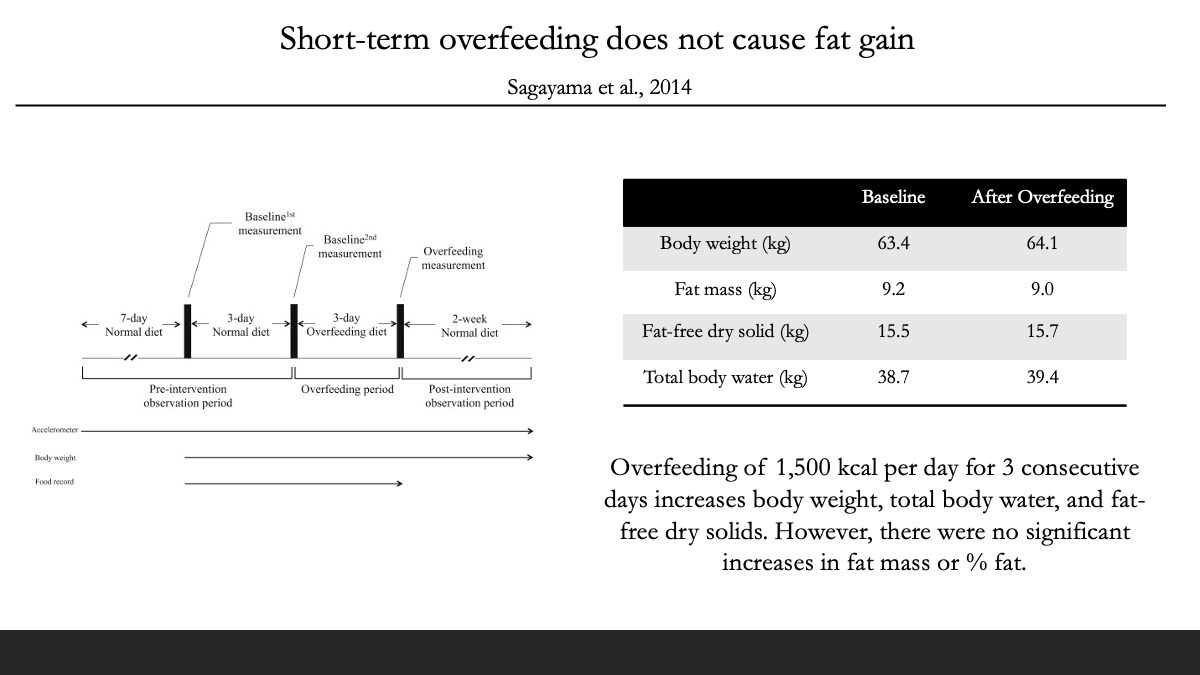

Overeating for a day or a long weekend doesn’t appear to matter much. If we do this every weekend then, of course, it’ll be detrimental in the long term. A study that illustrates this well is Sagayama et al., 2014. In this study they overfed participants 1500kcal per day for three consecutive days. That’s quite the surplus and would be akin to having a long weekend binge. In case you’re wondering, examples of what 1500kcals looks like at different restaurants can be found here. Ultimately, the study found that total body water was the main component that increased during overfeeding. There were no changes in fat mass or muscle mass. This tells us that it’s just water, so don’t be concerned if you overeat for a few days. If you’re someone who struggles with seeing the scale bounce upward after a weekend of overeating, then don’t use it for a few days – we don’t need to weigh every single day especially if it’s going to cause stress.

Long-term Overfeeding

The issue is when we overeat for more than a few days. There are plenty of studies that do this and we know what happens. We gain weight. Mostly fat too. How much weight though?

