Our bodies are remarkable at adapting to different stimuli that we can then manipulate to produce different results. This allows us to set goals for ourselves and create lasting change.

We want to be healthier, leaner, stronger, faster. We want to age gracefully. We have aesthetic goals. We have performance goals. We want to feel better in our bodies. We want a healthier relationship to food.

We’re done with the extreme diets for weight loss only to gain it all back and then some. We’re done feeling like we’re dedicating so much time in the gym and not seeing proof of our hard work.

This blog will discuss another way we can go about accomplishing our goals that may apply to you.

You’ve heard us say this time and again, to produce noticeable changes in your body, the basic principle still stands: calories in vs. calories out (also known as energy in/energy out). For fat loss, calories in must be lower than calories out.

On the flip side, calories must be adequate in order to build lean muscle but not so much that we also add on unwanted body fat. Training needs to be dialed in for both in order to provide the body the stimulus to preserve our lean body mass (muscle, bone, etc.), strengthen it, and build more of it.

But what if there was a way to optimize the “balance” between the two by boosting both energy in AND energy out?

The “eat less, move more” mentality for fat loss isn’t completely wrong but it does raise the question: then what? You can eat less and move more for a period of time (like in a fat loss phase) but you can’t continue down that road forever.

For one, you’ll eventually hit a wall where you can’t exactly reduce your calories more or increase your activity level without risking health complications or injury.

Second, a constant reduction in calories, an attempt to eat less, can tend to generate a mentality of fear and apprehension about increasing the amount of food needed post dieting.

We see so many clients coming to us chronically under-eating, seeing a plateau in their weight loss efforts, losing motivation to continue eating less and exercising more, and experiencing higher cravings, food obsession, and a poor relationship to food and their bodies.

Enter G-flux or this idea of “eat MORE, move more”.

What if you could strategically increase your calories while following a structured training program and not only see the aesthetic results you’re looking for but optimize your performance and health markers at the same time? Too good to be true? Let’s find out…

What is G-flux?

G-flux, also known as energy flux, looks at the balance between energy in, energy out, and the rate at which energy is stored or the total energy turnover (1,2,4,5). Total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) is made up of your resting metabolic rate (RMR), the thermic effect of food (TEF), exercise activity thermogenesis (EAT) and non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT). All of these contributors play a role when you’re looking to increase your G-flux.

Your nutrition, training, daily activity, lifestyle factors, habits and behaviors, and body mass all play a role in whether your G-flux is high or low.