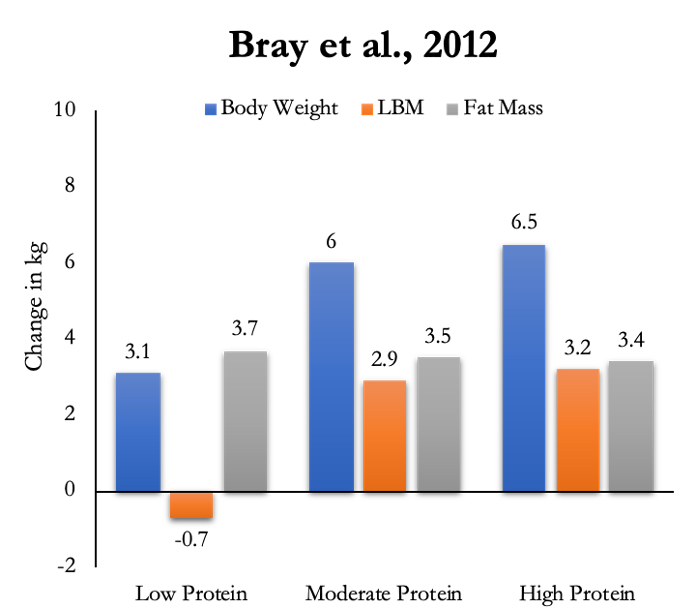

Let’s use another study as an example. In Bray et al., they overfed participants 40% for eight weeks. That’s still a lot. For example, for the 2000kcal diet that’s 800kcal extra per day. After 8 weeks the range of weight gain was 6-15lbs. Like the Bouchard study above, there was a lot of variance between participants. I graphed the change in body composition and body weight from that study here.

There was something interesting that happened in this study. They found that on a low protein diet (5% of total calories), more than 90% of the extra energy was stored as fat. In comparison, with moderate protein (15% of calories) and high protein diets (25% of calories) only about 50% of the excess energy was stored as fat. This tells us that we might want to have a high protein intake to avoid those extra calories being stored as fat. However, there was a caveat. The higher protein groups actually gained ~6lb of lean mass. I doubt this was muscle mass since they weren’t training. Importantly, all of the groups gained the same amount of fat. This was a very small study (5-6 people per group) so it’s hard to make out what really happened, but the changes in lean mass were probably due to water, food in the gut, and sodium.

When we overeat at home it might be in the form of snacks. They’re easy to access since the kitchen isn’t far. That, of course, could increase calories above normal. An interesting study was done by Claesson et al., where they had healthy, normal participants eat 20 kcal/kg/day of candy or roasted/salted peanuts in addition to their regular diet for two weeks. As an example, a 125lb female would be eating about ~1000kcal on this diet. That’s a lot but not too unreasonable when mindlessly munching on candy or snacks while working. After two weeks in the study, the authors found that only the group eating candy increased body weight by ~2lb, of which 38% was fat mass. The peanut groups experienced a non-significant increase in body weight of ~0.75lbs, all of which was fat free mass. This data tells us that the type of snack matters. In fact, other research has shown that adding peanuts into the diet results in a lower intake of other foods and increase in energy expenditure as well inducing satiety. I’m not saying you should have a bowl of peanuts next to your desk. I’m saying that if you do snack, choose something that is more filling and nutritious than candy.

Overfeeding & Activity

There is a silver lining to overfeeding. It might cause us to increase our non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT). NEAT is everything we do that isn’t sleeping, eating, or exercise. In fact, one study found that those who ate a 1000kcal surplus for 8 weeks dissipated 531kcal per day of the excess energy by an increase in energy expenditure, with most of that coming from NEAT. To add, changes in NEAT directly predicted resistance to fat gain with overfeeding and was not influenced by baseline body weight. So if we overeat and move more we can cancel out some of the effects of overfeeding.

There’s only one problem. What if we’re not able to move much? Like in a quarantine. This would negate the NEAT effects. That could be a problem, so it’s important to find a way to move no matter what the situation is – whether that’s through urban walks or hikes or bicycling around town. We have to find a way to make up for the increase in food intake if we can.

Summary

All of this science is great – isn’t it? It tells us that some people might gain more weight than others due to metabolic phenotype, there might be benefits to eating high satiety meals or snacks (with protein) and that we might even move more to compensate for the increase in food intake. We also learned not to worry about short-term overeating, but instead to think about how it affects your long term goals

Here are some practical ideas to prevent gaining weight:

→ Don’t buy highly palatable foods. This one is pretty simple. If you know that you’re prone to overeat chips or chocolate simply don’t buy them. Set your environment up for success.

→ Move more. Go on walks, get outdoors, pace your apartment, or go up and down the stairs in your apartment complex. This takes some conscious effort and is a little harder than not buying food.

→ Meal plan. Some people might stop meal prepping because their schedules change. That’s not setting yourself up for success. Keep as many of your old habits – like meal prepping – as you can.

→ Put on real clothes. Don’t lounge around in your sweats. Put those “hell no” pants on that you keep in the back of your closet and can only wear when you’re lean.

→ Get some data. Weigh in a few times a week. Track your macros. These are all things you might do anyway, so there’s no reason to stop now.