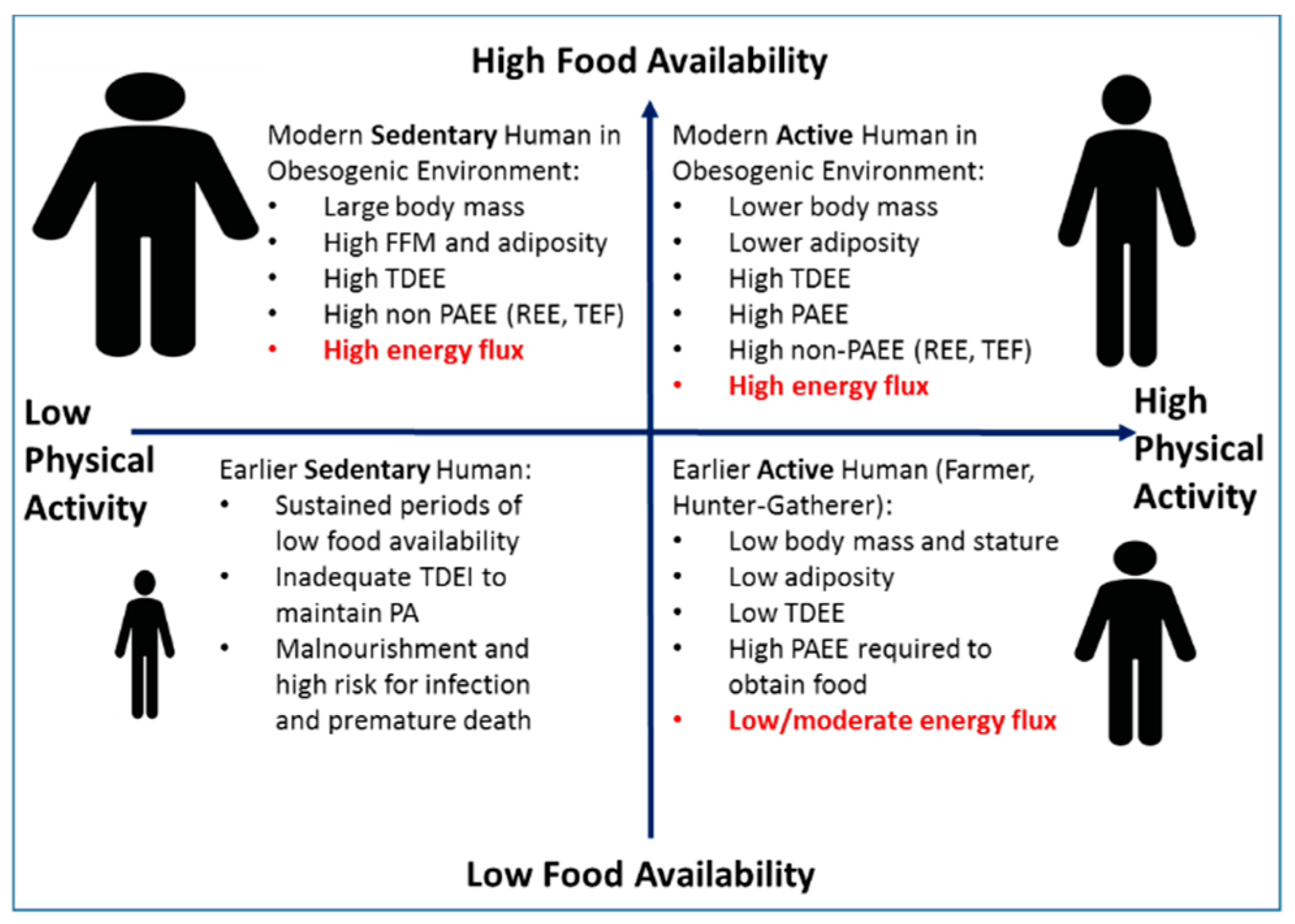

A high G-flux doesn’t necessarily equate to higher levels of health and fitness. We can see high G-flux in people who lead sedentary lifestyles and have a high body mass (as typically seen with obese individuals) because their RMR is high. At the same time, individuals who are highly active and with leaner body mass exhibit similar levels of high G-flux because of the larger contributions of their total physical activity (both EAT and NEAT) (4).

High G-flux means energy balance is achieved through high energy intake and energy expenditure, irrespective of total body mass. It’s important to note that increasing energy intake and output in order to increase G-flux doesn’t need to happen in congruence with each other. You can manipulate the variables independently based on your goals and starting point – more on that later.

Inversely, low G-flux occurs with reduced energy intake and expenditure, as often seen with weight loss. Maintaining weight loss is where most people face the biggest challenge. Even if you succeed in reversing your calories back up to your new maintenance level without regaining body fat, because you have less total body mass, your new maintenance calorie requirement is lower than before the diet.

When you combine our obesigenic environment of highly palatable, convenient foods with the fact that hunger and appetite are often higher upon completing a fat loss phase and/or if fat free mass has been lost during a diet (4), sustainable weight loss becomes an uphill battle.

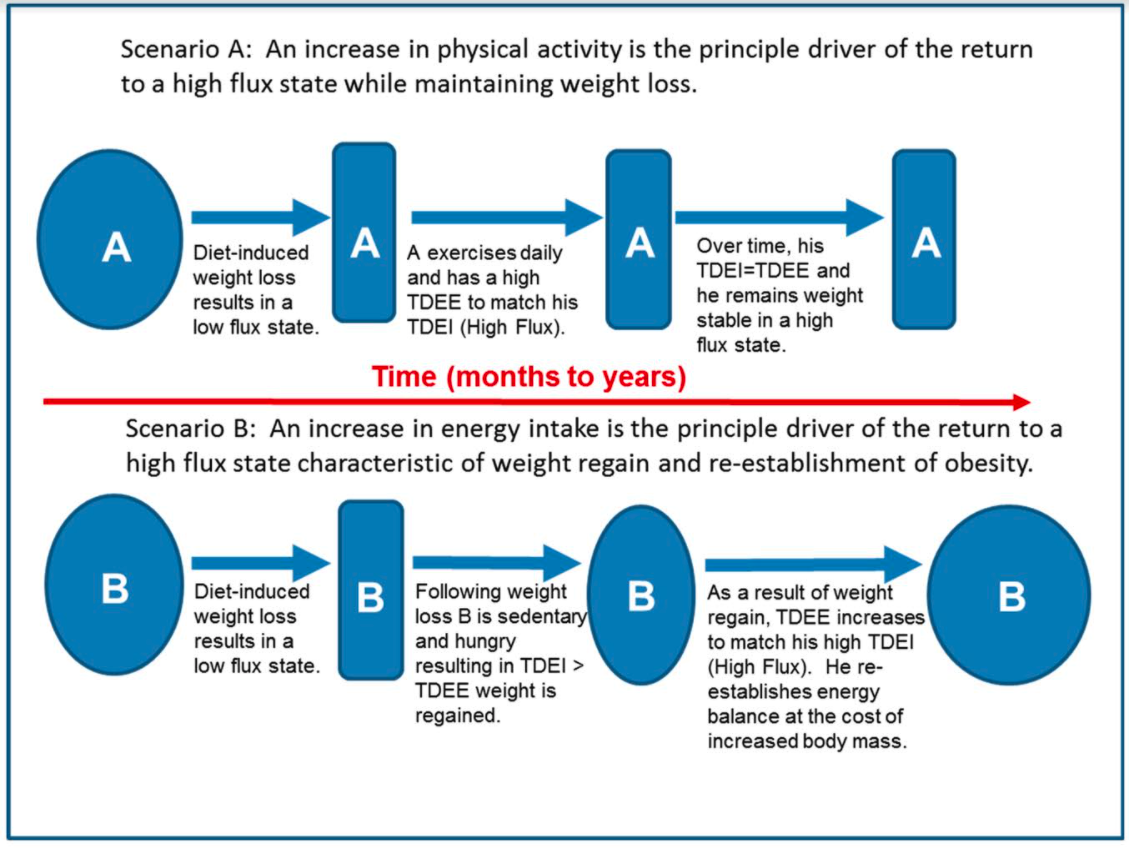

This essentially means that living in a low energy flux state isn’t sustainable – there’s a high probability that energy intake will increase following weight loss and, if energy expenditure (from EAT and NEAT) doesn’t also go up, it’s only inevitable that fat regain will occur.

On the other hand, maintaining a low intake to match lower activity levels results in a slower metabolic rate, loss of muscle mass, and a reduced capacity to use nutrients effectively – our overall health declines and we aren’t happy with our appearance either.

By focusing on increasing G-flux, we can maintain weight loss progress, increase lean mass, and improve performance and overall health in a sustainable way.

Benefits of G-flux

When G-flux is high, we see benefits across the board (1):

- Improved insulin sensitivity

- Greater ability to maintain weight loss after a diet

- Increased lean mass (muscle), decreased fat mass

- Improved appetite regulation

- Increased metabolic rate

- Better recovery

- Improved health

- Increased sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity

- Improved nutrient partitioning (how your body makes use of the nutrients from your food)

- Improved micronutrient delivery (ensuring vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients are delivered to the right places)

Who does G-flux apply to?

When we’re talking about changing body composition (fat loss and muscle gain) and improving overall health, the “eat more, move more” theory certainly has benefits that the standard “eat less, move more” concept of typical fat loss phases don’t. It’s important to note, however, that the G-flux model doesn’t apply to everyone but it can have a place within the nutrition periodization model that we use with the majority of our clients.

People who would greatly benefit from applying G-flux to their plan:

- You’ve reached your weight loss goal in your cut and are preparing to start your reverse diet, transitioning to maintenance or a lean gain phase. This places greater importance on the exercise part of the equation since a reverse diet already incorporates a gradual increase in calories. By increasing your physical activity during your transition to the next phase, you’ll be better able to maintain your weight loss, your body will utilize the incoming calories more effectively for health and support lean muscle growth, and you’ll improve appetite regulation (4).

- You’re looking for body composition changes and are currently at a relatively lean starting place. Body recomposition takes a lot of time and patience, but doing a targeted fat loss phase and/or a lean gain phase isn’t right for everyone. If you don’t have a lot of weight to lose but would like to lean out slightly, improve your training performance and recovery, and maintain or improve your overall health, creating a higher G-flux would be the way to go.

- You’re moving into a lean gain phase and want to minimize fat gain. Both food quality and training will play significant roles in the results of this phase. By emphasizing nutrient-dense foods and following a well-designed program along with regular low-intensity activity, you can optimize your muscle-building potential without accruing unwanted body fat.

- You’re a high-performing athlete who benefits from improved body composition but can’t afford to sacrifice your performance in the process.

Let’s take a look at each part of the “eat more, move more” equation.

Eating More

For starters, eating more doesn’t automatically mean hitting up the buffet or loading up on your favorite packaged snacks. The importance of nutrient-dense whole foods remains high, so continue incorporating plenty of fruits and vegetables, Omega-3 fats, and lean proteins.

Other critical components include establishing a proper balance of macronutrients (protein, carbohydrates, and fat), and having a structure to your meal timing. This not only supports better overall nutritional status, but plays a significant role in digestion, cravings, energy, mood, sleep, and appetite (3). Not to mention helping you perform better and recover from your daily activity and training, which is higher now as well.

Looking closer at protein in particular, maintaining a higher protein intake can contribute to a higher G-flux and weight maintenance. As mentioned above, one contributor to total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) is the thermic effect of food (TEF), or the energy required by the body to digest and absorb food. Protein has the highest TEF of the three macronutrients and is the most satiating. TEF will also increase from an overall increase in calories (4,6).

Total calories coming in will determine absolute energy intake, but we can’t ignore the importance of what those calories are made up of (macronutrients and micronutrients) and the quality of those calories (whole foods vs processed foods). Paying attention to your macronutrient distribution and overall food quality impacts what your body uses the food for and how effectively it’s able to do so.

[If you want help understanding how your macros AND micros should look… click here to download our free nutrition guide, The Tailored Nutrition Method: The All Inclusive Guide To Mastering Your Diet]

Moving More

Similar to eating more, moving more doesn’t equate to overdoing it on the exercise front. Following a progressive and thoughtful training plan, incorporating a variety of modalities, and including non-exercise activities (like walking) are all important factors to consider. Increasing exercise in general results in improved metabolic function, insulin sensitivity, appetite regulation, protein turnover, tissue remodeling, and nutrient partitioning (1,3,4). That means that, by increasing both quality food and exercise appropriately, the body is stimulated to use the calories for tissue building and repair resulting in more lean mass and less fat mass.

It must be emphasized that it’s recommended to increase exercise through a variety of modalities. Overtraining occurs when we over-stress one system, not necessarily from exercising a lot. There is a level of importance placed on strength training to support increasing lean tissue, however, overall health benefits of regular exercise are still seen with endurance training as well (4). Ideally, your training would include strength training that incorporates both max effort (strength) and dynamic effort (power), conditioning and/or high intensity work (sprints, intervals), and low-intensity movements (walking, yoga, biking) (2,3).

Establishing the appropriate balance for you will depend on your goals, training age, and recovery. If you’re not already exercising a total of five hours per week, start there by following a well-designed training plan and including regular non-exercise activity (for our app with daily workouts, check out The Tailored Trainer).

Application & Adjustments for your goals

Once you’ve dialed in the nutrition fundamentals and are including at least five hours per week of regular physical activity, you can now make slight adjustments to maximize your goals.

- Fat loss: gradually increase your activity closer to eight hours per week coming from both higher intensity and recovery modalities. Again, ensure that your weekly activity remains balanced and progressive. At this point, keep your calorie intake the same.

- Muscle gain: increase your calories slightly (~10% to start) while keeping your weekly activity to 5-6 hours per week.

Potential drawbacks

While the G-flux model sounds pretty damn good, it is important to discuss some potential drawbacks to the model and why it may not be the best route for you (or at least not right now).

- You have a significant amount of body fat to lose and going into a deficit makes more sense to start with.

- You’re not at a consistent place with your nutrition and/or exercise – attempting to increase your intake and dedicate time to following a program if you’re not yet consistently eating nutrient-dense, whole foods and including daily activity into your week is like trying to build a house on a shaky foundation. Don’t underestimate the basics.

- You have an unhealthy relationship to food and/or exercise. For some, eating more food improves appetite regulation, decreases cravings, and improves their mindset around food. For others, it’s a mental hurdle that they haven’t yet worked through and consistently eating enough needs to be addressed first. Similarly, increasing exercise can dramatically increase someone’s mental and physical well-being and how they view and take care of themselves. For others, increasing exercise is a slippery slope to a “more is better” mentality that may result in over-stressing one system (i.e. overtraining) or using exercise in an unhealthy way.

Conclusion

If you’re seeking body composition changes, it may come as a comfort to you that implementing a fat loss phase (a deficit) isn’t the only way to achieve your goals.

Similarly, if you have completed a recent deficit, you can successfully increase your G-flux by increasing your physical activity while simultaneously increasing your calories without body fat regain.

Implementing the G-flux model into your plan can provide major benefits to your fat loss goals, muscle building goals, and ability to reverse from a fat loss phase sustainably.

Through this concept, your metabolic rate also increases, allowing you to better utilize the nutrients coming in which means improving your overall health status, training performance, and recovery.

References:

- Andrews, M. R. S. (2020, August 4). All About G-Flux. Precision Nutrition. https://www.precisionnutrition.com/all-about-g-flux

- Berardi, N. J. T. (2006). G-Flux | T Nation. T NATION. https://www.t-nation.com/diet-fat-loss/g-flux

- Shugart, N. C. T. (2008). G-Flux Redux | T Nation. T NATION. https://www.t-nation.com/diet-fat-loss/g-flux-redux

- Melby, C. L. (2019). Increasing Energy Flux to Maintain Diet-Induced Weight Loss. MDPI. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/10/2533/htm

- Hull, M. (2021, March 3). Thermic Effect of Food. Examine.Com. https://examine.com/topics/thermic-effect-of-food/